Will revelations of the human genome finally extinguish the foul ember of racism, or will they ignite an even more insidious prejudice?

That question was at the heart of two very different conversations at Vanderbilt University this month.

On May 5, Princeton University President Shirley Tilghman, began her Discovery Lecture, “The Meaning of Race in the Post-Genome Era,” by recounting how science has been used to justify racism and other forms of discrimination.

Even though we now know that “at the level of the genome, we’re 99.9 percent identical to one another,” said Tilghman, a pioneer in the field of mammalian genetics, “. . . what I worry most about are the unintended consequences” of research.

“I worry what can happen if . . . studies . . . suggest this group of people has a genetic predisposition to obesity, for example, and that investing in their health care is not a good investment of public dollars,” she said. “We’ve seen it too many times in history where even great scientists have contributed to horrible outcomes.”

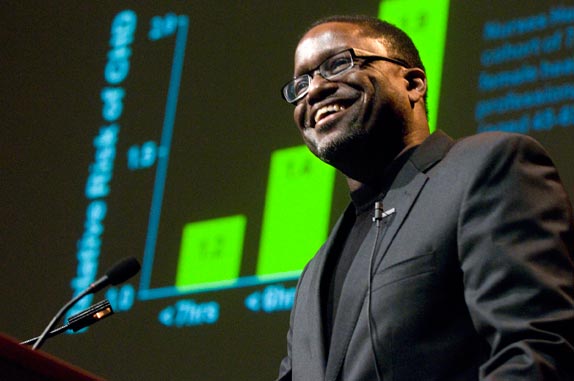

A day earlier, Gary Gibbons, chair of physiology and director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, described how the disproportionately high risk of heart disease and stroke among African-Americans results from interactions between genes and the environment.

There is emerging evidence that poverty, stress, poor diet, lack of exercise and chronic sleep deprivation can alter the expression of certain genes in ways that affect blood vessel function and structure and which predisposes to disease.

These “epigenetic” changes are not racial destiny. They can be modified.

“That’s part of our challenge,” Gibbons said. “We probably should be doing more outside of the walls of the clinic if we’re going to take care of the whole patient.”

Gibbons gave the 2011 Dolores C. Shockley Lecture, which honors the first African American woman in the nation to receive a Ph.D. in pharmacology and the first to chair a Department of Pharmacology at an accredited medical school, Nashville’s Meharry Medical College.

The annual lecture is given in conjunction with the Shockley Partnership Award, which recognizes partnerships that lead to “transformative opportunities” for minority scientists.

This year’s winners were Habibeh Khoshbouei, an assistant professor at Meharry, and her mentor, Lee Limbird, a former Meharry faculty member who currently is a professor of biochemistry and dean at Fisk University.

In accepting the award, Limbird, former chair of pharmacology and former associate vice chancellor for research at Vanderbilt, noted the “shocking underbelly of lack of equity and disparities” in American society.

“Every two minutes, a black child is born into poverty,” she said. “Every hour, a black baby dies before his or her first birthday. It’s better than that in the countries of the continent of Africa.

“The door (to education and opportunity) has to open wider,” Limbird urged her audience. “Those of you who have a grasp on the handle of that door or who have any influence in pushing that door open, open it wider.”