This story will appear in the forthcoming print edition of Vestigo, the School of Medicine Basic Sciences magazine.

Story by Leigh MacMillan

In the early 1960s, young Larry Marnett received his amateur radio license from the Federal Communications Commission. He put up an antenna outside his Kansas City, Kansas, home and began tapping away in Morse code.

“It was just so cool to be ‘talking’ to someone in California or Canada,” Marnett recalled. After a conversation, radio operators often exchanged notes on postcards with their call signs. Marnett had postcards pinned up all over his walls.

“I remember one time I thought I was talking to somebody in Colombia. He was kind of going in and out, and I wasn’t really sure that we had actually talked,” Marnett said. “A week or so later, I got a postcard from him, so I knew that I had talked to somebody in another country that wasn’t even contiguous with the United States.

“It gave me an appreciation that there are people in other places who think the way I do. I would dream about what they were like and what their lives were like.”

Dreaming. Connecting. These themes run through Marnett’s life. They have powered his five-plus decades of research and his progressively complex roles in academic leadership.

Later this year, Marnett will step down as dean of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Basic Sciences, a “school within a school” that he and a dedicated team have built over the past six years. He will return to his research lab full time, knowing that Basic Sciences is thriving as one of the nation’s top biomedical research and doctoral programs.

Becoming a scientist

Marnett didn’t set out to be an academic leader. He didn’t even set out to be a scientist when he started his freshman year at Rockhurst College in Kansas City, Missouri. He had not taken a chemistry course in high school, and he struggled with it in college. By the end of the first semester, though, he managed to score the highest grade on the final, prompting the professor to invite him to try out research.

“I started kind of putzing around in his lab, and then he arranged a summer position for me in an inorganic chemistry lab,” Marnett said. “It was a small school, and it wasn’t much, but I found a home, and it was fun.”

By the time he was a senior, it was clear that he would pursue graduate studies. He chose the chemistry program at Duke University, where he became the first graduate student to work with Ned Porter, a new faculty member in the department, studying free radical chemistry.

Marnett recalls two particular events that occurred during graduate school: a career-changing conversation and a life-shaping connection.

The conversation: Over beers one evening after a seminar, Porter asked Marnett what he was thinking about doing when he completed his Ph.D. Marnett listed some options that did not include academic research.

“What about academia?” Porter asked him. “I’m not good enough to go into academia,” Marnett responded. “Yes, you are,” Porter said.

“At that moment, this switch went off,” Marnett remembered. “I thought, maybe I can do that. It was a really key moment in my career. Ned doesn’t remember saying that,” he said with a laugh.

And the connection: Marnett met and married Nancy Brown. They celebrated their 50th anniversary last year.

“I depend on my wife a lot. She’s got a very good radar—she understands people, and she understands me,” Marnett said of Nancy, whom he described as vivacious, energetic, and focused. “We complement each other well. I’m a dreamer, and she’s a get-it-done kind of person.”

Marnett completed his Ph.D. in 1973, and he and Nancy headed to Stockholm, Sweden, where Marnett worked with Bengt Samuelsson (who won the Nobel Prize in 1982 for his discoveries regarding prostaglandins and related compounds).

“It was a super-exciting time to be there. They had just isolated the prostaglandin endoperoxides that are the key intermediates in prostaglandin biosynthesis,” Marnett said. “I remember the first week I was there, the guy working next to me was dumping platelet extracts on a rabbit aorta strip trying to identify the contractile substance, which turned out to be thromboxane A2.

“I got so turned on by this mix of chemistry and biochemistry and enzymology and pharmacology. I was hooked.”

The experience laid the foundation for his career-long study of the prostaglandin-producing cyclooxygenase enzymes and, like his amateur radio experience, made him aware of the international connectedness of scientific research.

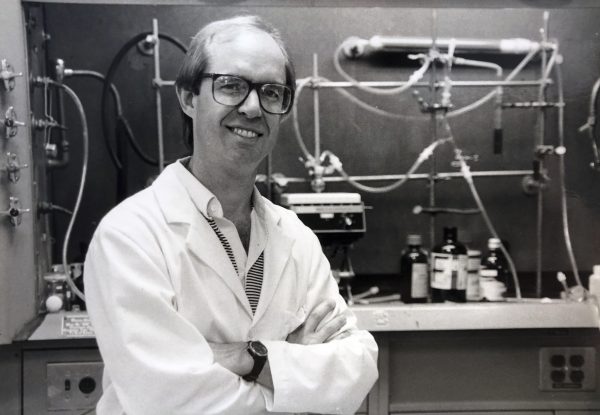

Research legacy

After a year (short postdoctoral fellowships were the norm at the time), Marnett wanted to get back to the U.S. to begin his search for a faculty position. He took a postdoctoral position at Wayne State University, where his intellect and work ethic were noticed, and within a year—despite a near-prohibition on hiring from within—he was appointed to the faculty.

“It was a great place for me to start my independent career because it was a chemistry department with a biochemistry division,” Marnett said. “I didn’t know any biochemistry, but I had to learn it because I was teaching it. I was frequently just 10 minutes ahead of the students and always on the edge of terror that they would ask a question I didn’t know how to answer.”

Marnett advanced to full professor at Wayne State before moving to Vanderbilt in 1989. Multiple members of the Marnett research group moved with him to Vanderbilt, earning his laboratory the nickname “Lemmings.”

“Larry has been a talented, creative, kind and consistent academic mentor to all of his graduate students, postdocs and research staff,” said Brenda Crews, a senior research specialist who worked with Marnett from 1994 until her death in January 2022. Consistent with the lab’s nickname, she added, “I must confess that Larry’s present lab would follow him off a cliff.”

Among his group’s many research discoveries over the years (published in more than 500 research articles), Marnett is most proud of:

- Being one of the first labs to study endogenous sources of DNA damage, and fully characterizing the chemistry and biology of the molecules generated by lipid oxidation and the DNA adducts that they form.

- Completely characterizing the structure and function of the interaction of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (the oldest and most-prescribed drugs) with the cyclooxygenase enzymes COX-1 and COX-2.

- Generating COX-2 specific imaging agents, which could be useful for detecting early cellular changes in cancer, by tethering fluorophores (molecules that fluoresce) and positron emission tomography ligands to modified NSAIDs.

- Discovering that the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol is a selective substrate for COX-2 and that the resulting glyceryl prostaglandins are biologically active.

This last area is where Marnett plans to put his energy going forward. After he steps down as dean, he will spend time on sabbatical recharging and traveling, but then he’ll dive back into his research.

“This connection of COX-2 to endocannabinoids is very exciting, because from the standpoint of inflammation and behavior, those molecules have a biology of their own, and we’ve found novel ways for them to be mobilized. This is what’s next; this is what I want to make sure we get done,” he said.

Academic startups

Marnett credits Fred Guengerich with recruiting him to Vanderbilt. After a symposium where they both spoke, Guengerich approached him, told him about being on a search committee for an endowed chair, and asked if Marnett knew “anybody great” who would be interested. Marnett said he would think about it.

“I called him a few days later and said, ‘Well, Fred, I actually might be interested, but I don’t know if you think I’m great,’” Marnett remembered. “He said, ‘Oh, that’s just what I wanted to hear.’”

The Mary Geddes Stahlman Chair in Cancer Research, which Marnett has held since he joined the faculty, was one of few endowed chairs at the School of Medicine at that time and was independent of a department. “I felt like I’d been recruited by the institution rather than a department; it gave me more of an institutional view from the start,” Marnett said.

Marnett also was appointed director of the A.B. Hancock Jr. Memorial Laboratory for Cancer Research. He used Hancock Lab funds to support institutional recruiting efforts and to provide “seed grants” for projects that moved investigators into new areas or made new connections. He found he had a knack for seeing opportunities for people to team up and do something unique.

