The Center for Technology Transfer and Commercialization is taking Vanderbilt researchers’ inventions to new heights

Use the term “inventor,” and what pops to mind?

The wild-haired Dr. Emmett Brown and his time-traveling DeLorean? The unflappable “Q” demonstrating a laser-enabled wristwatch or an exploding attaché case? Perhaps the Absent-Minded Professor and his gooey, green “flubber”?

Hollywood has long portrayed inventors as eccentric, and their inventions as fantastical and futuristic. But at Vanderbilt University, inventing is serious business – and very much rooted in reality. Commercialization of inventions, or “technology transfer,” yields millions of dollars in revenue each year so that the university can continue to support these enterprises. Groundbreaking medical devices, software, educational products and novel drugs created by faculty and staff are shifting paradigms in multiple fields and, more importantly, transforming lives for the better.

Now with a new director, additional staff members and a new name, the Center for Technology Transfer and Commercialization is poised to take Vanderbilt researchers’ inventions to new heights.

At the helm since June 2011 is Assistant Vice Chancellor for Technology Transfer and Intellectual Property Protection Alan Bentley, a Pittsburgh native with a strategic business approach honed during his years heading up the technology transfer office at the prestigious Cleveland Clinic.

“Disclosures and patent applications at Vanderbilt are at an all-time high,” he said. “But it can cost $25,000 for a domestic patent, and thousands more to secure foreign rights. So we are implementing a rigorous process for vetting commercial applications and using a market-driven approach for strategic investments in technologies.”

So what kinds of products fall under CTTC’s purview? No flying cars just yet, but Vanderbilt does boast a list of exciting innovations in various stages of development all over campus, from Peabody College to the Department of Mechanical Engineering. The list includes:

- An exoskeleton that enables a paralyzed person to walk;

- A synthetic scaffold that repairs and heals broken bones;

- Energy-absorbing highway crash cylinders;

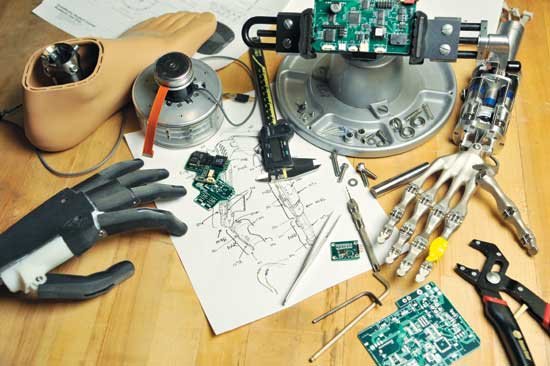

- An anthropomorphic prosthetic arm for amputees;

- New drugs to treat fragile X syndrome, schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease;

- Innovative reading glasses for the visually impaired;

- A super-powerful insect repellent;

- Reading intervention software for middle school students, and more.

Technology transfer at Vanderbilt has come a long way in the past 20 years. Founded in 1990 with just one employee, the then-Office of Technology Transfer was limited in what it could do to protect, promote and commercialize researchers’ intellectual property. Two decades and several name changes later, CTTC is equipped to do more for campus inventors now than in any year since the office opened its doors.

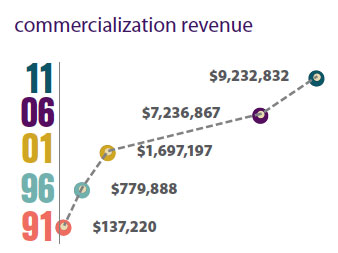

Last year, invention disclosures at Vanderbilt reached an all-time high of 167 compared to 37 in 1991. Thirty-one U.S. patents were issued to Vanderbilt in 2011 compared to seven in 1991. In 2011, Vanderbilt reaped more than $9.2 million in commercialization revenue compared to just $137,220 in 1991. To date, 1,900 disclosures have been made by Vanderbilt faculty and staff.

