By Jenna Somers

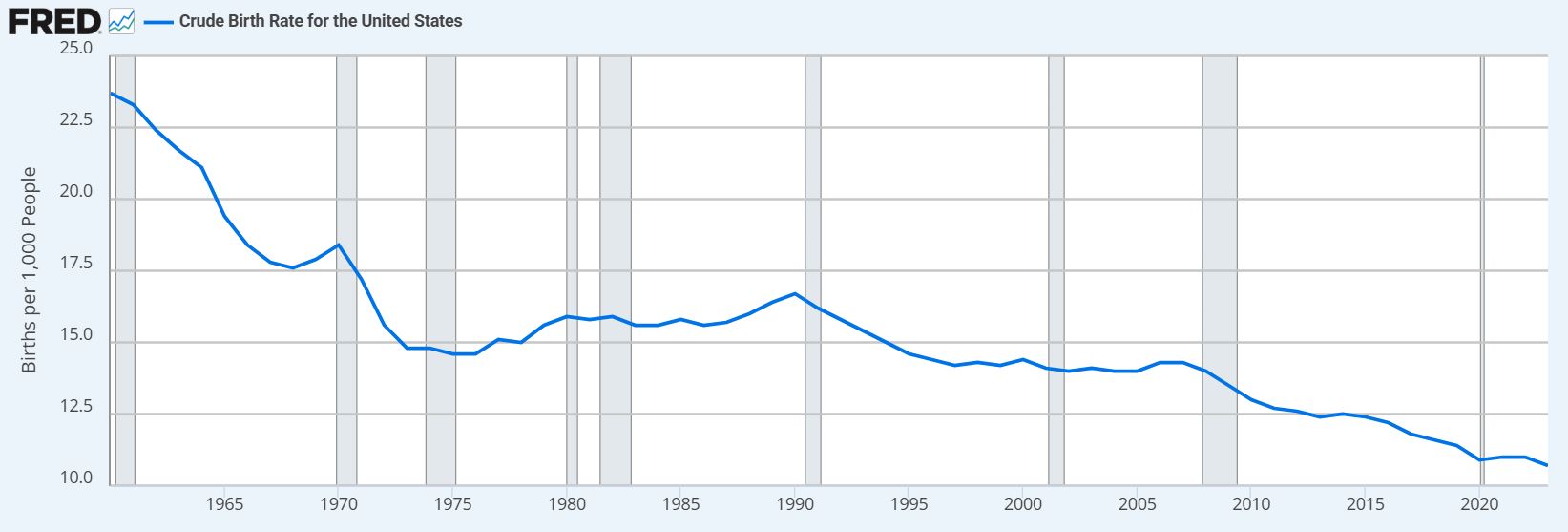

The Great Recession of 2008 led to a pronounced decline in birthrates, and the impact has caught up with colleges and universities. Children born at the start of the recession are now 18 years old, but there are fewer of them compared to the prior decade, likely leading to fewer students matriculating to college. Moreover, birthrates have continued to fall since the Great Recession, meaning the decline is not a short-term problem for higher education.

A shrinking population of traditional college-aged students and a decade of growing concerns about the value of higher education requires that colleges and universities adapt to the needs of students, from recent high school graduates to adult learners. That’s according to Will Doyle, Brent Evans, and Emily House, scholars at Vanderbilt Peabody College of education and human development.

“Fluctuations in the proportion of the population ages 18 to 24 are very important to colleges and universities,” said Doyle, professor of public policy and higher education. “This population increased in the early 2000s until about 2015 to 2017, which meant that selective institutions had a bigger group from which they could select students. Less selective institutions had more people who wanted to attend, so most institutions did well. They could rely on people willing to pay the prices they were charged. It was essentially a seller’s market from the perspective of colleges and universities. Now the situation is flipped.”

“‘It was essentially a seller’s market from the perspective of colleges and universities. Now the situation is flipped.’”

Institutional variability

Depending on institutions’ selectivity, financial circumstances, and sensitivity to labor market trends, the effects of demographic decline vary. Selective institutions might need to admit more students to yield desired freshmen class sizes. However, less selective, smaller colleges that have always had relatively low enrollments and are heavily tuition-dependent are showing signs of financial stress.

“Some are seeking to merge with other small colleges or are getting bought up by for-profit institutions,” said Evans, associate professor of public policy and higher education. “Small colleges that are almost one hundred percent tuition-revenue driven are most likely to see the biggest impacts because as there are fewer students and fewer students want to go to college, the value proposition of paying full price is lower.”

He added that some public universities are constrained by state policies or agreements with their states that require a certain percentage of each incoming class to be state residents. This means that schools in states with the worst demographic decline, such as those in the Northeast, may be in a greater financial bind.

Community colleges also have unique concerns. They typically serve more adult learners than traditional-aged college students, but as Doyle and Evans note, they are sensitive to labor market trends and are not entirely immune to demographic decline.

On the one hand, in a good labor market with high employment, fewer adult learners typically return to school to obtain degrees or technical training certificates. On the other hand, demographic decline could reduce the number of students in the transfer-student pipeline. These are traditional college-aged students who decide to complete their first two years at community colleges and then transfer to a four-year university.

Due to a shrinking population of 18-to-24-year-olds and selective institutions possibly admitting more students to yield desired class sizes, community colleges might attract fewer of these students, which could create financial hardships for these institutions.

Communicating higher education’s value

“Higher education institutions need to be very strategic about communicating their value,” said House, lecturer of leadership, policy and organizations, and the former executive director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. “Not only is the demographic shift happening, but people are questioning, rightly or wrongly, what is higher education’s value? So, it’s important to develop messaging around the financial and societal benefits and being explicit about those.”

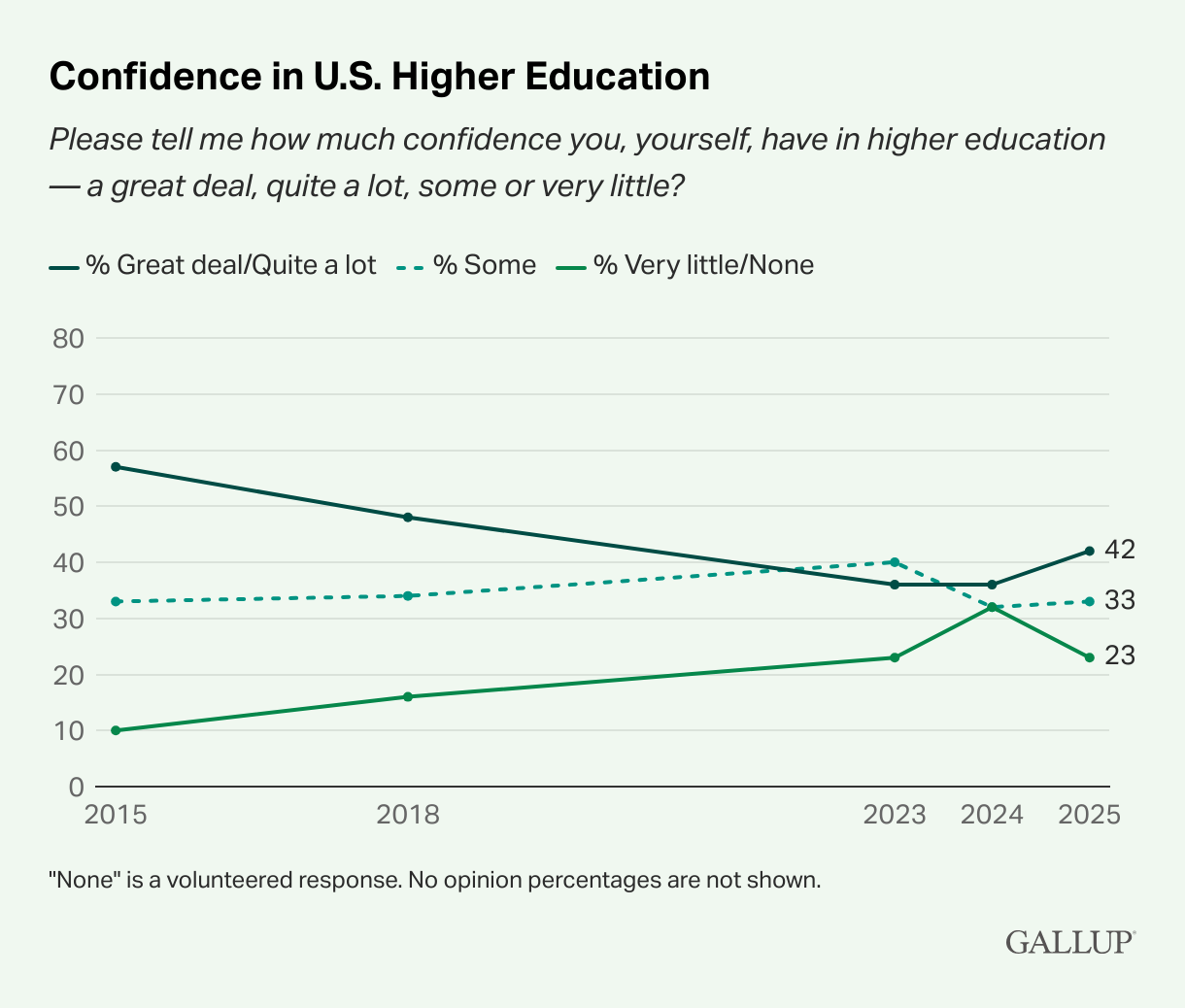

While Americans have doubted in recent years whether a college education still confers value, results from 2025 surveys by Gallup and the Lumina Foundation and New America show an uptick in Americans’ confidence in higher education, with Gallup showing an increase from 36 percent in 2024 to 42 percent in 2025.

Research also continues to demonstrate that a college degree leads to substantial financial gains over one’s lifetime and correlates with better health outcomes, greater civic engagement, and other non-financial benefits to individuals and society.

Research also continues to demonstrate that a college degree leads to substantial financial gains over one’s lifetime and correlates with better health outcomes, greater civic engagement, and other non-financial benefits to individuals and society.

Even with these benefits, prospective students worry about affording a college education. Evans’ research has demonstrated that various complexities associated with student loans contribute to many students’ aversion to borrowing for college. House says that institutions might want to emphasize long-term financial returns in their messaging to prospective students. “Someone may not see significant gains in the first five years after earning a bachelor’s degree, but they will probably make a lot more in 20 years than if they didn’t have one,” House said.

Institutions also need to consider how to align their messages with the concerns of specific communities who may feel alienated from higher education. House and Evans say that recent survey data indicates that the politicization of higher education factors into perceptions about its value.

In the 2025 New America survey, 56 percent of Americans believe colleges are more welcoming of politically liberal views. In Gallup’s 2024 data, of Americans who lack confidence in higher education, 41 percent see colleges as “too liberal.”

To address these concerns, House suggests that institutions focus their messaging on financial aid for students and the long-term financial benefits of a college education.

Meeting students’ needs

Increasingly, prospective students want flexible course schedules and modalities as well as a quicker path to a workforce-aligned credential, such as a certificate. “We have to think about making higher education work for students in a way that may not have been top of mind before, so things like online courses, workforce-aligned credentials—these ideas have now grown in the face of shifting enrollment and concerns about the value of higher education,” House said.

To meet the evolving needs of students, Peabody College began offering graduate and professional certificate programs last year, as well as a post-master’s degree online certificate in Applied Behavioral Analysis. These certificate programs give graduates a competitive edge to respond to urgent and emerging priorities in education and human development.

Peabody also offers an online education doctorate in Leadership and Learning in Organizations for mid- and senior-career professionals who drive systemic improvements within their workplaces across various industries. The program was ranked No. 1 in the nation in 2024 by Fortune magazine.

Offering programs responsive to students’ needs is one part of the puzzle for tackling the challenge of demographic decline; the other is student recruitment.

“There is an increased effort among enrollment managers to drum up more applications,” Evans said. “They’re trying to figure out where they can get more students. Public institutions, particularly in states experiencing larger demographic decline, may invest more resources in attracting out-of-state enrollments, especially institutions not constrained by policies regarding in-state residency percentages for incoming classes.”

Likewise, global outreach and recruitment has long been vital to U.S. universities. International students often pay full out-of-state tuition, which can help to lower costs for U.S. students and support other institutional priorities. During periods of demographic decline among domestic students, international student enrollment takes on additional importance to universities’ teaching and research missions.

