A collaborative team led by Piran Kidambi, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, William Fissell, associate professor of nephrology and hypertension at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Shuvo Roy, professor of bioengineering at University of California, San Francisco, and Francesco Fornasiero, biosciences and biotechnology staff scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Lab, has developed a new type of filter for kidney dialysis machines that can clean the blood more efficiently and improve patient care.

Chronic kidney disease, a condition where kidney damage results in poor blood filtration, affects approximately 697.5 million people—or 9 percent of the global population. Treatment includes hemofiltration, hemodialysis or kidney transplantation. Hemofiltration and hemodialysis support the kidneys by filtering toxins and waste products from blood.

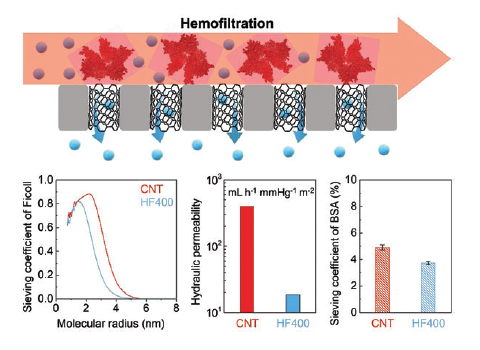

The new filter uses carbon nanotubes—tiny tubes formed by a sheet of carbon atoms bonded in a hexagonal honeycomb mesh structure—that have very small, smooth channels. These channels make it easier to remove toxins and waste from the blood without letting important proteins escape, which can be a problem with traditional filters.

In the article “High-Performance Hemofiltration via Molecular Sieving and Ultra-Low Friction in Carbon Nanotube Capillary Membranes,” published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials on Aug. 27, Kidambi and his co-authors demonstrate that their dialysis membranes made up of carbon nanotubes and polymers create a new paradigm for dialysis.

“Our membranes outperform state-of-the-art dialysis membranes by more than an order of magnitude while simultaneously allowing for enhanced removal of middle molecules that could cause toxicity and other health complications,” Kidambi said. “We showed that precise control of carbon nanotube diameters not only allowed for enhanced and effective removal of middle molecules, but the straight channel geometry as well as slippery walls of the nanotubes allowed for significantly enhanced flow.”

The work also yielded fundamental insights on how biomolecules transport in nanoscale constrictions. Like an octopus that can contort itself to fit in the smallest spaces and then expand, Kidami and his co-authors discovered that biomolecules squeeze into the entrance of the nanotube in the membrane, travel through it and expand again on the other side. This knowledge can help researchers and engineers design membranes for biological separations beyond dialysis.

Using better membranes in dialysis is beneficial for patient care. Kidambi and his colleagues plan to assess long-term operational feasibility, blood compatibility and other questions about the filter to develop it for patient care. They aim to further this technology with advances the Kidambi lab has made in graphene.

“Our goal is to enable smaller kits for dialysis so they can go to patients, instead of them coming to the hospital and getting strapped into a dialysis machine three times a week for four hours,” said Peifu Cheng, a postdoctoral research associate in the Kidambi lab and the paper’s first author. “That would be a huge improvement in the quality of life of the patient. Our long-term goal is to move toward implantable devices.”

The research was supported by faculty startup funds from Vanderbilt University and Kidambi’s NSF CAREER award. A portion of this work was performed at the Molecular Foundry, which was supported by the Offices of Science and of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy.