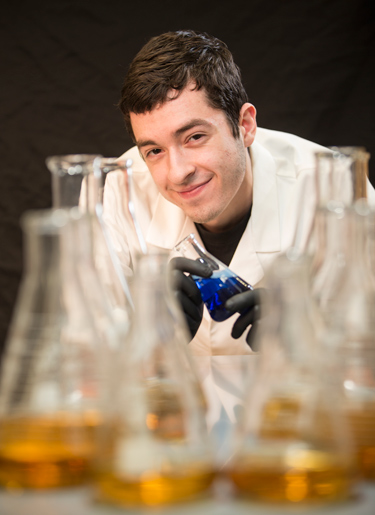

When Boston native Jarrod Shilts arrived at Vanderbilt, he brought with him a strong interest in synthetic biology—a discipline devoted to designing and creating biological molecules that don’t exist in the natural world and using them to redesign existing biological systems.

“This is a very new field. The foundational studies have all been published since 2000,” Shilts explained. “As a result, most universities, including Vanderbilt, don’t have programs or courses on synthetic biology.”

While a first-year student, Shilts saw a way to help plug this gap by setting up an undergraduate synthetic biology lab. He got the idea from student projects conducted at MIT in 2003 and 2004 that led to an annual competition called the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition.

“When we proposed this idea to several deans and department chairs at Vanderbilt, they were very supportive,” Shilts said. As a result, he became the co-founder and director of Vanderbilt’s iGEM Lab. Under his leadership, the lab has successfully completed a number of research projects and entered them in the annual competition.

“We have a core group ranging from six to eight students from a number of different disciplines, including mathematics, biology, computer science, chemistry and chemical engineering,” Shilts said. “We get together and brainstorm. [rquote]So, if I get an idea but don’t know how to do the math or the programming that is required, there is someone in the group who can help.”[/rquote]

When Shilts got interested in the subject of mutation hot spots—certain areas in the genome that have higher-than-average mutation rates—he was able to enlist the expertise of other lab members. The result was an innovative software program that can estimate the likely mutation rate of any gene sequence—a tool that can help synthetic biologists design systems that are resistant to mutations. The project received a silver medal at last year’s iGEM competition.

Shilts also has worked in the laboratory of Stevenson Professor of Neurobiology Kendal Broadie studying fragile X syndrome, a genetic condition that causes a range of developmental problems including learning disabilities and cognitive impairment. Based on a clinical finding that inhibiting proteases can treat fragile X, he genetically engineered a fruit fly to have over-active proteases, as happens in humans. Using that fly model, he identified a molecular signaling mechanism that provides a new target for therapies that can reduce the damage done by fragile X with fewer side effects than current therapies.

Through efforts like this, Shilts managed to sweep up a number of awards and honors during his four years on campus, including a Littlejohn Research Fellowship, the Barry M. Goldwater Scholarship, election to Phi Beta Kappa as a junior, and most recently, a Churchill Scholarship, which will provide him the funding to pursue a master’s degree at Cambridge University in England.

“When I look back at my experience at Vanderbilt—and compare it with the experiences of friends studying at other top universities—what strikes me is how much we have been able to push the boundaries of the undergraduate research experience,” Shilts said. “I didn’t just work on a research project under the direction of a graduate student, I got to work independently and even direct a laboratory space. I had far more opportunities to be creative and inventive than I ever expected.”