In 1914, Bruce Ryburn Payne, president of George Peabody College for Teachers, dreamed of a school unlike any other.

As the psychology and secondary education scholar looked out over the newly established campus adjacent to Vanderbilt University, with its open, grassy lawn, stately pillared buildings and sprawling esplanades, he saw more than a traditional “normal school” where teachers would earn their degrees and quietly disperse into education systems near and far.

Instead, Payne saw an academy that would work to improve life in the rural South, its economy impoverished by war. He envisioned instruction that would be egalitarian, compassionate and non-elitist—unlike peer institutions, which remained one step removed from the problems of the disadvantaged.

Inspired by education reformer John Dewey, he imagined a college where students would be encouraged to champion the educational needs of marginalized groups, experiment with new approaches to teaching and learning, and become the next generation of thought leaders and visionaries.

Payne put his vision into action, and it was tested over time by a century’s worth of social and economic upheaval, including dire financial struggles that led to near bankruptcy before a merger with Vanderbilt. But through it all, that dedication to innovation, advocacy and outreach has remained intact. Administrators, faculty and students who came after Payne have faithfully preserved his vision, and that culture of caring lives on.

Watch “A Century Past: Peabody on 21st.”

The Seeds of an Evolution

Peabody’s culture necessarily flexed and grew in response to a changing America.

In 1914, when the college moved to its current location, it was already a well-established independent school for teachers, born of an academy formed in the late 1700s when Nashville was still a frontier town. In 1867, philanthropist and business magnate George Peabody bequeathed $1 million (later upped to $2 million) to the Peabody Education Trust Fund to build a college for teachers as a means to salvage the educational system, and thereby the economy, of Southern states ravaged by the Civil War. The donated funds enabled the then-named University of Nashville to add on a state normal college, later renamed George Peabody College for Teachers, to its downtown Nashville campus.

Three years after Payne assumed the college presidency, he moved the entire operation to its current midtown location across from Vanderbilt. For the next 65 years, both institutions remained separate and independent, sharing a few resources, but mostly keeping a wary philosophical distance.

In the early days, the curriculum at Peabody reflected its original mission to uplift teacher training to benefit the South. The campus was home to a “demonstration school” where future educators practiced their craft.

Boys were taught to use tools for building and repairing, girls learned to cook food and can vegetables, and the students learned how to become better citizens of the world.

Because the South was largely rural with a large segment of its economy dependent on subsistence-level farming, the college offered a curriculum that included best farming practices to improve nutrition and increase agricultural output, along with training in home economics, industrial arts and public health. Knapp Farms, located on 300 acres near the current Nashville airport, was a thriving agricultural outpost where students raised dairy cows, experimented with farming technologies and practiced horticulture.

By the 1930s, large land-grant universities became better suited to teach agriculture-based classes, and Peabody began to drop these courses. Of the four original focus areas, only public health remained an academic priority—largely because research data were linking physical health to income and education.

Mid-Century Changes and Challenges

While Peabody College and the rest of the country spent much of the 1940s readjusting to life after World War II, the 1950s saw a resurgence of interest in the role of education for addressing the needs of marginalized populations.

A wave of outstanding applied researchers who would soon become leaders in their disciplines joined the Peabody faculty during this time. They would revolutionize the understanding of child psychology, intellectual development and disabilities, behavioral and emotional issues, mental illness, sensory-motor disorders and the relationship between these profound issues to socioeconomic deprivation.

Under pioneering child psychology researcher Nicholas Hobbs, the faculty combined insights from psychology and the emerging field of special education to begin teaching children with special needs. They proposed that many of these children did not have to be institutionalized or kept at home, as was commonly done, but instead could remain in the community, attend special academic programs, and ultimately become functioning adults.

Meanwhile, Susan Gray’s early studies of children in poverty-stricken Appalachia proved that nutrition was strongly linked to how students performed academically. Her research also revealed that children born into poverty who were exposed as toddlers to a more enriched environment—toys, books, play activities and conversation—were better prepared for kindergarten.

Her pioneering discoveries laid the foundation for the establishment of the Peabody Experimental School in 1968 (renamed the Susan Gray School in 1986 after her death). The school was the first to be recognized nationally for early intervention programs that teach typically developing children and those with developmental disabilities side by side. Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver credited Gray’s work as inspiration for the national Head Start program.

