By Michael Blanding

All images courtesy of General Motors

It was a declaration of war unlike any the world had ever seen before.

The comedian Will Ferrell—in an online video that appeared several weeks before it ran as one of this year’s most well-received Super Bowl commercials—indignantly discovers that Norway sells more electric vehicles per capita than the U.S. each year.

“Norway!?” he asks menacingly before punching a hole in a spinning globe. He then sets out to recruit celebrities like Awkwafina and Kenan Thompson to help vanquish this Nordic nemesis, mistakenly stopping in Sweden along the way.

Despite its humorous unveiling, the declaration by legacy vehicle company General Motors that it would phase out combustion engines—the heart of its cars and trucks for more than 100 years—and move to an all-electric fleet by 2035 could have monumental implications for the global auto industry and broad efforts to combat climate change.

The New York Times called the change a “seismic shift by one of the world’s largest automakers,” and environmental groups heaped on praise, with the Environmental Defense Fund trumpeting a “new day in America.”

To institute such a dramatic change in less than 15 years, the company will need to navigate technological challenges and financial pressures while convincing consumers to buy into a future of electric vehicles—which currently account for only an estimated 1 percent to 3 percent of the 250 million vehicles on American roads. Mary Barra, GM’s chairman and CEO, is driving the initiative, but its success also will depend on Vanderbilt alumni who hold key positions in the company.

“We’re doing it because it’s good for the company, good for our customers and good for our planet,” GM President Mark Reuss, BE’86, who began work at the company as a student intern while at Vanderbilt, recently wrote on a company website. In the online post, he went on to declare, “2021 is the tipping point towards EVs. That’s what we believe, and that’s what I believe—and we are committed to making it happen.”

As a sign of that commitment, GM plans to spend $35 billion on electric vehicle production over the next five years. Included in those plans are a factory conversion in Detroit—called “Factory ZERO” in a nod to the goal of zero tailpipe emissions—and four new battery cell manufacturing plants, including two already under construction in Lordstown, Ohio, and Spring Hill, Tennessee.

Overseeing those investments will fall to Paul Jacobson, MBA’97, who became the company’s chief financial officer in December, fresh from a successful turnaround at Delta Air Lines. “The opportunity to join an iconic company at a once-in-a-lifetime point of transformation is really exciting,” he says. “It’s the transformation of a company within an industry that is also transforming.”

Jacobson remembers learning as a student at Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management about GM’s innovative management practices during a visit to its Saturn plant in Spring Hill. While he focused on corporate finance in earning his MBA, he now finds himself drawing on lessons in manufacturing from his time at Owen.

“The size and scale of General Motors is astounding, and it’s brought back a lot of memories of those operations classes,” he says.

The key to succeeding in EVs will be taking advantage of that scale, Jacobson continues. GM has set an ambitious goal of launching 30 new electric vehicle models globally by 2025, at which point the company plans to sell a million EVs annually.

“The business is all about driving down manufacturing costs and being able to pass those savings along to the consumer,” he says. As well as providing options at various price points, he adds, the range of models will signal to investors that the company is serious. “We need to be able to articulate a roadmap for investors so they can understand why they should be confident we can execute on this.”

DESIGN GOES ELECTRIC

While it may seem to some observers that GM’s announcement came out of nowhere in January, the company has a long history of developing EVs, starting with its attempts at building a car called the EV1 in the 1990s. When that car proved unprofitable, the company tried again two decades later with the Chevrolet Volt, a hybrid vehicle that could run on battery power for 50 miles or so before its combustion engine would kick in.

Overseeing the design of that car was Bob Boniface, BA’87, who now is director of global design for GM’s Buick brand. “I started working on the Volt concept in 2006, so I’ve had a ringside seat going on 15 years,” says Boniface, whose father was a car collector and who spent hours when he was young drawing pictures of cars.

"Part of our role is never to accept the status quo"

After graduating from the College of Arts and Science with a bachelor’s in psychology and business administration, Boniface took a job at a mutual fund company in Boston. He never lost his passion for car design, however, and often found himself hunched over his drafting table at home during his spare time. Eventually he decided to make a clean break from his finance career and enrolled in the transportation design program at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

“I dropped everything and moved to Detroit,” Boniface says. “The rest was history.”