Last year, invention disclosures at Vanderbilt reached an all-time high of 167 compared to 37 in 1991. Thirty-one U.S. patents were issued to Vanderbilt in 2011 compared to seven in 1991. In 2011, Vanderbilt reaped more than $9.2 million in commercialization revenue compared to just $137,220 in 1991. To date, 1,900 disclosures have been made by Vanderbilt faculty and staff.

One of the biggest improvements for the office is the strategic addition of eight new staff members, six of whom are part of the licensing team. Each licensing staff member is well-versed in a particular field of science and experienced in licensing, intellectual property, marketing, negotiations and other areas that enable them to work seamlessly with researchers, attorneys and the business world.

“We have strategically hired experienced licensing professionals whose skill sets complement the existing expertise of our professional staff,” Bentley said. “We have several attorneys on staff and many Ph.D.s in a variety of disciplines. Our group is very effective at communicating with our faculty members as well as with industry scientists and business people. [rquote]They sit at the boundary between academia and industry and have to understand the unique cultural differences between the two camps.”[/rquote]

Licensing officers first evaluate the commercial viability of each new invention, as well as its market potential and advantages over existing products. They register copyrights, file patents, facilitate additional sponsored research, execute agreements with businesses and track and collect royalties, which are shared between the inventor and Vanderbilt.

“These days, there are more boots on the ground providing more personal service,” said licensing officer Mary Kosinski, who, among other departments, works closely with the Vanderbilt Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery (VCNDD). “That’s a good thing for Vanderbilt.”

It costs a pharmaceutical company up to an estimated $1 billion to bring a new drug to market. In the current weakened U.S. economy, “Big Pharma” is looking more than ever to partner with universities in their drug discovery and development efforts.

“It’s my job to help researchers translate their amazing science into commercial applications that will advance health care as well as fulfill their core academic mission,” Kosinski said. “So in addition to managing patent matters, I interact with companies and connect them to our researchers. It’s important that I understand the rapidly changing field of drug discovery so that I can help the researchers identify and understand the unique and valuable asset they may have created.”

Among the VCNDD researchers’ projects is the development of an exciting new treatment for Parkinson’s disease that alleviates the common side effects of traditional dopamine drug therapy. On the VCNDD’s behalf, CTTC helped negotiate a partnership with the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research in order to bring this potential drug closer to the clinic.

“This partnership is exciting,” Kosinski said. “Vanderbilt is very much on the cutting edge of translating groundbreaking science to the commercial world.”

Jeffrey Conn, director of the VCNDD, believes that having a top-level technology transfer office is critical to advancing such discoveries.“We have that at Vanderbilt,” Conn, the Lee E. Limbird Professor of Pharmacology, said. “What has been so beneficial is having a dedicated tech transfer person in Mary Kosinski.

“Because she can focus primarily on what we are doing, she can really immerse herself in the science and understand the unique issues that are important to the VCNDD in a way we’ve never experienced before. She is exceptionally talented and has incredible instincts for what is important to Vanderbilt and our partners,” he said.

Jeffrey Sonsino, assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute, is anticipating his product – high-powered reading glasses for people with visual impairment – to hit the commercial marketplace this year. His Low Vision Readers combine high intensity LED light with strong powered lenses and prism correction, making it possible for people with macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and inherited retinal diseases to read.

“This will make a big difference in the quality of life for those with vision impairment,” Sonsino said. “Without patent protection, we would not have taken the risk and spent the significant funds to bring this to market.”

This was Sonsino’s first project with CTTC. “It would not have taken off without the support of Peter Rousos (CTTC’s manager of economic new business development),” Sonsino said. “He believed in the project and in my ability to pull it off. That validation was perhaps the most important factor in our success.”

Not yet on the market, but well into development, are the innovative devices of Professor of Mechanical Engineering Michael Goldfarb. He is best known for his group’s “bionic” leg, which features a unique powered knee and ankle that make an amputee’s gait smoother and more natural.

