Audrey Ellerbee Bowden was born in Queens, New York, to a Christian family for whom serving others was a core part of their faith and purpose.

“Faith without works is dead,” Bowden says, quoting from the Bible.

Bowden grew up in a close-knit family and church community that were always volunteering at food banks, soup kitchens, shelters, schools and anywhere else the church found need.

She brightens as she talks about missions to Ecuador and India with her parents and church, bringing vital materials, rebuilding communities and sharing their faith.

Now she is passing these values to her own children and looks forward to a global mission with their Nashville church as soon as the kids are a bit older.

“I became a biomedical engineer because I want to help people,” Bowden says. Her life in service exposed her to human frailty and demonstrated the importance of good health.

“I have seen firsthand—in low income and high income countries—that ill health can devastate lives and families. My research is dedicated to improving health outcomes in any way that I can, which is also an important way that I can serve.”

During two video interviews from Zurich while on sabbatical with the prestigious ETH Zurich and Collegium Helveticum, Bowden shared her thoughts on science, race, God, failure, invisibility and faith.

This is her story of light.

FINDING LIGHT IN LIFE AND SCIENCE

Bowden is professor of biomedical engineering and leads the Bowden Biomedical Optics Laboratory (biophotonics is the use of optical techniques like imaging to study biological molecules, cells and tissues). She is also an affiliate of the Vanderbilt Institute for Surgery and Engineering and the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health.

After starting her career in electrical engineering, Bowden earned a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering and then did a postdoctoral fellowship in chemistry and chemical biology.

“I was fascinated by so many things that I often found it difficult to choose, but the gravitational pull was optics and then biophotonics,” she says.

It is a logical choice for a woman of science who feels the light of God working in her. So far in her career, Bowden has already found ways to illuminate previously invisible diseases, like bladder cancer, which saves precious time through earlier diagnoses.

Undoubtedly, Bowden’s discoveries will change and save lives, but it is her approach to innovation that will change research and health care.

She describes herself as practical and frugal, and she insists on building solutions that are inclusive—in other words, biophotonic tools and processes that are inexpensive, use readily available materials and are easy to build.

That is an atypical priority for cancer research, but Bowden is not like other researchers.

ENGINEERING PRODIGY

Bowden was only 16 when she started at Princeton University. After graduation (and not yet 21), she was hired as a visiting engineering lecturer for the “Princeton in Asia” program. After exploring Asia for two years, Bowden earned her Ph.D. at Duke, where her education and research were funded by the National Science Foundation and others.

Stanford University offered her a tenure-track position upon graduation, but Bowden deferred for several years to serve first as a legislative aide to Carl Levin, U.S. senator from Michigan.

She was then a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard, where she studied microfluidics and was introduced to its low-cost, point-of-care counterpart, paper-based microfluidics.

It was during this fellowship that Bowden learned how to apply her practical and frugal nature to innovate through scientific research and development. She had the first chance to see her research deployed in a global context during a memorable visit to Haiti.

Bowden joined the faculty of Stanford in 2010, and by the time she left eight years later, she was tenured and had already received a Young Investigator Award from the Air Force and a National Science Foundation CAREER Award for her innovative work on optical coherence tomography.

She was also married to attorney Matthew Bowden and ready to start a family.

RADIANT LIFE UNFOLDS IN NASHVILLE

The Bowdens wanted three children and saw few families of that size in the Bay Area of Northern California; the cost of living was just too high. When her power-commuting husband said he was open to a change, they chose Nashville and Vanderbilt University in 2018.

At Vanderbilt she found another way to serve, becoming a faculty head of house during the 2020–21 academic year—and the COVID-19 pandemic. She and her family moved onto campus and into Zeppos College, one of the university’s residential colleges for upper-division undergraduates.

“I love residential colleges because they are a great place to come home to, especially during a pandemic,” Bowden says. “I feel the same way about Nashville. It is a vibrant and diverse community that offers so many opportunities for our family. We love it here.”

