By Jennifer P. Johnston

Illustration by Carlo Giambarresi

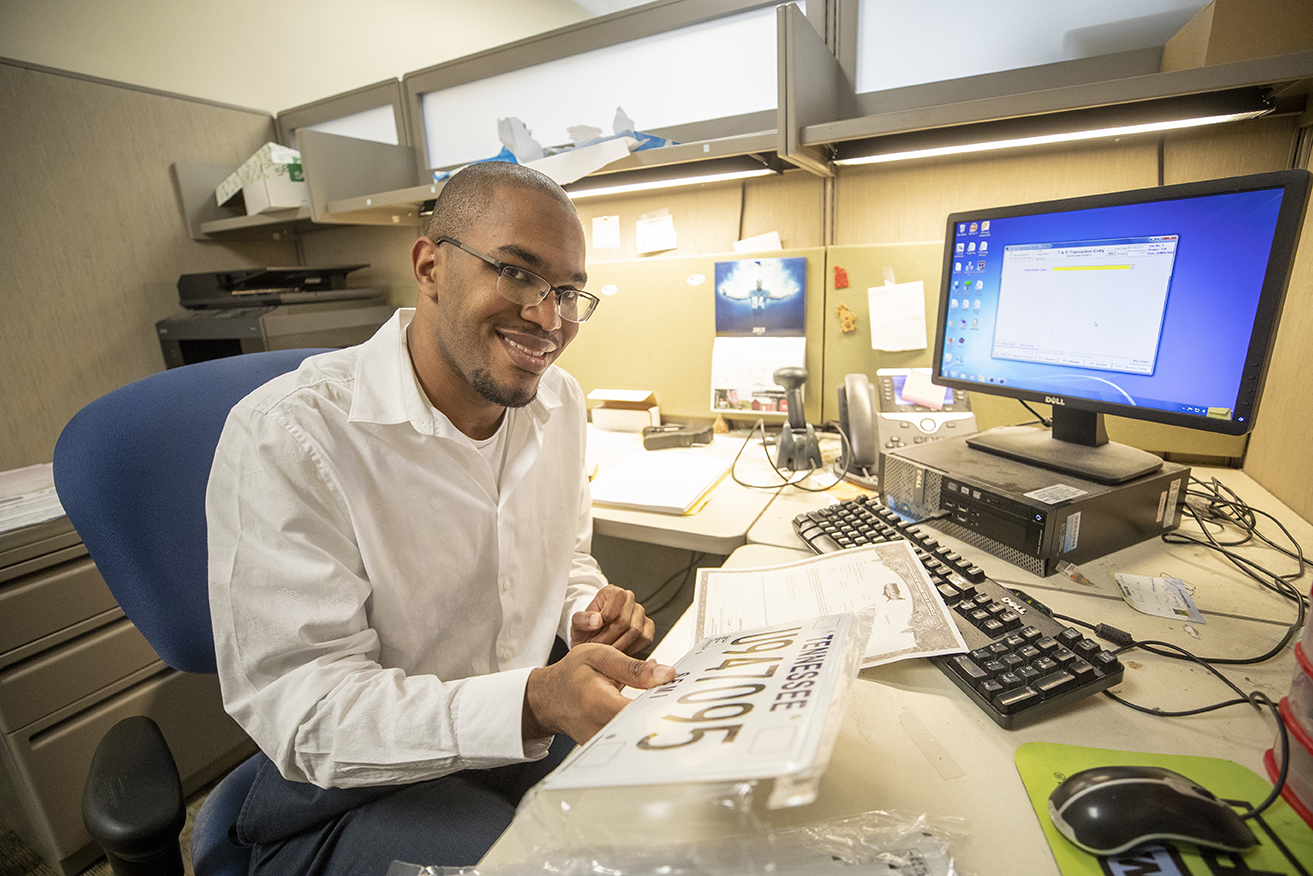

Jamal Underwood begins every workday with a humble greeting for his co-workers in the Davidson County Clerk’s Office in downtown Nashville.

“I say good morning to everybody, I shake hands, I pat them on the back, and I tell them to have a blessed day, that I love them and I’m there for them,” says Underwood, 21, a 2017 graduate of Next Steps at Vanderbilt.

A whiz at data entry, typing with accuracy at 90 words a minute, he has turned his learning differences into strengths. After a year on the job, he received a promotion from part-time to full-time employment.

“He has earned his way and proven himself,” says his boss, Davidson County Clerk Brenda Wynn. “Jamal is hardworking, dedicated and has a great attitude. He is an ideal employee.”

For Underwood, who is on the autism spectrum, full-time employment is about more than just earning an income. This opportunity represents a path to leading a productive, fulfilling and independent life.

“People like Jamal have something to offer,” says his mother, Geri Towles. “They just need a chance.”

Helping young people pursue their best lives

The drive to create communities of belonging for people with disabilities is rooted in Peabody’s history, beginning with the vision of early pioneers such as the late Susan Gray, a faculty member and national authority on early education of children marginalized because of race, socio-economics or ability.

The scholarship of Erik W. Carter, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Special Education, builds on that tradition of inclusion.

“A central focus of my work now is supporting young people with significant disabilities to have a flourishing life, an enviable life, a life that anyone else might want to have for themselves,” says Carter, who oversees many programs and partnerships that further this goal.

One of those programs is Next Steps, the first of its kind in the state of Tennessee. It is a four-year inclusive post-secondary education program in which students take part in Vanderbilt classes, receive job and life-skills training and participate in internships. Along the way they go to athletics events, eat in the dining halls and make new friends on Vanderbilt’s 333-acre campus.

Underwood was the keynote speaker at his Next Steps graduation in 2017, addressing friends, family, students and local reporters with humor, warmth and enthusiasm. A beaming Underwood recounted being diagnosed with autism in 1999 at Vanderbilt as a child, and entering the Next Steps program years later as a shy and withdrawn young man.

“… Fast-forward 18 years, God opened the door for me to come to Next Steps and to be on this very same campus where I was diagnosed,” he said to the teary-eyed gathering. “This innovative program has opened so many doors for me. Next Steps has allowed me to meet so many new friends and colleagues … They will have a special place in my heart and life forever.”

Underwood credits the nationally recognized program with helping him develop a greater sense of confidence and independence. “I’ve learned how to use my abilities and go outside my boundaries, like learning how to use the bus system, learning how to cook, and taking classes with typical Vanderbilt students,” he says. His internship at the county clerk’s office led to his current employment.

Putting faith to work

Peabody’s close collaborations with the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center and Vanderbilt University Medical Center have been an asset to Carter in his work.

“There is no better place to do this,” Carter says. “Our entire community is investing in supporting the whole person across their life span. And we share a commitment to carrying out the rigorous, relevant scholarship it takes to bring the right combination of services, supports and relationships that lead to the flourishing of people with disabilities.”

Helping young people with learning differences contribute fully and meaningfully in the workforce isn’t easy. It requires a “constellation” of partners and allies, from families to educators to local organizations, Carter says.

“The things that young people with disabilities want for themselves are the things that every young person hopes for—a good job, close friends, involvement in the community, a college degree and a great place to live. Even more, it’s a place to belong, and the chance to contribute to their community,” he says. “The challenge is that these outcomes tend not to materialize for young people with disabilities unless we do things differently than we have in the past.”

That’s why Carter has taken a unique approach to his work. He has focused his efforts on engaging partners throughout the community, including faith groups.

“We are all working hard to improve our service systems. But we have to think beyond these boundaries. Services can be good for lots of things, but they will always be insufficient to meet people’s deepest needs of belonging and meaningful contributions,” Carter says.

Among other collaborations, Carter’s Putting Faith to Work initiative partners with local congregations like Christ Presbyterian Church in Nashville, where committed church members and staff help young people with disabilities prepare for life in the larger community, including finding employment opportunities.

Cheryl Roach has watched her son, Nathan, 24, experience tremendous growth as part of this collaborative. Their church gave Nathan an opportunity to volunteer once a week and learn tasks and job skills so that he could begin to prepare for employment. The first task he took on was lining up the water bottles that the church sets out for members on Sunday mornings. He has progressed to the more detailed work of preparing communion trays.

Cheryl believes that Nathan “is still growing and there’s potential, but it definitely takes people around him to change and to invest and it’s not easy.”

For Nathan to stay focused, Cheryl says he needs purpose. “Having this on his calendar has helped him understand the concept of ‘job,’ and every Friday he knows there’s something to look forward to.”

Nathan, who has autism and an intellectual disability, is always accompanied by an assistant, who provides transportation, keeps him on task and provides support if needed. Cheryl has observed change both in Nathan and his workplace. Where once he might have knocked over the water bottles in frustration, he now takes pride in lining them up neatly. But she has also seen how Nathan’s presence has inspired positive change in others. Those who may have been hesitant or even skeptical about Nathan helping out have become encouraging allies, she says.

Inclusion is good for everybody

Carter emphasizes how important it is to show communities that they are better off because they are inclusive of people with disabilities.

“For a long time in our field, research focused on showing how inclusion in schools and community programs is good for people with disabilities. And it definitely is. But that narrow storyline has not yet changed the landscape substantially,” he says. “Our focus has now shifted to emphasizing how the whole community itself is better and richer because it is inclusive. Diversifying your workforce is better for the place of business, there’s no higher risk to safety, there’s better employee retention, and it changes the workplace culture in many ways.”

