An international team has uncovered the potential to beat obesity at the cellular level, characterizing for the first time a complex, little-understood receptor type that, when activated, shuts off hunger.

Jens Meiler, professor of chemistry and pharmacology at Vanderbilt University, said pharmaceutical companies long have attempted to develop a small-molecule drug that could do just that. But until now, nobody knew exactly what the receptor looked like, making it nearly impossible to design the key to activating it.

Finding the “keyhole”

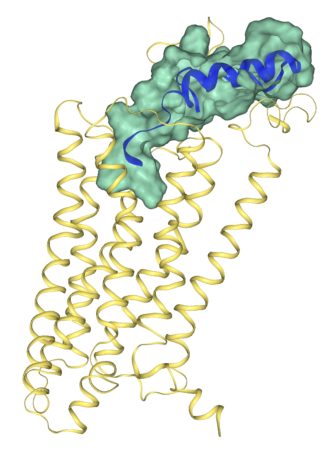

The team determined the first crystal structure for a neuropeptide Y receptor, deciphering the thousands of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and other atoms involved with it and how they bind to one another. Meiler and a Ph.D. student in his laboratory, Brian J. Bender, translated the inherently low-quality data about the atoms’ coordinates to build accurate computer models of both the inactive receptor and what it looks like when activated.

“This is a very important milestone in the drug discovery process,” Meiler said. “The big contribution of this paper is to list the atoms with all the specific coordinates of where they are sitting in space and where they are bound to each other. We’ve actually found where there are little pockets in the structure where we can build a small molecule to bind.

“Before, it was like trying to design a key without knowing the shape of the keyhole.”

Their findings are published today in the journal Nature. Other authors include researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai and Leipzig University in Germany.

Next steps

The next step in this molecular-level research is target validation: proving that the receptor really does control hunger. Past studies revealed that when the receptor is blocked from functioning in mice, they become obese.

“Once you eat, you produce this peptide, it activates the receptor, and then you don’t feel hungry anymore and you stop eating,” Meiler said. “The idea here is that we could upregulate this receptor with a small molecule and create this feeling of not being hungry, so that you eat less.”

Meiler said the Nature paper is part of a much larger, ongoing study that already has produced starting points for the development of potential small-molecule therapeutics.

The breakthrough is possible through a long-standing international collaboration between Vanderbilt and Leipzig Universities with Bender spending months conducting experiments in Leipzig and several scientists from Leipzig traveling to Vanderbilt. The student exchange is supported by the Max Kade Foundation and the National Science Foundation (OISE 1157751). The research at Vanderbilt University is supported by the National Institute of Health (R01 DK097376, R01 GM080403), and the National Science Foundation (CHE 1305874).