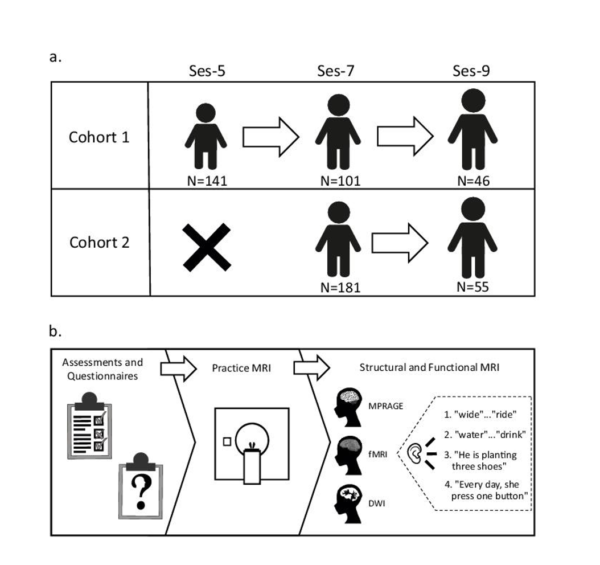

A new comprehensive data set featuring neural images from children ages 5, 7 and 9 has been made available for cross-disciplinary research purposes. Led by James Booth, Patricia and Rodes Hart Professor of Educational Neuroscience in the Department of Psychology and Human Development at Vanderbilt, the brain imaging initiative includes structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging, as well as extensive psychoeducational assessments and in-depth parental questionnaires. The MRI component is unique because it uses multiple tasks that tap into various aspects of language at the word and sentence level (see Figure for an overview of the project).

“The data set can be used by a wide variety of research disciplines including education and psychology, as well as developmental and learning sciences,” Booth said. “It is our hope that this data can lead to significant new discoveries by researchers working on solving important problems in language acquisition and disorders.” Booth and his team have published some work on this data, but much remains to be investigated.

Booth explains that the large scale and scope of this data set are unique. The data includes neural images from more than 300 children and provides unique data because each individual has multiple time points. “A lot of the neuroimaging projects are cross-sectional and only provide a snapshot of the brain in children of different ages. But, the longitudinal approach to this study allows researchers to make causal inferences about what drives brain development.”

This new data set is in addition to several others shared by the Brain Development Laboratory that examine reading, math and attention in typically developing children and those with learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. This brings the total of participants to more than 1,000 and the number of individual scans to almost 12,000. Booth is one of the leaders in the movement to make data public, which is becoming critical in education and psychology. It allows the results to be reproduced and new work to replicate previous studies. It also allows raw data sets to be combined to allow for even bigger science.

Booth further explains that the data set offers strong potential for clinical breakthroughs. “Typically, the study of the way children learn has relied on behavioral predictors of future problems. By analyzing neural images, we can better understand the biological predictors of learning. Eventually this information should be able to identify learning issues early so that intervention can be applied early in development.”

Booth says that researchers across disciplines have already begun to use the data to support key studies, so he is hopeful that this will lead to new collaborations. Researchers at the University of Buffalo have used the data to analyze reading development in children. International researchers from Nigeria and Malaysia have used the data to explore early markers for dyslexia. “It is my hope that this data can continue to be used by researchers across the globe to support advances in their fields.”

The neural imaging collection project was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. “I’ve been supported generously by the NIH in the past, so I feel that it is my duty to make this data available for further research,” Booth said. The data set is available on OpenNeuro, a free and open platform for sharing neurological data. This data set has recently been described in a paper in the journal Scientific Data.

“It is a huge endeavor to share the data but is definitely worth it,” said Jin Wang, who took the lead in organizing and uploading this dataset. “Sharing the data will not only benefit global researchers, but it also embraces open science and aids in reproducibility, reliability and the impact of neuroimaging research.”

Additional contributors to the neural imaging data set include Brianna Yamasaki, postdoctoral fellow in psychological sciences at Vanderbilt; Marisa Lytle, graduate student in psychological sciences at Penn State University; and Yael Weiss-Zruya, postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences at the University of Washington.