“I loved catalyzing people to work together,” Marnett said.

Things were humming along with these efforts, his group’s research, and his editor-in-chief role for the journal he founded, Chemical Research in Toxicology, when Harold “Hal” Moses asked him in 1993 to be the first associate director for research of the newly established Vanderbilt Cancer Center, now the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

“I thought, ‘I don’t know; it sounds fun. It’s probably going to be a lot of work,’” Marnett said. “But here I was in a department with Stanley Cohen and Fred Guengerich and Graham Carpenter, really great scientists, and none of them had endowed chairs. I felt like I could repay this endowed chair that the institution had given me.

“I did not come to Vanderbilt to be a leader, and I quickly figured out what I’d gotten myself into,” Marnett said, laughing.

He valued the opportunity to expand his research-catalyzing activities to a larger scale, invest in core facilities at a time when those resources did not exist, and learn leadership skills by absorbing lessons from Moses, a “fantastic mentor” to Marnett.

“I figured out that I’m an academic startup guy. When you’re starting something, you can’t really plan it out; you just have to do whatever needs to be done. There’s a lot of energy, a lot of elbows in the air. It’s exciting.”

His next “startup” came in 2002, when he worked with Porter (who he had helped recruit to the chemistry department at Vanderbilt) to establish the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology.

“I realized that there was a great opportunity for drug discovery around here, and chemical biology was just taking off as a discipline nationally,” he said. “Ned and I started that, and it went really well. We recruited some real stars to Vanderbilt.”

Building a unicorn

The creation of Basic Sciences presented an unexpected opportunity for Marnett. He had been named associate vice chancellor for research and senior associate dean for biomedical science in 2014, and he learned shortly after that the university and medical center would legally separate in 2016.

It had already been decided that the Basic Sciences departments would remain with the university, but no one knew exactly what that would look like. “Give us your ideas,” Dr. Jeff Balser, dean of the School of Medicine, said to Marnett.

“That year and a half leading up to the split was a very unsettling time as we went back and forth on how Basic Sciences might be structured,” said Marnett, who became dean of the new, undefined entity. “The first eight months after the split were complete chaos. We had no processes in place, and we didn’t even know what the funds flow looked like.”

Marnett assembled a team to help build this ultimate academic startup, including three associate deans: Linda Sealy, for diversity, equity and inclusion; Alyssa Hasty, for faculty; and Chuck Sanders, for research. Roger Chalkley and Kathy Gould in the Office of Biomedical Research Education and Training supported Basic Sciences in areas related to graduate student and postdoctoral fellow training.

“Larry’s passion is research, and he has the gift of being able to take pleasure in the research accomplishments of his colleagues,” Sanders said. “I think this has been a major motivator for him in leading the creation of Basic Sciences and working 24/7 over the past six-plus years to ensure its success.”

Marnett has prioritized programs to give faculty, staff, postdoctoral fellows and students “as many resources as possible to function at their highest level,” Hasty said. “Larry has a vision of what Basic Sciences can be in the future and seeks to establish and fund programs that will last long after he stops being our dean.”

He also focused from the start on making diversity, equity and inclusion an essential part of Basic Sciences, and this commitment “will be one of his lasting legacies,” Sealy said. During Marnett’s tenure, 60 percent of faculty recruits have been women or from underrepresented backgrounds.

“I feel privileged to have had this opportunity to start something really unique,” Marnett said.

“Basic Sciences is a unicorn. We’re sitting between a great university and a great medical center, and we’re doing our own thing with access to all of the resources on both sides. We focus on research, and we train graduate students. It’s almost like a research institute.

“It’s been a lot of fun, and it’s been hard … putting processes into place and then, you know, a pandemic. I believe that the structure we’ve put together is set up for success and should be a model for how basic science is done at universities across the country—a model enabled by the close juxtaposition of the university and its medical school. I can’t wait to see how it goes for the next 10 years.”

Marnett will be watching from his lab, where he’ll no doubt be dreaming and making new connections.