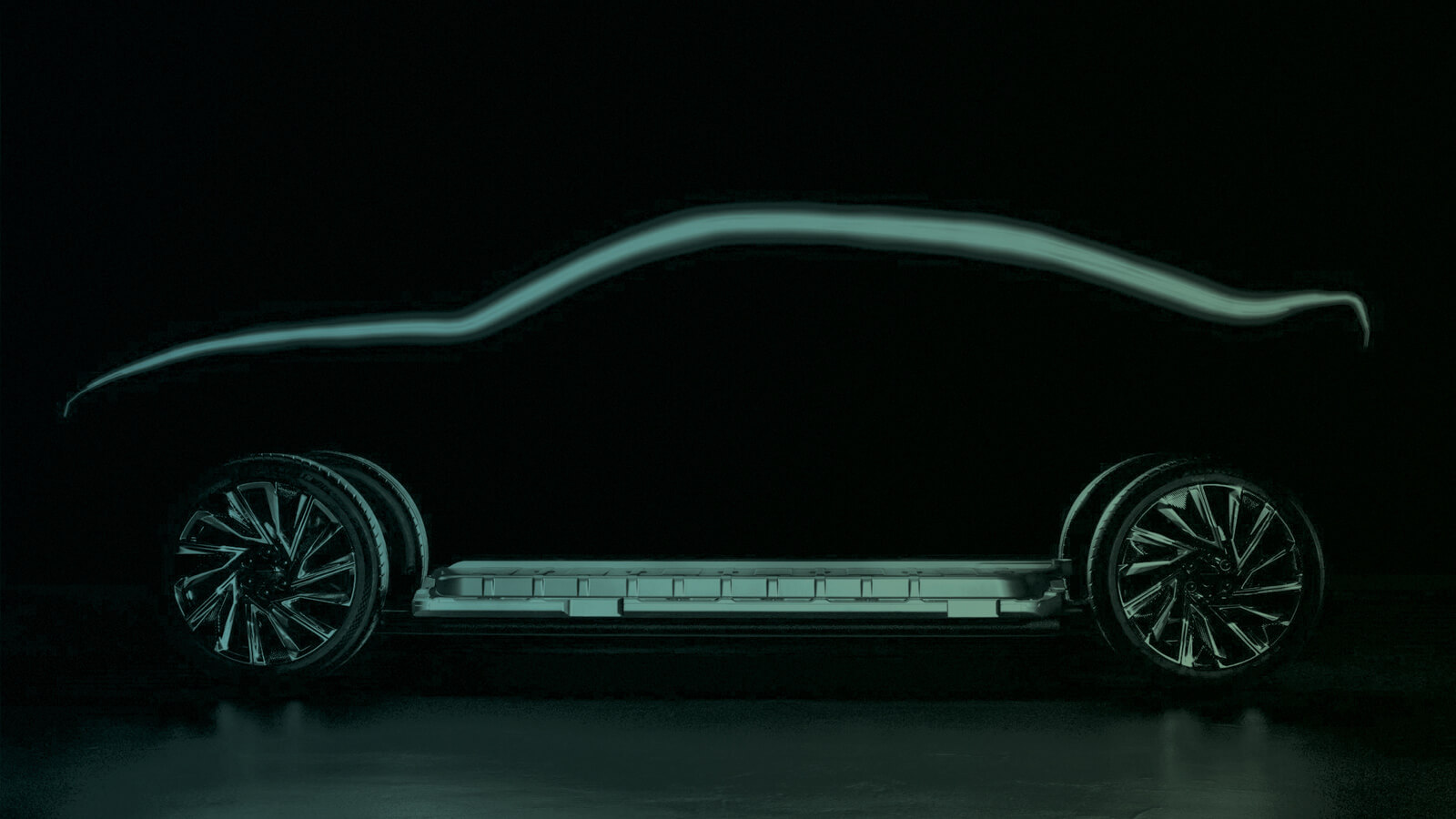

The biggest difficulty in designing an EV, he says, is finding the right balance between performance and style. “You have to put the battery someplace, and they are pretty big and generally rectilinear in shape,” he says. “The aerodynamic concerns are different and present their own challenges.”

At the same time, he says, designers feel an aesthetic imperative to create a stylish car with a futuristic look. For example on the Volt, in solving for aerodynamic and aesthetic issues during wind tunnel testing, the team worked to fine-tune the exterior body. At one point they made a 10-millimeter adjustment to the spoiler, which resulted in an additional one-half mile of driving range.

“You have to be open to happy accidents,” he says. “Part of our role as designers is never to accept the status quo.”

Unveiled as a concept car in 2007, the Volt fell victim to bad timing, just as the economy collapsed and auto companies fell into near-

bankruptcy. But GM began trying again to develop electric vehicles after Barra became CEO in 2014.