Special Education Blooms at Peabody

The research begun in the 1950s by Peabody faculty and their colleagues flourished during the explosion of social consciousness in the 1960s, an era when Americans began to buck the established mores, rejecting the idea of discriminating by gender, class, race and income.

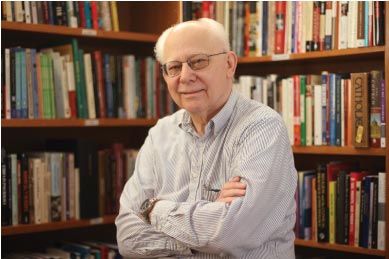

Professor Emeritus Paul Dokecki attended graduate school at Peabody 1962-65, returning to campus as a faculty member in 1970.

“Peabody had a reputation as a leader in the fields of what was then called ‘mental retardation’ and special education, but it also had its hands in many ‘War on Poverty’-related issues, which began to have a national and international impact,” Dokecki says.

Recognized as a world leader in developmental disabilities research, Peabody College was selected as one of 12 John F. Kennedy Centers in 1965. Together they formed a national network of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Centers.

Hobbs is credited as the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center’s founder, where today, medical professionals, psychologists and educators continue the cause of preventing and solving problems in human development.

“Our research gave birth to a social/cultural systemic understanding of human development problems,” Dokecki says. “Special education helped us understand better what minority kids and majority kids who were economically disadvantaged were up against.

“America’s controlling structures were closed to these kids. At Peabody, not only Susan Gray’s work, but also our work on community psychology put forth the idea that poverty itself led to great discrepancies in health services, which led to problems in developmental outcomes. And both affected a child’s ability to learn.”

Suddenly, discrepancies in educational opportunity were the focus of arguments for human rights and social justice. Peabody scholars bucked conventional wisdom, insisting that special needs children were educable, and they would figure out the means to educate them. They held firm that poverty was associated with learning deficits, and they would work to eliminate poverty. They decried the fact that subsets of the population were denied basic rights, promising to advocate for those rights.

“It was emotional courage,” says Sharon Shields, associate dean and professor of the practice in the department of human and organizational development. “It was academic courage. It was intellectual courage. It was social courage. And it was community courage.”

Peabody Grows and Merges with Vanderbilt

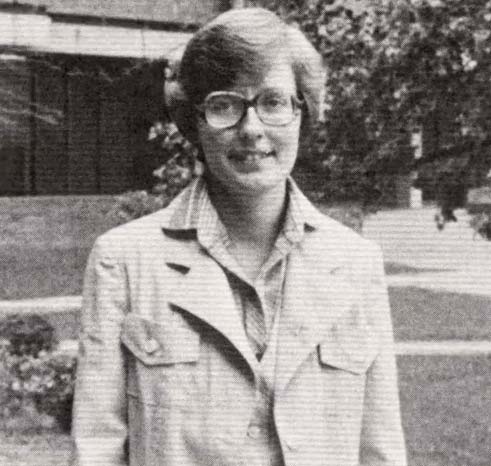

By the 1970s, Peabody College was considered one of the top academic centers for advancements in education and human development. Led by President John Dunworth, a new crop of passionate, energetic faculty members arrived on campus. Professor Emerita of Psychology Kathy Hoover-Dempsey, who arrived in 1974, was among them.

“Many of us were interested in areas like community development, education reform and new ways of approaching teaching in racially integrated communities,” Hoover-Dempsey says.

They examined educational trends and ways to prepare for the American classroom of the future, which would include a mixture of traditional white middle-class children, racial and ethnic minorities, and the offspring of immigrant parents and parents who had no education or who may have dropped out of school.

To help such parents and those whose children had behavior problems and intellectual disabilities, Nicholas Hobbs founded the Regional Intervention Program. RIP was originally designed to help parents develop loving, functional relationships with their children with autism, but it later expanded to assist parents of preschool-age children with a vast range of mental and physical difficulties. Hoover-Dempsey worked closely with Hobbs during this monumental era of education reform. “Peabody was an exciting place to be,” she says.

Shields sensed that collegial excitement on her first visit to campus. In 1974, she was a newly minted physical education teacher from Louisville, Kentucky. She had heard some of her fellow teachers bragging about their superior teacher training from the George Peabody College for Teachers, so she decided to pay a visit and see what all the excitement was about.

The moment she set foot on the campus, she says, she sensed Peabody was a place she could pursue her passion for education, equality and scholarship. Persuaded by a faculty mentor to pursue her doctorate in health and human performance, she made Peabody her home, recently celebrating her 40th year as a member of the faculty.