Life in Nashville has also been professionally rewarding for Bowden.

“Vanderbilt is a great fit because of its strength in biophotonics research—the faculty has so many luminaries in the field,” she says. “And the emphasis on cross-disciplinary collaboration has helped us figure out solutions much faster, which is really exciting.”

MOBILIZING LIGHT TO STUDY ADHD

Although Bowden’s work has largely focused on early detection of cancer, she also applies her expertise to studying disorders like ADHD. Bowden and her lab are collaborating with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford to study the disorder in children.

Although neither she nor her team had experience with product development, they designed and built a mobile, light-based alternative to MRI using common materials and existing technologies in partnership with the Wond’ry, Vanderbilt’s Innovation Center.

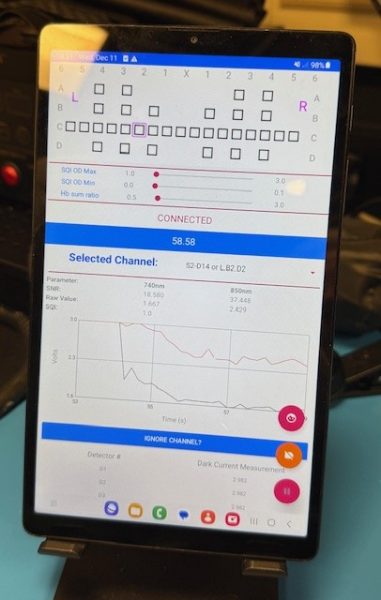

The result is an ingenious, lightweight, adjustable neoprene headband that uses functional near infrared spectroscopy to track blood flow in the prefrontal cortex.

The Stanford team will soon begin clinical studies, using the headband to observe behavioral changes before and after medication doses.

“The impact of ADHD, especially in children, cannot be captured in a traditional MRI machine,” Bowden says. “We needed a mobile, comfortable solution to observe children doing everyday tasks like math problems or memory questions. And of course, it was important to me that we build it as inexpensively as possible so that it can be more widely deployed to low-resource settings.”

Bowden and team even published a paper with DIY instructions for building the headband, and they now assist researchers around the world to build their own.

GUIDING LIGHT

Bowden not only illuminates the body, but she also is a guiding light for other scientists of color. In an interview with the International Society for Optics and Photonics, Bowden described what it is like to be Black in engineering:

“… the notion of standing out when I walk into almost any room in my professional space and being concerned about how I may be perceived is a common experience given my identity as a Black woman. It is like being visible (because I know that I stand out) and invisible (because I may be silenced or ignored) at the same time.”

For Bowden, this challenge is personal and professional. Racial invisibility has plagued biophotonics research and development.

“An ‘inclusive’ solution is not only affordable, but also more accurate for everyone. Unfortunately, there is a long history of flawed biophotonics research when dark-skinned people were not included,” she says.

And it’s not ancient history. As recently as 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, pulse oximeters were delivering inaccurate results for people with darker skin.

Bowden works with BME Unite, a national network of biomedical engineers, and others to expose how racial bias leads to suboptimal outcomes for the scientific community.

LIGHT, SCIENTIFIC AND DIVINE

God’s light inspires Bowden, and she funnels it into biophotonic tools that reveal medical truths and save lives.

“Earlier in life, I connected with this idea that God is a very pure form of light. And from a scientist’s view, this pure light holds unimaginable power, capable of both creating and transforming everything it touches,” she says.

God and science exist in a paramount balance for Bowden.

“My faith has provided support and a rationale for doing more,” she says. “I think that I would have been a lot more easily discouraged without it. Science is full of failure, but my faith helps me remember my purpose.”

- Watch more videos from the Quantum Potential series.

- Listen to the Quantum Potential podcast.

- Follow the latest from the Bowden Biomedical Optics Laboratory.

- Read more research news from Vanderbilt.