The biggest challenge, says Jacobson, is the perception by consumers that the range of EVs are limited by their batteries. “While your primary charging location will be your home, we know the value of road trips, so we want people to know they have the charging capacity when they want to go on a long drive,” Jacobson says.

While bigger batteries cost more, smaller batteries hold less power. “It’s a tradeoff between cost and range, and we don’t want to sacrifice range,” he says. That means finding a way to reduce costs. “So we’re really focused on battery chemistry.”

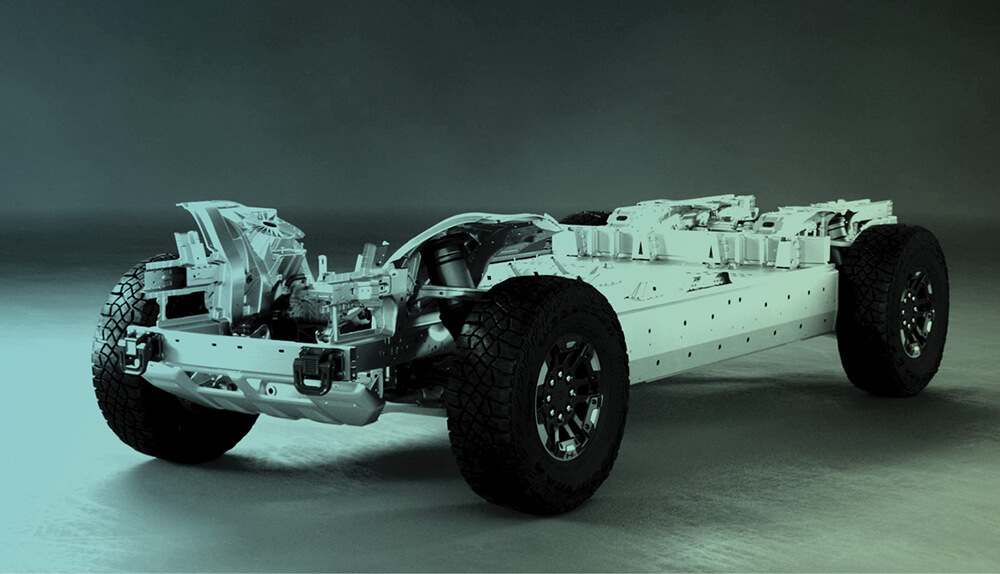

Last year, GM revealed a battery platform the company calls Ultium, which uses a special battery cell design that can be stacked vertically or horizontally to allow for more flexible configuration in the design. In addition, the chemistry replaces much of the expensive cobalt with cheaper aluminum, to achieve higher power at lower cost.

“It’s more flexible as a platform than older batteries and also represents substantial performance improvement in charge capability, capacity and other factors,” says Gabrielle Tate, BE’16, a design release engineer who works on battery design for the GMC Hummer EV.

As a student in the School of Engineering, Tate joined the Vanderbilt Motorsports team, working under mentor Phil Davis to design and build a car to compete at the annual Formula Society of Automotive Engineers competition.

“All of my professors at Vanderbilt were unfailingly supportive of my decision to work in automotive,” she says. “Nobody ever told me what I could not do—on the contrary, frequently they told me I could do things I thought I could not.”

Now she is helping GM engineers achieve once-unheard-of ranges of 400 miles or more on a single battery charge, comparable with industry leader Tesla. (Currently, GM is working with lithium-metal battery company SolidEnergy Systems on a next-generation battery it hopes will reduce costs and increase range further.) The batteries, say Tate, are also easier to service, so they can be quickly switched out or repaired locally. “I think that will be critical for widespread adoption of EVs,” she says.

SELLING THE FUTURE

While GM may be the first major car manufacturer to take the plunge into an electric future, the conditions that led to the company’s announcement have been in the works for a while, says Zdravka “Zee” Tzankova, an associate professor of sociology at Vanderbilt who studies environmental and energy governance. She cites pressure for more sustainability in the automotive industry from environmental groups and, more importantly, from investors who have been increasingly concerned about companies’ exposure to climate risk.

“Stakeholder pressures do not always work, but this has been a momentous set of pressures,” she says. And while the federal government has been slow to act on climate change, states have led the way in increasing regulations. Most notably, California has set stringent fuel-efficiency standards and issued a recent executive order mandating that all new vehicles sold after 2035 be zero-emission.

