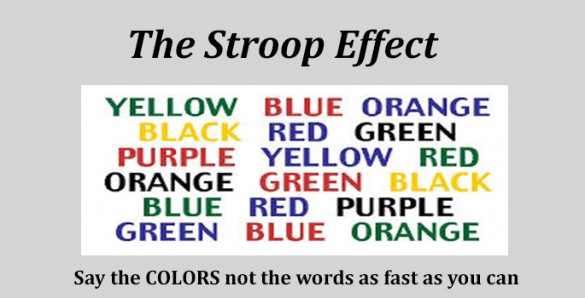

If you look at the word “red” written in green letters, it is significantly easier to say “red” than it is to say “green.”

That is the essence of the Stroop effect, which was discovered in the 1930’s by John Ridley Stroop as part of his doctoral thesis in psychology at George Peabody College for Teachers, which is now Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of education and human development. The discovery, which was published in 1935, has become a classic taught in introductory psychology courses in universities around the world. It is also finding an ever-widening circle of research and clinical applications.

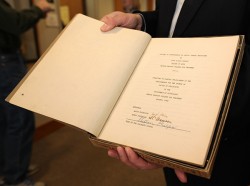

On Friday, February 28, a small group gathered in the lobby of Jessup Hall on the Peabody campus (the first building in the nation built specifically for psychological research) to witness Ridley Stroop’s son, Fred Stroop, and his wife Faye hand over Stroop’s original thesis along with his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees to the university for safe keeping.

“[rquote]This is the most famous task in cognitive psychology,” said Daniel Levin, professor of psychology.[/rquote]

Levin, who is director of graduate studies in Peabody’s psychology and human development department, accepted the historic documents on behalf of the university.

“I use the Stroop effect every year in my introductory class,” Levin said. To do so, he displays a series of non-words in different colored letters and has the students recite the names of the colors aloud. Then he switches to the “conflict condition,” where the non-words are replaced by the names of colors that are different from the colors in which they are displayed: the word red is printed in green letters, the word green is printed in red letters, etc. “It’s amazing how quickly the recitation breaks down,” he said.

“That’s one of the marvelous things about the Stroop effect, everyone can experience it … unlike many of the tasks that we use in cognitive psychology that are subtle and don’t necessarily produce a salient experience,” Levin said.

At the event, Fred Stroop acknowledged that he is one of the few people who can’t experience his father’s famous effect: He has a rare form of color blindness inherited from his mother that interferes with the color-related task.

J. Ridley Stroop was born on a farm 40 miles from Nashville and was the only person in his family to graduate from college. He began preaching the gospel when he was 20 years old and continued to do so throughout his life. He spent nearly 40 years as a teacher and administrator at David Lipscomb College, now Lipscomb University, in Nashville.

Since 1965, Stroop’s thesis has been cited more than 9,900 times in the scientific literature, but it wasn’t until the 1970’s that its importance was generally recognized. In the realm of cognitive psychology, the Stroop effect and the variations that have been developed on the original theme have found increasing importance because they represent a unique window into the interplay between mental processes that are automatic and those that are under conscious control. In a time when new tools like brain mapping and methods like computational modeling have begun spanning the divide between cognitive psychology and neuroscience, the Stroop test is playing an important role in linking mind and brain.

Stroop’s discovery has widespread clinical applications as well. A picture version is being used to diagnose children with learning disabilities. In clinical psychology, it is being used to identify phobias and to diagnose individuals with schizophrenia and attention deficit disorder. It is also being used in drug trials as a general test to determine if the ingredients have any effect on subjects’ cognitive abilities.

According to his son, Stroop was unaware of the growing importance of his discovery when he died in 1973. Toward the end of his life, he had largely abandoned the field of psychology and immersed himself in Biblical studies. “He would say that Christ was the world’s greatest psychologist,” Faye Stroop recalled.

Levin said they hadn’t determined exactly what they will do with the original thesis, but they may add it to the wall display on the Stroop effect in Jessup’s main hallway.

“I teach a small graduate seminar every couple of years and I send the students to the display and ask them to reproduce Stroop’s results,” said Centennial Professor of Psychology Gordon Logan, who attended the ceremony. “They come back with numbers that agree remarkably well with Stroop’s original measurements.”