Private Property and Government Inaction

Like a driver who is obligated to use his brakes to prevent hitting a pedestrian in a road, governments have a duty to protect private property with the right laws and regulations, says a Vanderbilt Law School professor. And if a governmental body fails to do that, then property owners should be able to get relief under the Constitution.

“In some contexts, government inaction is the most costly choice for all of society,” says Christopher Serkin, professor of law. “Where that is true, forcing the government to pay for its regulatory acts but not its omissions will have the perverse consequence of deterring the government from doing anything at all, even if a regulatory response could increase overall societal well-being dramatically.”

Serkin sets out his viewpoint in an upcoming paper to be published by the Michigan Law Review. Typically, the Constitution is thought to create negative rights—those that constrain the government from acting in certain proscribed ways. Saying that governments can be legally liable for failing to act is a huge step.

Serkin argues his point through the example of rising sea levels affecting property owners, but believes the concept could apply in settings as far-reaching as copyright law and financial regulation.

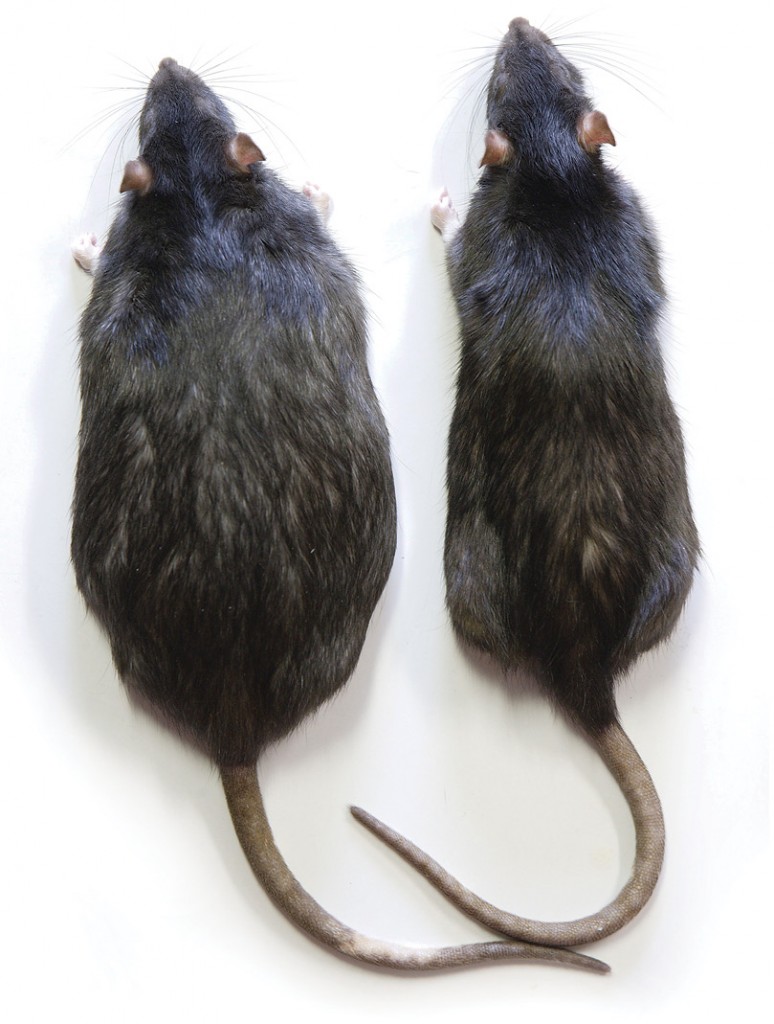

Probiotic Could Prevent Obesity

Bacteria that produce a therapeutic compound in the gut inhibit weight gain, insulin resistance and other adverse effects of a high-fat diet in mice, Vanderbilt investigators have discovered.

“Of course, it’s hard to speculate from mouse to human,” says senior investigator Sean Davies, assistant professor of pharmacology. “But essentially, we’ve prevented most of the negative consequences of obesity in mice, even though they’re eating a high-fat diet.”

Regulatory issues must be addressed before moving to human studies, Davies says, but the findings published in the August issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation suggest that it may be possible to manipulate the bacterial residents of the gut—the gut microbiota—to treat obesity and other chronic diseases.

Freedom from Power Cords

Imagine a future in which our electrical gadgets are no longer limited by plugs and external power sources. This intriguing prospect is one of the reasons for the current interest in building capacity to store electrical energy directly into a wide range of products, such as a laptop whose casing serves as its battery, or an electric car powered by energy stored in its chassis, or a home where the drywall and siding store electricity that runs the lights and appliances.

It makes the small, dull-gray wafers that graduate student Andrew Westover and Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering Cary Pint have made in Vanderbilt’s Nanomaterials and Energy Devices Laboratory far more important than their nondescript appearance suggests.

The new device is a supercapacitor that stores electricity by assembling electrically charged ions on the surface of a porous material, instead of storing it in chemical reactions the way batteries do. As a result, supercaps can charge and discharge in minutes instead of hours, and operate for millions of cycles instead of thousands of cycles like batteries.

“These devices demonstrate—for the first time, as far as we can tell—that it is possible to create materials that can store and discharge significant amounts of electricity while they are subject to realistic static loads and dynamic forces, such as vibrations or impacts,” says Pint.

Details appeared online May 19 in the journal Nano Letters.

Pickiness Doesn’t Always Pay

Cougars may have survived the mass extinction that took place about 12,000 years ago because they were not as finicky as their cousins, the saber-toothed cat and American lion. Both perished along with the woolly mammoth and many other supersized mammals during the Late Pleistocene age.

That is the conclusion of a new analysis of the microscopic wear marks on the teeth of cougars, saber-toothed cats and American lions described in the April 23 issue of the journal Biology Letters.

“Before the Late Pleistocene extinction, six species of large cats roamed the plains and forests of North America. Only two—the cougar and jaguar—survived,” says Larisa R.G. DeSantis, assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences at Vanderbilt, who co-authored the study with Ryan Haupt at the University of Wyoming.

Researchers analyzed teeth of 50 fossil and modern cougars, and compared them with teeth of saber-toothed cats and American lions excavated from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles and the teeth of modern African carnivores including cheetahs, lions and hyenas.

Among the La Brea cougars, the researchers found significantly greater variation among individuals than in the other large cats, including saber-toothed cats. “This suggests that the Pleistocene cougars had a ‘more generalized’ dietary behavior,” says DeSantis. “Specifically, they likely killed and often fully consumed their prey, more so than the large cats that went extinct.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Learn more about cougar appetites: