Twenty-five years ago on Dec. 10, King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden presented the Nobel Prize to Vanderbilt biochemist Stanley Cohen for his discovery and characterization of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and its receptor.

At the time, the implications of Cohen’s discovery two decades earlier had barely begun to be realized.

Today the EGF receptor is the target for a growing number of cancer drugs. Families of EGF-like proteins and their receptors also are being studied for their potential role in preventing heart failure and bowel damage, slowing the progression of kidney disease, and promoting liver regeneration.

Cohen, 89, who is retired and lives in Nashville with his wife Jan Jordan, passed up an offer to be interviewed for this story. But his former colleagues at Vanderbilt said the significance of his findings cannot be overstated.

These discoveries “paved the way (for) the finding of treatments targeted to this receptor and related molecules in a number of cancers such as lung, breast, head and neck, and gastrointestinal malignancies,” said Carlos Arteaga, who directs the Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer in the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

“The discovery of mutations in this receptor has revolutionized the care and outlook for many thousands of lung cancer patients worldwide,” agreed David Carbone, director of the SPORE in Lung Cancer.

“Targeting this receptor in lung cancer tumors expressing this mutant protein has led to dramatic tumor responses and often rescues the patient from near-death with a ‘Lazarus’-like effect,” he said. “[rquote]There are few discoveries that have so transformed clinical care as this one has.[/rquote]”

Serendipity

Cohen is the second Vanderbilt faculty member to win the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. The late Earl Sutherland was honored in 1971 for discoveries related to cellular signaling and hormone action.

Like many scientific advances, Cohen’s was serendipitous.

In the mid-1950s, Cohen was working at Washington University in St. Louis with Rita Levi-Montalcini, who discovered nerve growth factor, when he stumbled upon another factor that stimulated epidermal growth and caused baby mice to open their eyes earlier than normal.

After joining the Vanderbilt faculty in 1959, Cohen isolated EGF and with Graham Carpenter, professor of biochemistry, characterized its receptor.

Cohen and Levi-Montalcini shared the 1986 Nobel Prize for their discoveries. “Many new things are found by accident,” he told a group of high school students in 2007. “If you’re prepared to see the accident, you can find it.”

In 1985, Robert Coffey was considering a move from the Mayo Clinic to Vanderbilt when he met with Cohen and asked if a person with a medical degree like him “could accomplish anything worthwhile in the lab.”

“He looked at me,” Coffey recalled, “cupped his hands over his eyes (his characteristic focusing gesture, I was to learn), and said, ‘Yes, if you do two things. One, pay careful attention to your data and, two, be lucky.’ This was the best scientific advice I ever received.”

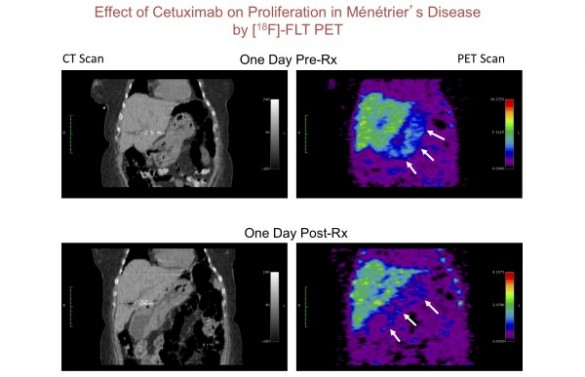

Coffey joined the Vanderbilt faculty in 1986 and went on to discover that a drug used to treat colorectal cancer, by blocking the EGF receptor signaling, can reverse Ménétrier’s disease, a rare, debilitating stomach disorder.

Today Coffey is co-director of the SPORE in Gastrointestinal Cancer and directs the Epithelial Biology Center. Vanderbilt’s three SPORE grants are funded by the National Cancer Institute.

Epitome of a scientist

“Dr. Cohen’s discoveries have led to current clinical trials where EGF-family growth factors (like neuregulin) are being tried as treatments for heart failure,” said Doug Sawyer, chief of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine. “Growth factors in the EGF family and receptor tyrosine kinases in the EGF receptor family are now recognized as critical regulators of not only cardiac development, but also the maintenance of the adult heart.”

There’s also increasing evidence in animal studies that the EGF receptor pathway may be involved in progressive kidney diseases, including those associated with high blood pressure and diabetes, added Raymond Harris, chief of the division of nephrology and hypertension. Blocking EGF signaling could lead to new treatments for these diseases, he said.

Cohen “is really the epitome of a scientist,” Harris said, “to be focused and committed and to follow the science wherever it goes … (He) really has been a beacon for me throughout my research career.”

While much progress has been made, much remains to be learned, Carbone said.

Lung tumors eventually become resistant to drugs like Iressa and Tarceva that target the EGF receptor. Fortunately, researchers have been able to find ways to circumvent these “resistance mechanisms,” he said, “and these patients are experiencing second responses to these new therapies.”“This is a great example of how basic science can lead to candidate therapeutics, but also, importantly, how clinical information can inform basic science studies to understand why one patient’s tumor responds to a drug and another doesn’t,” Carbone continued. “This new information then comes back to the clinic to influence selection of patients for targeted therapy.”

Cohen’s contribution “is emblematic of the benefits of discovery science,” agreed William Pao, director of Personalized Cancer Medicine. “Stories like this exemplify why we must as a nation continue to invest in scientists who examine natural biological processes in life.”