When first-year students arrived last August at Stambaugh House, a residence hall on The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons, no doubt much of what they encountered was brand new. New surroundings, new people—some even toted new clothes and dorm room accessories in newly acquired luggage. Others carried new technology—smartphones and laptop computers—ready to embark on their college experience.

But a relic from the past awaited them in the Stambaugh lobby: a refurbished jukebox, painstakingly stocked with vintage 45s from a bygone era.

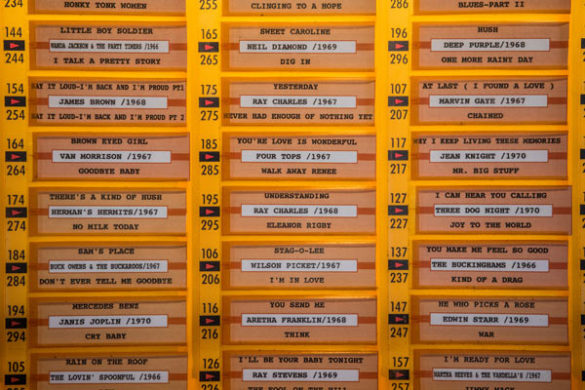

The jukebox is the brainchild of Alice Randall, faculty head of Stambaugh House and writer-in-residence in the departments of English and African American and Diaspora Studies. It is filled with music from 1966 to 1970, the years that Nashville native and noted Vanderbilt alumnus Perry Wallace was a student on campus.

Wallace is the subject of Strong Inside, Vanderbilt alumnus (BA’92) Andrew Maraniss’ award-winning biography that details Wallace’s trials as one of Vanderbilt’s first African American undergrads and the first black basketball player in the Southeastern Conference. Strong Inside was chosen as the 2016-17 Commons Reading. Established in 2010, the Commons Reading program serves to enhance the undergraduate residential experience, one of four pillars of Vanderbilt’s Academic Strategic Plan. The program promotes a communitywide dialogue about a shared text through various programs and events targeted to first-year students.

Lived experience

But how to help today’s students better understand the struggles Wallace endured when he matriculated at Vanderbilt a half-century ago? Randall turned to the universal language of music.

“That was a time of division in the country and also a time of great progress. I was trying to think about ways to make these themes a part of the lived experience of our students,” said Randall, known as “Al-Pal” to the young people in her charge. “We decided to collect songs from the time that Perry Wallace was here—songs he would have heard whether he was back at Pearl High School, or walking along Jefferson Street, or walking down Fraternity Row.”

Not only does the jukebox—a Rock-ola Supersound 2—draw visual focus in Stambaugh’s spacious lobby, it also serves as a powerful symbol of the past.

“Most of my students had never seen a real mechanical jukebox,” Randall noted. “In the 1960s, jukeboxes, like lunch counters in Nashville, were segregated. You’d have a country jukebox or a rock jukebox or an R&B jukebox. It gives these kids the lived experience of how different America was for different communities.”

The Stambaugh jukebox contains all genres of music. Randall and her husband, David Ewing, assembled it last summer on a budget, scouring warehouses throughout rural Middle Tennessee for discarded but still playable 45-rpm singles.

“We had a list of the hit songs we were interested in from each year—’66, ’67, ’68, ’69 and ’70,” said Randall, who calls the resulting jukebox “a wonderful curated soundscape.”

“There are almost 200 songs in the jukebox,” she said. “These songs are a shared text in that these particular students in Stambaugh have had access to them consciously and unconsciously throughout the year.”

Kyra Owensby, a Stambaugh resident from Huntsville, Alabama, who served as house president for 2016-17, loves the nostalgia evoked from hearing songs from the past.

“Finding an artist you’re familiar with on the jukebox and then exploring a song by them you maybe didn’t know gives you a fuller picture of what they were trying to say with their music. You get a better idea of how someone else views the world,” she said. “I feel like that’s another way to start conversation, which is one of the big things that Al-Pal is about. ‘Where the lost art of conversation is found’ is our house motto.”

Music as medicine

The jukebox has been a center point of Stambaugh Soiree, a weekly Wednesday-night gathering of all house residents for conversation and food. Quarters are doled out, and the students take turns feeding them to the machine. “It’s a wonderful way to live compromise,” Randall said. “We only get to hear a certain number of songs during the hour that we are together.”

Not only is the jukebox an instant conversation piece, it also provides a more communal experience than simply strapping on headphones and listening to music on one’s own, said Ann Huesken, a Stambaugh resident from Cleveland, Ohio. “It adds to the overall ambiance and feeling of community in the house,” she said.

Favorite songs include Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” from 1967 and Ben E. King’s 1961 classic “Stand By Me,” which predates the Wallace era but has long served as a Stambaugh House anthem. The students delight in the novelty of Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’” from 1966 and Jeannie C. Reilly’s “Harper Valley PTA” from 1968.

“One thing you notice is that struggle has been in all eras of music—that music is this sort of balm of Gilead. ‘Come on people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now,’” said Randall, reciting the chorus of The Youngbloods’ “Get Together” from 1967. “We love that song. That’s a song that speaks to the present moment, and it spoke to the Perry Wallace time period.”