“There has been this genuine interest in me developing as a person, as a generative, reflective thinker and as a scholar; but also as a person who understood issues of social justice, equality and the importance of education in people’s lives,” says Shields. “The three pillars of both Vanderbilt and Peabody are teaching, community engagement and service, and research. I continually find myself at the intersection of those three things.”

As exciting as the academic research was in the 1970s, at the same time the profession of teaching was losing much of its luster. Peabody’s student enrollment declined as teaching jobs became harder to land.

The women’s liberation movement instilled in young women, who were the majority of the student body, that they could make more money if they became doctors, lawyers and corporate CEOs rather than teachers. The administration began cutting costs.

They offloaded the Peabody Demonstration School, but it made little difference. By the end of the decade, Peabody College was financially strapped.

Rumors rumbled about a merger with Vanderbilt, but it wasn’t until the middle of the spring semester of 1979 when newspaper headlines unceremoniously broke the news; Peabody College had merged with Vanderbilt University. Peabody students, faculty and staff were thunderstruck. Claiming the transition was handled sloppily and undemocratically, they rallied in protest—primarily against Peabody President John Dunworth, although Vanderbilt Chancellor Alexander Heard and his chief academic officer and president Emmett Fields didn’t escape their wrath either.

“There was a fear that if we merged with Vanderbilt, it would curtail our ability to do research that had thoughtful meaning and we’d be devoured by the Vanderbilt culture,” Dokecki says. “But realistically Peabody could not have survived without the merger. Did Vanderbilt’s traditional academic culture have an effect on Peabody? Yes. Was the effect as destructive as we thought? No. Peabody’s culture was strong enough that it still lived and was recognizable.”

Watch “A Century Past: Peabody on 21st.”

Learning to Survive—and Thrive

Even if Peabody’s unique culture survived the merger, many questioned how the college itself would function under the new parameters set up by Vanderbilt.

Peabody no longer had enough undergraduate education majors to keep the doors open. Graduate students abounded, but they rarely paid tuition. Several Peabody programs, like music and art, had been absorbed into Vanderbilt. A committee of faculty set out to create a new course of study to attract Vanderbilt undergraduates.

Under the leadership of Professor Robert Innes, the committee came up with a new major called human and organizational development, or HOD. The unique interdisciplinary program gave self-directed students the promise of learning and testing important concepts about individual, group and community growth and behaviors.

“We thought we’d be lucky if we got 25 students majoring in HOD within the first three years,” says Hoover-Dempsey, who co-taught a course with Innes. In fact, HOD was successful beyond their wildest dreams. Within a few years it became the most popular major at Peabody, and is now one of the most popular majors at Vanderbilt. Around 200 students—drawn to a program that facilitates a wide range of career pursuits—graduate with a major in HOD each year.

HOD coursework is geared toward students who care about the complex issues of the world and want to make an impact on society. Classes require that students go into the field to work on projects, and the program has one of the most rigorous internship requirements in the country.

This bent for service learning makes the program attractive to Vanderbilt students, many of whom seek to not only build a career, but also make a difference in society. In fact, they’ve been accepted into the university for just that reason.

“Vanderbilt is looking for exceptionally accomplished young people in whom we see the potential to make both Vanderbilt and the world a better place,” said Douglas L. Christiansen, vice provost for university enrollment affairs and dean of admissions and financial aid at Vanderbilt. “In selecting these students, we often seek scholarship, accountability, honesty, discovery, civility, celebration and caring.”

Adds Hoover-Dempsey: “The faculty have faith in these students to change the world.”

This entrepreneurial drive and altruistic energy is just one of the many post-merger effects that has elevated Peabody to its current status.

Peabody is consistently ranked as one of the top education schools in the country.

Its world-recognized faculty tackle even deeper societal issues, including autism, the value of pre-K education, mentoring at-risk children, urban poverty, childhood depression, charter schools, education policy, food deserts, global education and much more.

It’s easy to imagine that the early educators who shaped Peabody College over the last 100 years would be proud of the academy that exists today, Shields believes.

“I’ve been asked what Peabody will look like 100 years from now, and I can make one guarantee,” she says. “Whatever is going on in education, Peabody College will help craft the vision, live the vision and develop the next vision. I’m not worried at all. In fact, I’m very optimistic about it.”