Rapidly evolving federal policies on international student visas present recruitment and enrollment challenges. However, Shilpa Patwardhan, assistant dean and executive director of the Peabody Leadership Institute and interim enrollment manager at Peabody College, says U.S. higher education has an opportunity to innovate new programs. “We can expect offerings for online programs and non-traditional stackable credentials to increase at many universities,” Patwardhan said.

State impacts and the role of state policymakers

Demographic decline doesn’t just affect the finances of higher education institutions. The strength of state economies is downstream of a state’s college-educated workforce. According to Doyle, states are trying to attract more high-skill, high-earning jobs that demand a college education, which could lead policymakers to consider ways to increase access to post-secondary education for 18-to-24-year-olds and adult learners.

“Your working age population, ages 25 to 64, is hugely important for the overall health of the state economy. They drive the tax base, and therefore, all the things that the state can do. If you can project that in 10 years this population will shrink, fewer of them will have college degrees and be able to work in high-paying jobs, your state’s economy will probably be worse off. In particular, states with large demographic downturns can’t accept historic patterns of people either not going to college or not completing their degrees. Those problems become much more acute,” Doyle said.

As states grapple with the economic outcomes of a demographic decline among traditional college-aged students, they could look to increase their support for older adult learners to return to college. According to House, that is what Tennessee did. The state offers tuition assistance through the Tennessee Reconnect program, designed to help adults return to higher education or enroll for the first time to gain new skills and advance in their careers. Tennessee institutions developed online Adult Degree Completion Programs to offer working adults and parents the flexibility to return to the classroom.

“How can the funds that would typically support 18-year-olds in the form of grant aid be used to incentivize adult learners to enroll in workforce-aligned programs, or be used to help low-income students or people from rural communities gain access to higher education? These are the types of things policymakers might need to consider,” House said.

“’How can the funds that would typically support 18-year-olds in the form of grant aid be used to incentivize adult learners to enroll in workforce-aligned programs, or be used to help low-income students or people from rural communities gain access to higher education?'”

In response to concerns about the value of higher education, some policymakers have moved to implement accountability measures to ensure that college degrees lead to higher wages. House says Colorado was one of the first states to develop a measurement for accountability, known as the minimum value threshold, which is calculated by a student’s incremental earnings minus higher education costs.

House consulted with colleagues at the Colorado Department of Education as they developed this assessment. Their analysis found that 97 percent of bachelor’s degree programs met the minimum value threshold, meaning students were better off financially from having earned their degree. Across all assessed programs—certificates, associate’s, and bachelor’s degrees combined—86 percent of programs met the minimum value threshold.

Is past prologue?

Crude birth rate for the United States. Shaded areas indicate U.S. recessions.

In the 1980s, colleges and universities expected a similar enrollment cliff following a steady decline in birthrates that began in the 1960s. However, the exact opposite occurred. While there were fewer 18-24-year-olds, more of them wanted to go to college as America de-industrialized and transitioned to a knowledge economy. “Institutions were market savvy and flexible. They recruited people who otherwise may not have gone to college,” Doyle said.

The spread of AI may be ushering in another economic transition. Speculations abound about whether AI will replace jobs; if so, which ones? By replacing workers, will automation mitigate any possible negative effects on the economy associated with a shrinking population? These questions highlight known unknowns, but colleges and universities are keenly aware of the need to adapt programs, so that students are ready to enter an AI-driven workforce. If the past is prologue, could a demand for workers to upskill and reskill to thrive in an AI-based economy actually increase college enrollment in the coming years—just as the educational demands of a knowledge economy did in the 1980s?

“If the past is prologue, could a demand for workers to upskill and reskill to thrive in an AI-based economy actually increase college enrollment in the coming years…”

Only time will tell, so leaving aside that question, colleges and universities are preparing for the varied effects of demographic decline, with smaller, less selective, and tuition-dependent institutions facing the most difficult challenges in the coming years. However, the overarching need for colleges and universities to communicate their value and adapt to the evolving needs of students remains essential, as Doyle said, “During the last demographic downturn, colleges and universities got better at responding to student needs. This is another opportunity to do so, and I think that is a good thing. It’s about considering the needs of today’s students and putting together an experience for them that’s going to shape their future in a positive way.”