Also in development in Goldfarb’s lab is a dexterous, anthropomorphic prosthetic hand and the Vanderbilt Exoskeleton, a “wearable robot” that allows a paralyzed individual to walk. The ultimate impact of these devices could be life changing for those with amputations and spinal cord damage – and that’s what keeps Goldfarb and his team going.

“I believe strongly that the most direct way to improve the quality of life of persons with disabilities is to make the technology commercially available to them,” Goldfarb said. “The CTTC has been instrumental in protecting and licensing the intellectual property to a commercial partner who we believe can successfully shepherd the technology through the commercialization process. My primary representative at the CTTC, Ashok Choudhury, has invested considerable effort ensuring our technology will be successfully translated through industry partnerships.”

Not all inventions coming out of Vanderbilt are medical devices or drugs. Staff member Mark Dorminy, a programmer/analyst in the Office of Contract and Research Administration, invented ListVUe, a software-based search tool for the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Commerce Control List. Researchers consult the CCL for important information about compliance and federal regulations on export controls. But navigating the list wasn’t always easy. Some of the information could only be found on PDFs, external lists and text files, and at one time, no single search engine was available to sift through them all. Dorminy set out to remedy that.

“I developed the engine that searched all of those files and lists from a single site, and at the time, my supervisor, John Childress, and I were unaware of any commercial products that were similar,” Dorminy said. The initial working system took about three months to develop, but Dorminy has continued to refine and update it over the past seven years.

“CTTC took care of the necessary paperwork to protect the copyright of the invention, and to me, this is of primary importance,” he said. “[lquote]Knowing that my invention has the backing of Vanderbilt University gives me the assurance that it is absolutely safe from infringement.”[/lquote]

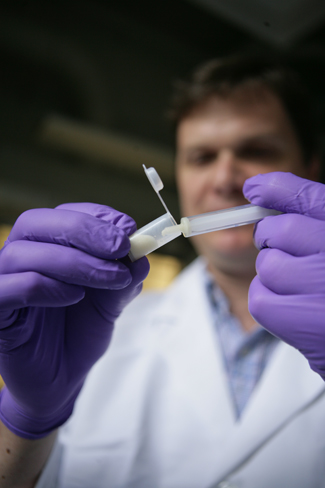

Scott Guelcher, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, has worked closely with CTTC in his development of a novel injectable bone scaffold that stabilizes debilitating fractures. After injected, the viscous liquid fills the fissure and cures, creating a base for the growth of cells and bone regeneration. The result is a weight-bearing repair material that begins to degrade as new bone is formed completely, eliminating painful bone grafting surgeries. CTTC partnered with the Memphis-based spinal therapy company Medtronic to translate the material into a useable therapy, which could significantly alter the current standard of care for many military- and sports-related injuries.

A majority of Vanderbilt’s inventions come out of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, but a number of them are generated by researchers from other parts of campus. For example, Read 180, a reading intervention software program, was developed by Peabody College’s Ted Hasselbring. Licensed and marketed through Scholastic, the computer-guided instruction video and sound teaching methodology has proved successful for middle and high school students across the country. The program is credited with raising grades and lowering truancy and dropout rates.

Besides protecting and marketing individual products, CTTC has facilitated the formation of a number of powerful start-up companies. The formation of Universal Robotics, a multinational company that aims to transform the materials packaging industry, was a result of the work of Vanderbilt researchers who collaborated with NASA to develop a new form of artificial intelligence that enables machines to learn while undertaking difficult and dangerous tasks.

Over time, the researchers and Vanderbilt will likely share in significant royalties as the company grows, Bentley said.

With such a broad range of invention possibilities, the licensing officers never have a dull day.

“Job one is understanding the invention,” Kosinski said. “Is it special? Is it a game-changer?

“There can be a variety of outcomes,” she said. “But in the end, we do what’s best for the faculty member and the university. It’s exciting to be part of the process and an honor to be part of the journey.”