“There is starting to be some regulatory writing on the wall signaling the expectation for an all-EV fleet in the U.S. in the future,” says Tzankova, who expects that GM’s announcement will touch off a scramble by Ford, Chrysler and other car manufacturers to accelerate their production of EVs.

I have no doubt that when more people have a chance to drive an ev they won't want to go back

The fact that GM has set a time-bound goal for its transformation by 2035 is a hopeful sign, Tzankova says, as is the fact that the company has set an initial goal for 30 models by 2025. “Clear interim targets make the larger all-electric commitment more credible and more likely to be met,” she says.

External environmental pressures are not the only element in play, however. “Another factor to look at is to what extent meeting a particular sustainability or climate commitment is under direct control of the company itself,” Tzankova says. When retailers like Walmart set ambitious goals to reduce their carbon footprint, their ability to meet such goals is almost entirely dependent on partners in their supply chain, such as food suppliers.

On the one hand, GM has an advantage in the fact that it is designing and selling the cars, but it also relies to some extent on a public infrastructure of charging stations to enable the technology—a fact Reuss points out in his online post.

“We have a long way to go before cities have charging infrastructure so all EV owners can charge fast and easy at home, at work and on-the-go,” he wrote. The company has committed initially to installing home chargers for customers with every EV purchase and is partnering with company EVgo to add 2,700 fast-charging stations nationwide.

Another factor Tzankova looks for in corporate sustainability efforts is how willing firms are to use their clout on the public stage. “How are these companies working with stakeholders and flexing their political power to lobby for the kind of policy and regulatory changes that would help them meet their commitments?” she asks.

On that front, at least, GM has been aggressively pushing for changes—urging Congress and the Biden administration to invest in EV charging infrastructure, especially along highways and in urban areas. The company also has advocated for tax credits that would not only incentivize consumers to buy EVs but also encourage supply-chain companies to establish manufacturing capacity for the vehicle components.

None of these factors will matter, though, if consumers don’t embrace an electric future. One way to sell drivers on EVs is to highlight the instant torque that an electric motor provides, compared to the prolonged revving required by a combustion engine. GM executives stress how much fun the cars are to drive, with an acceleration that puts gas cars to shame. “EVs are a blast to drive,” Reuss enthused in his online post. “I have no doubt that when more people have a chance to drive an EV, they won’t want to go back.”

Driving pleasure, however, is only one component that goes into the mind of a consumer when they open up their wallet for a new car. “Notwo customers are equal,” Jacobson says. “Some are attracted by price, some by environmental stewardship, some by style.”

Vanderbilt Professor of Marketing Steve Hoeffler anticipates that price will become less of an issue as car companies start manufacturing at scale and developing more efficient battery technology. “At some point it crosses over, and buying gas gets more expensive,” says Hoeffler, who focuses on consumer adoption of innovative technologies.

Bigger factors in his mind are the uncertainty that comes with the decreased range of the vehicles and the worry about finding a charger when you need one. “Consumers may understand the benefits associated with a new product but still be uncertain about their ability to actually acquire those benefits,” he says. “One of the big uncertainties about electric is ‘What happens if I need to drive 500 miles?’”

To overcome those worries, he recommends GM and other companies employ a marketing concept known as “narrative transportation,” in which customers are immersed in a story that allays their fears.

“Let’s pretend I have a kid in college in Chicago, and I routinely go up and visit him every couple of months,” Hoeffler offers as an example. A narrative could show that fictitious consumer stopping at a favorite fast-charging station for 90 minutes halfway along the 500-mile trip. “I sit in a Cracker Barrel and have lunch and then make my way, so it becomes part of the experience,” he says. “You could even have fun stuff—like I no longer stop at a gas station, so I have to bring Windex with me to clean my windshield.”

Creating such stories for a range of consumers and circumstances could help people overcome their trepidation over electric vehicles and focus on other elements—such as a desire to help the environment or to buy an EV as a stylish status symbol—that might speed their decision to purchase.

“To some degree it all has to fit together, and the whole package has to be something that appeals to the consumer,” Hoeffler says. Either way, he adds, “With the electric vehicle market set to explode, it’s going to make for a pretty lively fight between GM and its competitors, and it’s going to be fun to watch it evolve.”

However that evolution takes place over the next decade and beyond, Vanderbilt’s legacy will play a role in what is sure to be a greater acceptance of electric vehicles. “It’s incredibly humbling to be here and rewarding to know that the Vanderbilt journey was part of that,” Jacobson says. “I wouldn’t be here without my time at Owen—and I’m excited for what the future holds.”