Research increasingly links the gut microbiome to a range of human maladies, including inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes and even cancer. Attempts to manipulate the gut with food rich in healthy bacteria, such as yogurt or kombucha, are in vogue, along with buying commercial probiotics that promise to improve users’ chances against illness.

Changing the gut microbiome to beat illness really does hold great potential, said Vanderbilt University biologist Seth Bordenstein, but first scientists must answer what constitutes a healthy gut microbiome and in whom. By studying data on nearly 1,700 Americans of varying genders, ages, weights and ethnicities, they learned that gut microbiome differences among ethnicities are the most consistent factor.

That discovery holds promise in the burgeoning field of individualized medicine, because it is far easier to change a person’s microbiome than their genes – the other major markers for disease. In addition, many chronic diseases disproportionately affect ethnic minorities, with underlying causes of that difference unexplained. Perhaps some answers lie in the gut microbiome.

“Human genomes are 99.9 percent the same between any two people, so what we’re really interested in is what explains the marked variations in gut microbiomes between people,” said Bordenstein, associate professor of biological sciences. “What are the rules, and can we manipulate that microbiome in order to improve health and medicine in the long run? If you look at common factors associated with gut microbiome differences, such as gender, weight or age, you find many inconsistencies in the types of gut bacteria present. But when we compare differences by patients’ self-declared ethnicities, we find stable and consistent features of bacteria present in the gut.”

The work was done in collaboration with a team at the University of Minnesota, and the results, outlined in a paper titled “Gut Microbiota Diversity across Ethnicities in the United States,” appears today in the journal PLOS Biology.

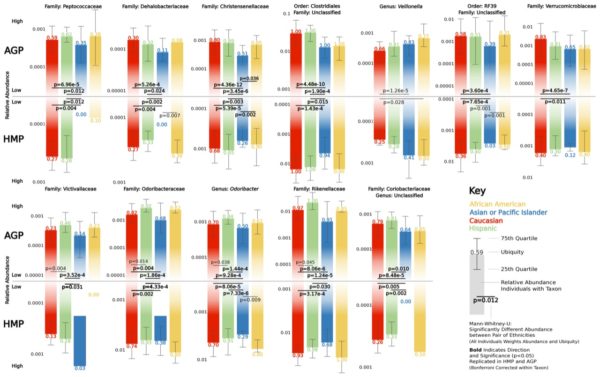

The team discovered 12 particular types of bacteria that regularly vary in abundance by ethnicity. Because ethnicity captures many factors, ranging from diet to genetics, it’s difficult to say why this is, said Andrew Brooks, the Vanderbilt doctoral student in the Vanderbilt Genetics Institute who analyzed data provided by the American Gut Project and Human Microbiome Project. But it’s a baseline for understanding healthy microbiome differences among individuals.

Bordenstein is director of the Vanderbilt Microbiome Initiative, a collaboration among five Vanderbilt schools and colleges to advance microbial discoveries and, ultimately, get them into the hands of doctors for precision and preventative medicine.

“You may buy probiotics over the counter at a drugstore, but those are unlikely to affect your microbiome in a substantial way,” Bordenstein said. “They often are at too low a dose, and they may not even be viable bacteria. Moreover, one size may not fit all. But with more of this kind of research, we can hone in on the relevant differences and doses of bacteria that may reverse illness or prevent it from developing in the first place.”

The work published today was supported by National Institutes of Health training grants 4T32GM08017810, 5T32GM08017809 and 5T32GM0817808; the Vanderbilt Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion; the Vanderbilt Microbiome Initiative, funded by the Trans-Institutional Programs; and an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship.

The 12 bacteria featured in this research are:

- Christensenellaceae

- Clostridiales

- Coriobacteriaceae

- Dehalobacteriaceae

- Odoribacter

- Odoribacteriaceae

- Peptococcaceae

- RF39

- Rikenellaceae

- Veillonella

- Verrucomicrobiaceae

- Victivallaceae