Julia Velkovska

-

Julia Velkovska: Solving the world’s minuscule mysteries

As Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Physics and chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy, Julia Velkovska studies the tiny particles that form our universe. She focuses on how nuclear matter behaves when confronted with extreme density and temperatures (think trillions of degrees)—similar to the conditions existing microseconds after the big bang, right as the universe was starting to take shape. Just this year, Velkovska and her team of physicists were awarded the 2025 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, along with 13,508 colleagues across four landmark CERN experiments. The prize honors decades of work expanding our understanding of the physical universe. Read MoreApr 7, 2025

-

Boundary-Spanning Genius

For John Jumper, BS’07, the road to winning the Nobel Prize in chemistry began with an interdisciplinary education at Vanderbilt. Read MoreOct 30, 2024

-

36 scholars honored at endowed chair investiture ceremony

Vanderbilt Chancellor Daniel Diermeier and Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs C. Cybele Raver honored 36 scholars from across the university at an endowed chair investiture ceremony on campus March 30. Read MoreMar 31, 2022

-

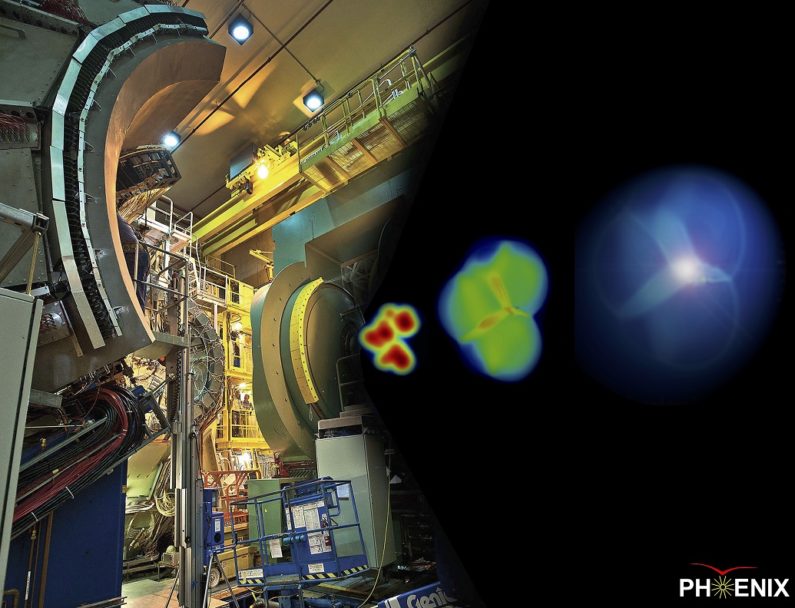

Vanderbilt physicists help find compelling evidence for small drops of perfect fluid

PHENIX publishes new particle-flow measurements to support their case that tiny projectiles create specks of quark-gluon plasma. Read MoreDec 10, 2018

-

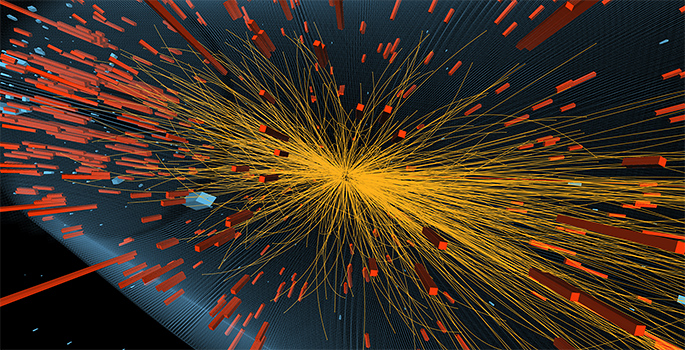

Primordial cosmic soup easier to create than previously thought

In subatomic collisions, physicists have found the signature of primordial cosmic soup, from which all the stuff in the universe formed, at lower energies and in smaller volume than ever before. Read MoreOct 3, 2017

-

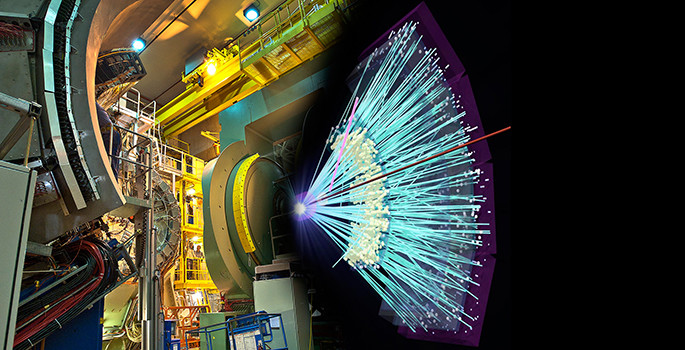

World’s largest atom smashers create world’s smallest droplets

Recent experiments at the world's largest atom smashers are producing liquid drops so small that they raise the question of how small a droplet can be and still remain a liquid. Read MoreOct 2, 2015

-

World’s smallest droplets

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider, the world's most powerful particle accelerator, may have created the smallest drops of liquid made in the lab. Read MoreMay 16, 2013

-

Fermilab Today: The consistency of quark soup

Four Vanderbilt researchers collaborated with scientists from the University of Illinois-Chicago, University of Kansas and MIT to describe the consistency of an unusual fluid produced when atoms of lead are smashed in the Large Hadron Collider. Read MoreMay 16, 2012