By Daniel Diermeier

Photos by Vanderbilt University photographers unless otherwise labeled

America’s institutions of higher learning have always been works in progress, evolving along with their times.

First came the ecclesiastically oriented liberal arts colleges established during colonial times. They were modeled after Oxford and Cambridge and concerned with transmitting classical and theological knowledge. That model eventually gave way to a distinctly American one, which blended liberal arts–based undergraduate education with a commitment to research and graduate education that was characteristic of great German universities of the 1800s.

In the early 20th century, American universities evolved further by expanding their professional education programs to offer degrees in such fields as business and engineering, in addition to traditional disciplines like law and medicine. When the U.S. government became the primary funder of scientific and technical research after World War II, many universities ramped up their research capacities in response. And in the years that followed, universities slowly became more accessible to a wider swath of Americans, thanks to the G.I. Bill, the fight for desegregation, expanded access for women and more.

At any given moment, the definition of what makes a university great has been shaped by its times.

As we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Vanderbilt’s founding, American higher education is at another turning point. Colleges and universities face a barrage of disruptors, including declining enrollment, questions about affordability and equity, and globalization.

Of all the factors in play, none is more prominent than the ascent of digital technology as the dominant force shaping our lives. With science and technology rapidly transforming so many fields and aspects of life, our students need to graduate with a sound understanding of technology and its applications and implications. We can no longer deem as educated a student who knows their history, literature and a second language or two, but who doesn’t know anything about statistics, data analytics or the fundamentals of computing. Subjects that until very recently were considered highly technical are now central to a young person’s ability to understand, contribute to and succeed in the world.

These challenges threaten different institutions in different ways. Movement away from the humanities toward STEM fields, for example, might have greater repercussions at a small liberal arts college than at a big public university. But no matter the institution, this is a moment in which all of higher education must adapt to the ground shifting beneath our feet.

Of all the types of colleges and universities in America, top-tier, private research universities are the best equipped for this time of change. For Vanderbilt in particular, this moment of transition is a moment of enormous opportunity. Stronger than at any other time in our history, we are positioned to do more than just meet the challenges of our times. We have what it takes to thrive and lead—to define and become the great university of this century.

Our Three Advantages

Private research universities like Vanderbilt have three distinct advantages in this changing, technology-driven landscape by virtue of our missions, our capabilities and the work we do every day. These include:

Leading research-active faculty

As the rate of change in many fields accelerates, faculty working at the frontiers of their disciplines are best equipped to provide students with an empowering education that keeps pace with changing knowledge. At Vanderbilt, we’ve made strategic investments in faculty over the years, most recently through Destination Vanderbilt, our $100 million initiative to recruit faculty who are rising stars in their fields.

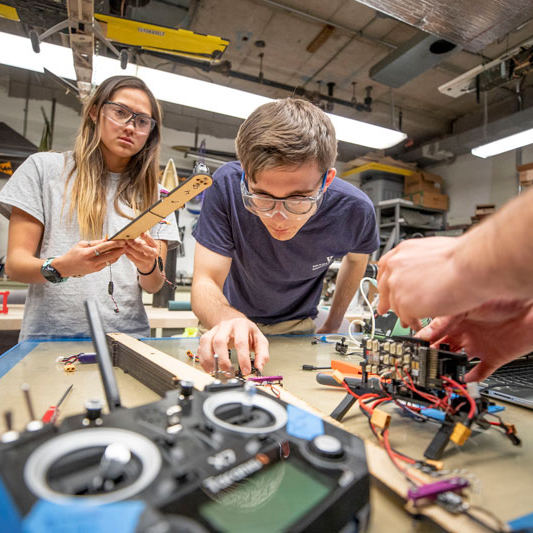

Expansive research infrastructure

Private research universities have long provided leading-edge labs, equipment, libraries and other resources to attract and support the best faculty. In recent years, Vanderbilt has invested millions in facilities, tools and support staff that allow our researchers to explore widely and break new ground. Examples include our Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education, which supports researchers in many fields; updates to the pioneering Warren Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery; and the acquisition of four state-of-the-art mass spectrometers as part of our co-investment in a Mass Spectrometry Center of Excellence at Vanderbilt.

A thriving innovation ecosystem

For the better part of a century, an unmatched stream of breakthroughs from research universities has improved the quality of our lives. Today, with urgent and even existential problems bearing down on humanity, the need for solutions is critical, and research universities like Vanderbilt are uniquely prepared to provide them. Bringing them to scale demands increased collaboration with business, government and nonprofits. At Vanderbilt, we're collaborating more than ever with Middle Tennessee’s community of innovators, entrepreneurs and creators, who operate at a unique nexus of technology, health care, financial services, the arts and more.

What Greatness Means Now

History shows us what happens to universities that don’t rise to the challenges of their times. As Jonathan Cole describes in his 2012 book The Great American University, when the federal research funding system emerged after World War II, some research universities organized themselves to take advantage of it, launching themselves on a course of discovery and relevance. Others didn’t and fell behind.

The universities that seized the moment, as Cole writes in his appraisal of visionary Stanford provost Fred Terman, “embraced a dynamic rather than a static model of the university. This meant not becoming stuck in the historical past, but instead being attentive to what a changing society would require from its great research universities in the future. A university’s leaders … must be open to the dynamics of social and academic change, constantly looking to the future, and not fall prey to looking backward toward the illusions of a disappearing Golden Age.”

At Vanderbilt, looking to the future doesn’t mean abandoning our identity and values. Rather, it means using our momentum and resources to meet the challenges of our time by doing even more of what we do well. But what should that “more” be?

