By Jenna Somers

Every year, an estimated 2.8 million Americans suffer a traumatic brain injury, and more than 5 million Americans live with a permanent brain injury-related disability. TBI-related disabilities can impair speech; cognitive, motor, and sensory functions; and lead to negative behavioral outcomes.

In two recent studies funded by the National Institutes of Health, moderate-severe TBI was associated with difficulties in communication, namely remembering spoken language and integrating information in gesture with speech. Both impairments can inhibit a person’s ability to understand and effectively communicate with others, but the research teams hope the studies’ findings could pave the way for improved therapies and assessments to help people with TBI communicate more easily in their daily lives.

Impaired memory for spoken language contexts

Published in Brain and Language, the study, “Temporary ambiguity and memory for the context of spoken language in adults with moderate-severe traumatic brain injury,” found that people with TBI may have difficulty recalling details of what someone said.

The study was led by Sarah Brown-Schmidt, professor of psychology and human development at Vanderbilt University Peabody College of education and human development, Kaitlin Lord, Ph.D. student at the University of California, Irvine, and Melissa Duff, professor of hearing and speech sciences at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

The researchers examined how adults with and without TBI processed slightly ambiguous or confusing spoken language. For example, participants viewed scenes with multiple images and heard a speaker refer to a “striped bag” or a “bag with stripes.” The phrasing is different, but the meaning is the same. Study participants with and without TBI managed these ambiguities well. They had a better memory for similar, though unmentioned items, such as a “dotted bag,” rather than inconsistent items, such as a “dotted tie.”

“This finding suggests that people with TBI can still remember relevant details from linguistic contexts—in this case the ‘dotted bag’—even if their overall memory for the discourse was impaired. After listening to a sentence, individuals with TBI successfully identified what items had been discussed, regardless of slight difference in phrasing,” Brown-Schmidt said.

However, a subsequent memory test demonstrated that these successes for those with TBI were in the context of overall weaker memory and less of a memory boost for the specific objects that had been discussed. This finding suggests that people with TBI may have a more impaired memory when later recalling linguistic contexts and topics than people without TBI.

Impaired speech-gesture integration

Published by Cortex, the study, “Reduced on-line speech gesture integration during multimodal language processing in adults with moderate-severe traumatic brain injury: Evidence from eye-tracking,” indicates that people with TBI may have greater difficulty integrating information from gesture with speech to predict upcoming words.

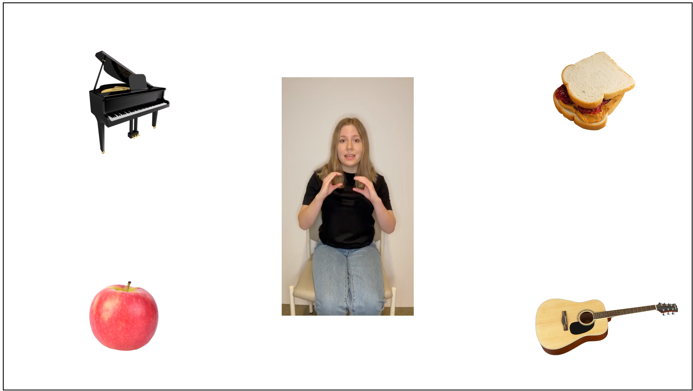

In this study, participants with TBI and non-injured peers watched videos of people speaking and gesturing. The videos were embedded in a visual scene with four pictures of everyday objects—a sandwich, apple, guitar, and piano—placed in the corners of the screen. In one example trial, the speaker says something like, “The girl will eat the very good sandwich.” When the speaker produced the verb phrase “will eat,” she simultaneously produced a gesture depicting holding a sandwich near the mouth. The research team used eye-tracking to examine how participants with and without TBI used information from gesture to predict upcoming words. For example, when non-injured participants saw the sandwich-holding gesture as they heard “will eat,” they looked to the picture of the sandwich even before the speaker said the word, “sandwich.” Participants with TBI also showed this effect, but it was significantly smaller in the TBI group.

“Communication is full of rich visual cues like gesture, facial expression, and eye gaze that influence language processing. Our finding suggests that when it comes to gesture, some people with TBI may have difficulty rapidly integrating visual information from gesture with the unfolding speech signal to understand the speaker’s message,” said Sharice Clough, PhD’23, postdoctoral research fellow in the Multimodal Language Department at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Gestures are a natural part of communications, so difficulty processing them could make it harder for listeners to follow a conversation and understand what others are saying in their daily lives.

In addition to Clough, Brown-Schmidt, and Duff, Sun-Joo Cho, professor of psychology and human development at Vanderbilt Peabody College, co-authored this study.