A damaging bacteria with an uncanny ability to pass itself from insect mothers to eggs meets its genomic match in a tiny variety of parasitic wasp, a recent discovery by Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Seth Bordenstein and his team has shown.

Offspring of insects infected with the bacteria Wolbachia often die or are converted from male to female. Bordenstein’s team studied Nasonia parasitic wasps that are only about the size of a sesame seed, and they serve as one of the best models to dissect and characterize the evolution of insect genomes.

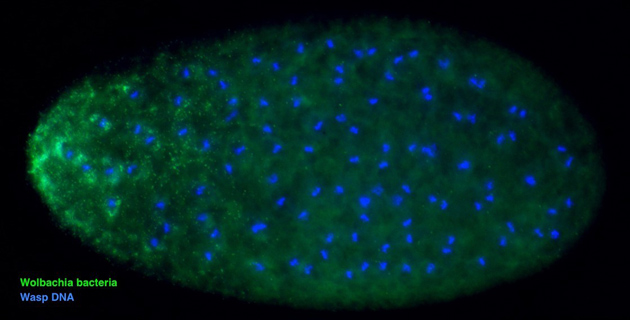

Inside the wasp’s reproductive organs, Wolbachia hide out and pass from the mother’s ovaries to developing eggs to ensure the bacteria’s hidden survival to the next generation.

While high levels of Wolbachia in the ovaries are key for the bacteria’s transmission to insect offspring, too much Wolbachia comes at a heavy cost. The host suffers from reduced lifespan in some insects and fewer eggs in others, specifically in the Nasonia wasps. To balance the opposing evolutionary interests of the wasp and bacteria, an ongoing arms race can occur between the Nasonia wasp genome and that of the Wolbachia infection.

The wasp’s defense system to combat unchecked Wolbachia remained unknown until Ph.D. student Edward van Opstal in the Bordenstein Lab helped detect it. Through the use of several different genetic and fluorescent microscopy tools, one gene from among the many thousands was found to suppress Wolbachia and its transfer to the developing egg.

The genetic signatures in this gene can be used to infer evolution that happened in the past. They indicate that the wasp’s countermeasure to suppress Wolbachia gave it an evolutionary benefit over wasps that lacked this same genetic signature.

The team also found that, in distant relatives of the wasp, the genetic signatures in this gene are different, and it becomes difficult to detect the presence of this gene in their genomes. Thus, it appears that the genetic toolkit used by this wasp species could be highly specific to its own arms race with Wolbachia.

“The broad lesson is that across the kingdom, animals may evolve to control their transmitted bacteria by independent and different means. Mom knows best, but moms in each animal species likely control proliferation of infections in their offspring in unique ways,” Bordenstein states.

The discovery is described in the Current Biology paper, “The maternal effect gene Wds controls Wolbachia titer in Nasonia.” Co-authors of the paper include Vanderbilt graduate alumnus Lisa Funkhouser-Jones and Vanderbilt undergraduate Ananya Sharma.

The Bordenstein Lab’s research also includes using Wolbachia as a defense against mosquito-borne diseases such as Zika and dengue.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation award IOS 1456778, the Vanderbilt Microbiome Initiative, and Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Shared Resources (supported by NIH grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, DK59637 and EY08126).