For the young man we’ll call Adam, cooking is more than a pastime, it’s a calling. One day, he wants to be able to live away from home and find a job as a pizza chef.

Working with him to change problem behaviors, five Vanderbilt University graduate students helped Adam, a 23-year-old with autism, move closer to his goals.

Kate Chazin and her team, all master’s students in the Department of Special Education in Vanderbilt’s Peabody College, met Adam when he was referred to the university’s Behavior Analysis Clinic (BAC) for problems with aggression and running away. Adam had recently been expelled from a day program for disruptive behavior. He lived at home with his mother.

Adam enjoyed cooking and valued independence. In talking with him and his mother during their assessment, the team saw that vocational skills were a priority for both. But although he spent a lot of his free time in the kitchen, Adam wasn’t able to follow written recipes.

An ongoing collaboration between The Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders (TRIAD) and the Department of Special Education, the BAC is an applied-training site for master’s students interested in becoming behavior analysts. The nature of its work and the caliber of the students trained there make it a valuable community service and a vehicle for important research as well. Under the guidance of BAC directors Joe Lambert and Nea Houchins-Juárez, students spend a semester at the clinic designing and carrying out interventions for challenging behavior that has resisted previous treatment. They also learn to recognize that changing challenging behavior presents a novel and critical opportunity for instruction and skill-building for clients.

In addition to Chazin, who served as Adam’s case manager, team members included Danielle Bartelmay, Sarah Reynolds, Monica Rigor, and Lillian Stiff. Working together, they helped reduce Adam’s tendency to run away and his aggressiveness to near zero. They spent the rest of their time with him teaching him to read and follow written recipes, skills that could offer a way to improve his life. Guiding Adam for two months in his home kitchen, they taught him three recipes—one for salad, one for pizza, and one for cookies—intended to represent an appetizer, entrée, and dessert. His mother was typically in the room across from the kitchen during sessions, and the team walked her through their procedures.

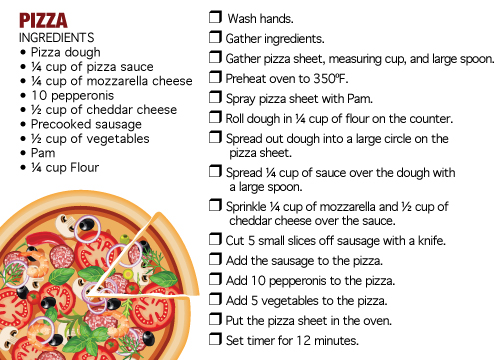

“We searched for recipes that could each be easily divided into 15 discrete steps, that didn’t require the use of sharp knives or the stove, and that Adam and his mother enjoyed eating,” Chazin says. “The steps were similar to those found in a typical written recipe but elaborated slightly. For example, where a typical written recipe might say ‘add and mix the oil and flour,’ we would create three discrete steps—add ¼ cup oil, add 1 cup flour, and mix together with spoon.

“There are two instructional techniques that people often use to teach complex tasks, forward chaining and total task chaining. In forward chaining, you teach tasks by steps. In total task chaining, you teach all the steps at once. We devised 15 steps for each recipe—which multiplied by three when we split each step into reading the step, performing the step, and checking the step off—so forward chaining would have taken at least 45 sessions. But total task chaining would have been too much to teach all at once. So, for each recipe, we grouped steps into functional units of 5 written steps, or 15 functional steps when we split each written step into read, do, and check off.”

In making a pizza, for example, the first five steps the team asked Adam to follow were “wash hands;” “gather ingredients;” “gather pizza sheet, measuring cups, and spoon;” “preheat oven to 350ᵒ F;” and “spray pizza sheet with Pam.”

The team’s work with Adam combined different strategies that had previously been used in isolation—clustered chaining, prompting through the entire task during each instructional trial, and intermittent queries to ascertain mastery and determine whether he needed further coaching.

“What was really cool was that Adam learned each new recipe faster than the last,” Chazin says. “The training was not only effective, it was efficient.”

Adam ultimately grasped all steps—45 each for cookies, pizza, and salad. He reached mastery after eight instructional sessions for cookies, four for salad, and two for pizza. For all three, he was still able to follow the recipes 3 to 6 weeks later. At the end of the study, the team created a book for him with recipes in the same format so that his mother could continue practicing new recipes with him.

Based on the results of their work with Adam, Chazin and her team reasoned that clustered forward chaining may be an effective, efficient means for teaching long tasks.

“This approach offers another way to teach vocational skills to adults with autism,” Chazin says. “I think that it can be applied not only to recipes but to any chained tasks. Cleaning, janitorial skills, cooking. A lot of jobs require chained tasks, and clustered forward chaining may be one way to teach a variety of complex skills.”

In the fall, the team presented the results of their study with Adam at the annual Tennessee Association for Behavior Analysis conference. This May, Chazin will present a paper on the study as part of a symposium at the Association for Behavior Analysis International’s annual conference in Chicago.

“Kate has a great work ethic, is approachable, is invested in teaching meaningful skills, and can solve problems,” says Lambert. “She’s exactly the type of person we want working as a case manager at the Behavioral Analysis Clinic.”

“I love being able to work with clients one on one and to see a single client all the way from assessment through intervention,” Chazin says. She hopes to study school psychology at the doctoral level and continue her research.

And Adam is so many steps closer to his dreams.