Carter has found an ally in Vanderbilt astrophysicist Keivan Stassun, who actively recruits underrepresented groups into his lab, including those whose brains process information differently. Those efforts recently were featured in Nature, a high-impact academic journal.

Postdoctoral researcher Dave Caudel, PhD’17, brings to Stassun’s lab his unique way of processing the world as a person on the autism spectrum. His point of entry was the Fisk–Vanderbilt Master’s-to-Ph.D. Bridge Program, an initiative to help underrepresented groups succeed in science.

Caudel is now executive director of Stassun’s newly launched Vanderbilt Initiative for Autism, Innovation and the Workforce, devoted to developing a strength-based understanding of neuro-diverse capabilities.

Encouraging neuro-diversity brings fresh perspective and forces more precise communication in the workplace, with the pay-off a dissolving of cultural biases and misunderstandings, says Stassun, Stevenson Professor of Physics and Astronomy.

“I’m intentionally bringing in people from diverse backgrounds and with diverse ways of thinking because it forces us all out of easy assumptions,” he says.

Vanderbilt increasingly is being recognized for inclusion and diversity, and now, “inclusion of the neuro-diverse is a natural next step for Vanderbilt,” he says.

This was articulated powerfully in a recent opinion piece in the Vanderbilt Hustler student newspaper by Claire Barnett, a Vanderbilt undergraduate who works with Stassun.

“It’s time for us to start thinking about autism differently,” Barnett wrote. “Rather than defaulting to classification as a disability, we should recognize autism and other neurological differences as a part of human diversity.”

Carter agrees Vanderbilt is making significant steps toward inclusion and diversity, but that the university shouldn’t get comfortable just yet.

“When our entire Vanderbilt community is convinced that we are better because people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are learning, working and contributing here—that they are indispensable members of this community—then we will know we have arrived,” Carter says. “But we have to be far more intentional and intensive and individualized about how we support their presence and participation.”

Training, development and support

In the current academic achievement-oriented environment, the importance of providing training for the development of appropriate workplace skills sometimes is overlooked, says Peabody alumna Linda Bambara, EdD’85. Bambara’s research into effective peer-mediated interventions for high school students with autism began with a small grant she received from Autism Speaks with Carolyn Hughes, professor of special education, emerita.

“Individuals with disabilities have much to contribute to our society, just like anyone else,” says Bambara, who now serves as professor and program director of special education at Lehigh University. “This means that we not only prepare individuals with disabilities to do the job, but we also support them in developing critical social-communication skills needed for forming positive relationships with others.”

One avenue for developing those important social skills for students enrolled in Next Steps, for example, is through the Vanderbilt AmbassaDores, a student organization that provides peer mentorship. Each student in the Next Steps program has a circle of support composed of six to eight AmbassaDores who help them find their way around campus, navigate social settings and commiserate about their joys and fears.

“Every parent of a student in the Next Steps program would be in 100 percent agreement that the AmbassaDores help them grow, move outside their comfort zone and expand their horizons,” says Monique Bernstein. Her daughter Caitlin “Cat” Bernstein, who graduated from Next Steps in 2015, continues to nurture and enjoy the deep friendships she formed with AmbassaDores during her time at Vanderbilt.

Cat originally considered becoming a teacher but through a Next Steps internship learned she’s better suited to data sets than squirming preschoolers. Now, she assists with evaluation forms and databases for Carter’s multiple projects. She lends her perspective to weekly meetings on topics such as how to simplify evaluation forms used in the research projects.

“Working has made my life better because I’m more sociable and independent and talkative,” says Cat, who has learning differences associated with Joubert Syndrome. “I’m more productive and I get stuff done.”

Cat says that through work she has learned to express her abilities. “Don’t hide what you can’t do,” she tells others with similar challenges. “Show what you can do.”

Monique admits she had concerns about Cat taking on a job. “I was very nervous about her personal safety in the workplace, being out in the ‘big, cold world,’ ” she says. “But once she started working and she was successful, we could see how proud of herself she was and how she really loved contributing to the workforce and interacting with adults.”

With the job came consumer skills and a desire to take greater care of her appearance, including healthy lifestyle choices such as trying new exercise classes or joining friends after work for book signings or lecture series.

Now the family is talking about independent living for Cat. “I feel like that is feasible and it’s something—at some point, with support—she’s looking forward to,” says Monique. “It’s all tied together—education, employment, living. We’re moving in the right direction.”

Geri, Jamal’s mother, has worked through similar doubts and concerns, but now she sees how much he enjoys being a part of the workforce and having a greater measure of independence. Knowing that her son is surrounded by a supportive community, Geri says she can now focus on her No. 1 task: “To be his mother and love him unconditionally.”