Let’s begin with the non-negotiables. To be truly great in our time, a university must deepen its commitments to its purpose and core values, especially during a time of change. This must include commitments to:

Expanding access

Through leading financial aid programs like Opportunity Vanderbilt, universities like ours have made it possible for more students to enroll, irrespective of their financial resources. But there are still too few lower-income students at the very best universities. We need to expand philanthropic support to eliminate financial barriers to accessing our transformative education. Financial support is needed not only to allow students from all backgrounds to attend Vanderbilt, but also to ensure an environment where they can belong and succeed.

Securing freedom of expression

The last couple of decades have been tough ones for freedom of expression and open inquiry on campuses, with threats coming from politicians and activists across the political spectrum and from internal activism, where often-admirable intentions have at times led to intolerance of opposing views. A research university cannot carry out its mission of transformative education and pathbreaking research without the unfettered flow of ideas, opinions and questions. At Vanderbilt, we’re doubling down on providing open forums for discussion, practicing principled neutrality and teaching students how to respectfully debate across differences.

Increasing research funding

America’s system for funding research and scholarship is the greatest in the world. Its social and economic impact is unmatched. We must work with our elected representatives to sustain and expand it. At the same time, we must step up and invest in our own research capacity, as we’re doing through the Discovery Vanderbilt initiative, led by Provost C. Cybele Raver, which supports faculty and students in the kind of ambitious inquiry and innovation that help change the world.

Providing more support for graduate students

Graduate students and postdoctoral researchers are essential to the model of the research university. Many will become the researchers and teachers of the future. We must provide them with a fair stipend, housing, mentorship and other support to help them realize their full potential.

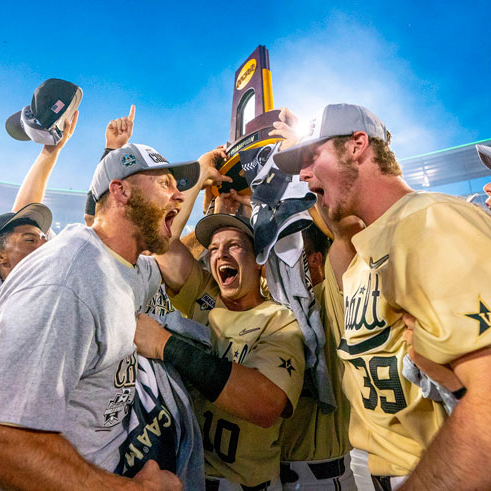

Changing our approach to athletics

College athletics is in a period of dramatic change, raising profound questions about the role of sport in higher education. America’s best universities must lead the way in centering the student-athlete experience on preparation for lifelong growth on and off the field. We must provide an immersive educational experience that supports student-athletes in competing and winning at the highest levels—in athletics and in life. Our Vandy United initiative, which is funding everything from stadium improvements to a center for student-athlete success, is our boldest investment in reimagining what college athletics can be.

Serving the public good above all

Turning our innovations into high-impact solutions requires close partnership with businesses, governments and the broader innovation ecosystem. At the same time, those relationships must not inhibit universities from exercising maximum academic freedom, nor compromise our mission. Our relationships must be transparent and characterized by the greatest integrity and highest ethical behavior.

Reaching Higher, Thinking Bigger

Reflecting on our history and standing among America’s great research universities fills us with pride, but we cannot, and must not, rest on our laurels. We must seize this critical moment for Vanderbilt and higher education. This includes:

Generating more value from scholarship and innovation

By one estimate, every dollar spent on research yields five dollars in social benefit. Yet Vanderbilt, like many research universities, leaves a great deal of social and economic value on the table. How can we turn more of our research into applications—particularly innovations from disciplines other than bench sciences—that help solve urgent problems? Ready pathways exist for fields like pharmacology, biomedicine and engineering. How can we provide them for other fields?

Engaging more deeply with our community

The days of Vanderbilt being an aloof “big gorilla,” as onetime Nashville Mayor Phil Bredesen once put it, are long behind us. Today we readily invest in and partner with organizations that are moving Nashville and Middle Tennessee forward—in urban development, in the arts and in nurturing Tennessee’s innovation ecosystem. As we consider our future, we must ask: How can we leverage even more of what we do to the benefit of our community, our city, our region?

Expanding our presence around the globe

Vanderbilt competes for students and faculty in a global marketplace, and we want the benefits of our discovery and innovation to reach worldwide. How can we increase Vanderbilt’s presence in other countries so that we can engage the most promising students and researchers while more thoroughly integrating the realities of an interconnected world in our teaching, scholarship and research?

Scaling instruction beyond campus

Vanderbilt is highly selective in who we admit, so that we enroll the most capable students and create an environment that fosters an empowering education. But is there a way—through high-quality online learning or some other means—to preserve our on-campus experience while providing education and learning for a broader range of students?

These are just some of the possibilities before us. There surely will be others, and, together, our university community will explore them during our sesquicentennial year and Dare to Grow campaign. But undoubtedly, the great universities of this century will be those who use their resources and capabilities to achieve many of the objectives on this list.

Fully a University

Upon his investiture in 1963, Alexander Heard, Vanderbilt’s fifth chancellor, declared that Vanderbilt’s duty was “to be a university, to be fully a university in the largest modern meaning of that ancient, always changing institution.”

What it means to be “fully a university” has changed since Chancellor Heard’s era, and even more in the 150 years since Cornelius Vanderbilt’s great gift gave Vanderbilt its start. But our duty remains the same: to be a university that unflinchingly engages with the world as it exists in our lives and times.

By virtue of our design, and by virtue of the vision, commitment and generosity of those who have built this university from 1873 until now, we are poised to fulfill that duty. We have what it takes—to dare to grow in bold new ways, to be proud, but not satisfied. Vanderbilt was made for this moment. Let’s not waste any time in doing what this moment asks of us.

Daniel Diermeier is Vanderbilt’s ninth chancellor.