(This article originally appeared in the May 11, 2012 issue of Fermilab Today. Reprinted with permission.)

Have you ever noticed how cooking oil flows on a hot pan? Unheated, the oil is thick and spreads slowly, but on a hot pan it splashes and almost looks like water. Physicists call this difference one of viscosity: Cold oil has about ten times the viscosity of hot oil.

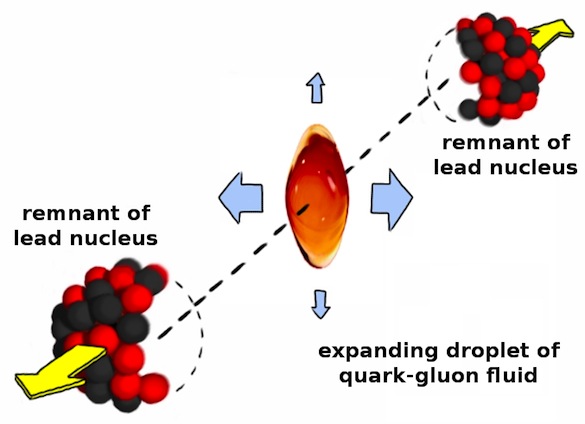

When lead nuclei collide in the Large Hadron Collider, they form an exotic fluid of quarks and gluons that flows like a liquid, except that it has no measurable viscosity.

All liquids and gases in everyday experience are made of molecules or atoms that swarm and collide with one another. The plasma in the sun is made of ions rather than whole atoms, which causes it to flow in strange and complicated ways. For a brief moment after the collision of two lead nuclei in the LHC, quarks and gluons mix as a fluid made of the smallest particles known.

To measure this fluid’s viscosity, scientists use a technique similar to splashing oil on a pan to see how fast it spreads. Cold oil tends to smear out in a circle regardless of how it is thrown, but hot oil splatters in the direction that has the greatest initial difference in pressure. Similarly, a quark-gluon fluid with initial pressure differences would spread out in a circle if it were viscous, but not if it were runny.

The droplet of quark-gluon fluid has these pressure differences because of the way that it is made. Most nuclei don’t collide head-on, but are a little bit offset when they hit each other. The collision takes a bite out of each nucleus as it flies by, and the part that collides and liquefies is shaped like the overlap region: taller than it is wide (see figure above). This asymmetry causes the drop to burst outward on each side more than top to bottom.

In a recent paper, Compact Muon Solenoid collaboration scientists [including Julia Velkovska, associate professor of physics, research associate Michael Issah and graduate students Eric Appelt, andShengquan Tuo] measured the shape of the flow of the quark-gluon fluid. It acts like a cohesive liquid, but one with zero or nearly zero viscosity. Superfluids such as helium have this strange property when they are cooled to nearly absolute zero, but the droplet of quark soup is hundreds of thousands of times hotter than the center of the sun, the temperature of the first microsecond of the Big Bang.

Jim Pivarski, Fermilab Today