In a few months, Vanderbilt’s digital pipeline to the outside world will expand tenfold, making it much easier for campus researchers to send and receive the increasingly large data files characteristic of cutting-edge scientific and medical research.

“We are joining the 100 gigabit per second (Gbps) crowd, which includes many of the top 100 research universities around the country,” commented John McCammon, principal relationship manager for research in Vanderbilt University Information Technology (VUIT), one of the key participants in the joint faculty/staff project.

A $500,000 infrastructure grant from the National Science Foundation made the $750,000 upgrade of the campus connection from the current 10 Gbps to 100 Gbps possible. Additional support from the Office of the Provost will go toward the increased expense of operating the faster network.

To put the difference between 10 and 100 Gbps into perspective, a 10 Gbps channel can stream about 50 high definition videos at the same time without freezing and buffering, while a 100 Gbps channel can stream 500 videos simultaneously. The university and medical center have a total of 32,600 students, faculty and staff members: The 100 Gbps channel could deliver the full text of Moby Dick to every one of them at the same time in only 2.5 seconds.

Currently, the campus has two basic Internet connections. One is the original Internet. It began as ARPAnet, a computer network created by the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency to link major research universities and defense contractors. After the invention and spread of the World Wide Web, this network was rapidly coopted by the private sector so it is now called the commodity Internet. Vanderbilt has a 10 Gbps link through a hub in Indianapolis. This is the channel that students, staff and faculty use to browse the Internet, shop online, download music and videos. Peak use is currently about five Gbps.

As the original Internet became increasingly dominated by commercial traffic, however, government agencies and research universities created a second network, called Internet 2, which allowed them to exchange data with greater speed and reliability. For the last decade Vanderbilt researchers have had dedicated access to a 10 Gbps line that runs to a hub called the Southern Crossroads (SOX) in Atlanta. This hub provides access to Internet 2 and other national research networks such as the Energy Sciences Network that links the national labs, including Oak Ridge.

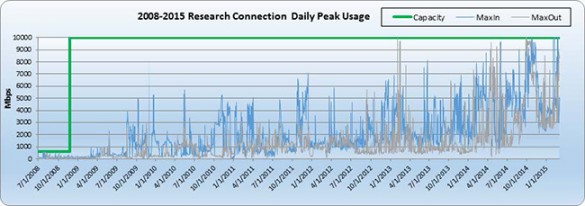

During the last few years, faculty use of this dedicated research Internet has grown considerably, led by a group of physicists who are participants at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. When it’s operating, the particle collider generates about 50 Gbps of data, which is distributed through a decentralized network. In the U.S., the raw data is sent to Fermilab in Illinois, where it undergoes initial processing and then is distributed to eight “Tier 2” centers, including Vanderbilt, where physicists analyze and interpret the data.

A year and a half ago, one of Professor of Physics Paul Sheldon’s graduate students demonstrated the limitations of the university’s 10 Gbps research connection when he ran an analysis that singlehandedly filled the pipeline for three days.

“I can’t say that he wasn’t aware of the impact of what he was doing, but the project was necessary and legitimate,” said Sheldon. Sheldon and Professor of Physics Charles Maguire led the faculty collaboration on the upgrade.

Sheldon assembled a list of 10 other Vanderbilt research communities that make extensive use of the research Internet and so would benefit from the project. They range from chemical engineering to biochemistry to genomics to epidemiology to medical imaging to crystallography. This information was submitted to the National Science Foundation as part of the successful proposal to gain its support for upgrading the university’s research Internet connection.

“We’d been aware of the availability of the NSF funding for several years,” said Dave Mathews, VUIT director of network services. “But we had to reengineer the campus network before we could take advantage of it. A lot of things had to come together and the timing had to be right.”

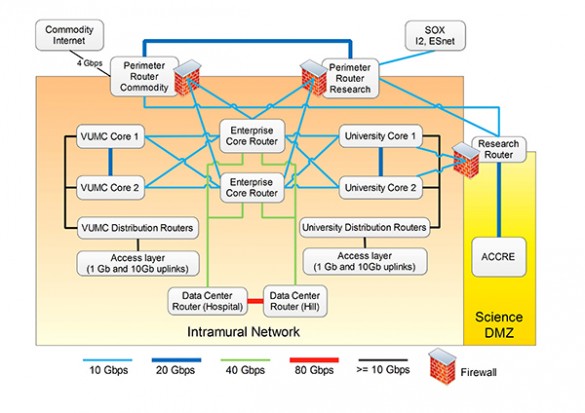

So the campus launched a two- to three-year program that included replacing campus routers, firewalls and security systems with next generation versions that increased capacity of the campus connections and helped decrease the dependency on the information managers’ geographic location on the network. The goal was for campus users to access the data and software that they have stored online from their office, lab, classroom – from any place on campus.

“The old system was particularly hard on researchers at the Medical Center because they had to work through a firewall that severely restricted the flow of information,” said Sheldon.

In the new configuration, the 100 Gbps pipeline will plug into the Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education (ACCRE), Vanderbilt’s campus-developed supercomputer, which will manage the increased traffic. ACCRE has been placed in a “Science DMZ” that is strictly controlled by special security measures designed for high-performance science environments.

“One of the things that is really cool about this project is that it truly was a joint, collaborative effort between VUIT and campus researchers which had a beneficial outcome,” said Sheldon.

“This upgrade should give our faculty the connectivity that they need for the next five years but then I wouldn’t be surprised if we’ll have to think about a further expansion,” said Mathews.