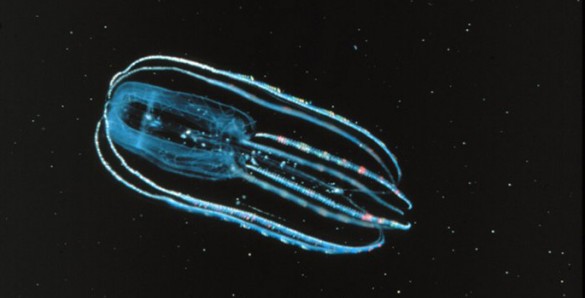

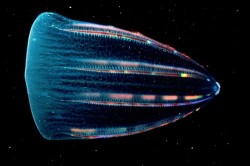

With their intricate, translucent shapes and elaborate bioluminescent displays, comb jellies add beauty and mystery to the ocean depths.

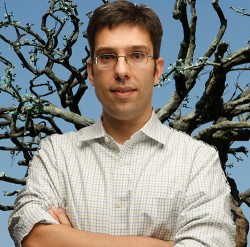

According to Antonis Rokas, these delicate marine predators – whose scientific name is Ctenophora, which is pronounced tee-na’-for-ah’ – also have an important story to tell about the origin of animals that dates back 550 million years.

Writing in the Dec. 13 issue of the journal Science, the Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Biological Sciences reflected on the significance of the first successful sequencing of the genome of a ctenophore: Andreas Baxevanis at the National Human Genome Research Institute and his colleagues have sequenced the genome of the sea walnut, an aggressive species that invaded the Black Sea in the 1980s, moved into the Caspian Sea in the 1990s and since then has spread throughout the Baltic and Mediterranean basins.

Based on an analysis of the sea walnut genome, Baxevanis’ group has come to the controversial conclusion that ctenophores are the oldest relative of the entire animal family, including humans. If true, Rokas said this conclusion radically changes our view of what the ancestor of all animals was like. After all, ctenophores have rudimentary muscle and nerve cells, suggesting our ancient ancestor could sense and move.

However, this conclusion directly conflicts with several other genetic studies that have grouped ctenopores and jellyfish together and fingered sponges as the oldest animal relative despite their sedentary nature.

Rokas, who has studied why a number of well-supported phylogenetic studies attempting to map the tree of life have come to contradictory conclusions recently, points out that this conflict is not surprising. The branchings that gave rise to the lineages that eventually became the sponges, ctenophores and jellyfish took place in a narrow window of time a long time ago. These are the very conditions that are most difficult to map correctly.

Despite these uncertainties, the addition of the ctenophore genome to existing knowledge of the earliest animals and their closest relatives has a powerful lesson to teach, Rokas said. By demonstrating that these ancient species were gaining and losing genes and even cell types independently, it should finally put an end to the outmoded but persistent notion that early animal evolution took the form of a straight-line path from the “simple” to the “complex.”

Rokas’ perspectives essay in Science is titled, “My Oldest Sister Is a Sea Walnut?” More information about his research on conflicting phylogenetic studies can be found in “Untangling the tree of life.”

None of us can choose our relatives. But, if I could, I would definitely pick a ctenophore over a sponge.