Stambaugh resident Davison Thompson of Austin, Texas, agrees.

“The jukebox’s songs have themes of acceptance and tolerance that gave me a sort of full-circle moment when I walked into Stambaugh at the beginning of the year with the story of Perry Wallace still fresh in my head,” he said. “As someone who has an appreciation for R&B and soul music, but not necessarily a full knowledge of the musicians or understanding of the stories that the lyrics tell, it’s been really neat to hear the different genres mixed with songs and musicians that I already listen to, like The Beatles and the Rolling Stones.”

Maraniss, the Strong Inside author, was a guest at Stambaugh Soiree in March. “We played the jukebox and ate local hot chicken in honor of the book,” Randall recalled. “He came the day Stambaugh residents were writing notes to next year’s first-year students about what it means to be strong inside.”

Limitations of technology

The jukebox allows students to imagine a time that was less convenient and required more constancy. Today, thanks to streaming services like iTunes and Spotify, millions of songs are accessible any time of day through the click of a mouse or the swipe of a finger—but not so for students in the past.

“It’s a taste of an earlier era—realizing that a jukebox may have had the same songs on it for six months, so you get to hear those same songs through highs and lows, good days and bad days. The students are getting that experience,” Randall said.

“It engages you in a way that new technology doesn’t,” said Monica Peacock, a senior from Dakota Dunes, South Dakota, who served as Stambaugh House president four years ago and stopped by to sample the jukebox during move-in last fall. “Not only are you interacting with something that is before your time, but you’re engaging it in a more active way than you would current technology.

“I think we have a tendency as millennials to feel that any new development in technology is routine, but time moved differently in the past,” she said. “Having students really listen to the music—in many ways that’s a metaphor for listening to one another.”

The Stambaugh jukebox has experienced mechanical problems over the course of the year, requiring skilled students to pitch in and repair it.

“It almost becomes a metaphor for so many things, like it’s hard to keep up these old structures as the world changes,” Randall said. “In some ways, we like to think of our jukebox as a time machine, because it takes kids back to the musical time of ’66-’70, but also to a time when there were fewer choices; when technology was having glitches and also having expansion; when we were moving from a mechanical world into an electronic world. I think they’ve learned a lot from their jukebox.”

A simple formula

Randall, a novelist, songwriter and award-winning cookbook author, has made food, music and conversation the central themes of programming at Stambaugh House throughout her four-year tenure as faculty head. She’s employed a simple formula for building community.

Peacock recalls arriving at Vanderbilt from a “pretty homogenous” small town. “Walking into Stambaugh, where you have people not only from all over the country but all over the world, how do you make that community work?” she reflected. “[lquote]I think Al-Pal was instrumental in teaching me that it doesn’t take a lot to get people to come together and learn about other cultures. The universal language is music, it’s food.[/lquote] As long as people have something to do with their hands while they’re intermingling and getting to know one another, you can certainly build a community that way.”

The relaxed atmosphere and quality of refreshments served has made Stambaugh a destination gathering spot for students from across The Ingram Commons.

“Al-Pal goes all out, all the time,” said Minguk Seo, a Stambaugh resident from Phoenix, Arizona, who noted that Randall favors serving handmade, artisanal foods over the typical pizza and potato chips.

“She makes a point to bring in different types of food that relate to different cultures and different topics,” he said. “I think to her food represents more than just food. I think it’s a way for her to push us to have new experiences.”

Celebration and transition

At this year’s Stam Jam, the house’s signature end-of-year event, several food trucks occupied the parking lot beside Stambaugh House while nearly a dozen food-filled tables bordered its lawn. The multicultural offerings at each station represented a different life transition, as did the songs being played over a loudspeaker by a DJ from Nashville radio station Lightning 100.

“The theme of this year’s Stam Jam is ‘celebration and transition,’ because my original class of first-year students who started Stam Jam four years ago is graduating,” explained Randall, who is stepping down as Stambaugh’s faculty head at the end of the current academic year. Stam Jam likely will be retired, she said, and the jukebox will be relocated elsewhere on The Ingram Commons to make way for the new head of house and a new class of students to create their own traditions.

Randall will spend the next year pursuing several creative projects, including completing a novel, Zagging with Ziggy, set in Detroit from 1948 to 1968 that will explore themes of girlhood, self-invention and citizenship. She has been invited to collaborate with renowned writer-director-producer Reginald Hudlin on several issues of the DC Comics series Batman, and she will write and direct a short film next summer. Randall plans to return to the classroom in fall 2018.

The jukebox will live on. Strong Inside has been voted the Commons Reading for a second year in 2017-18, with discussion and programming to focus on previously unexplored characters, additional diversity themes and the role of gender in the history of Vanderbilt athletics. The jukebox also will be an enduring source of memories for the current first-year class.

“On Parents Weekend, the first thing my dad noticed was the jukebox in the Stambaugh lobby. Once he saw that all the songs in it were songs he grew up with, he dragged me over. He played The Supremes and The Beatles, and we danced around the lobby together,” remembered Sara Wright from Natick, Massachusetts.

“In Nashville, music is so key to the city,” Randall said, “and having this shared music from an earlier period has been key to Stambaugh this year.”