When Ithaca College welcomed its latest class of incoming students this August, it was in many ways like the start of any other school year. Roused from the last sleepy days of summer, the 6,600-student liberal arts college and surrounding town of Ithaca, New York, brimmed with hundreds of new faces, each looking ahead with nervous anticipation. And yet there was something different this time around, too—an expectancy that went beyond standard freshman jitters.

One might say the entire Ithaca College community was collectively holding its breath.

The college was, and still is, at a cultural crossroads of sorts, following a series of recent Black Lives Matter protests on campus and the retirement of its president, Thomas Rochon, earlier this year. Like many schools across the country dealing with similar unrest, Ithaca has had to face tough questions about where it stands on issues surrounding diversity, equity and inclusion, and the answers have not always come easily.

When it was time to choose a new president—the ninth in the private college’s 125-year history—the board of trustees took the critical step of hiring a leader with a better understanding of these issues than most: Vanderbilt alumna Shirley M. Collado, BS’94, who among her accomplishments co-founded Liberal Arts Diversity Officers, a national consortium that promotes advancement of diversity, equity and inclusion in support of academic excellence at liberal arts colleges.

Previously the executive vice chancellor and chief operating officer at Rutgers University–Newark, Collado represents a distinct departure from earlier presidents at Ithaca. For one, she is the first person of color to head the college—in fact, she is the first Dominican–American in the history of higher education to lead any four-year institution.

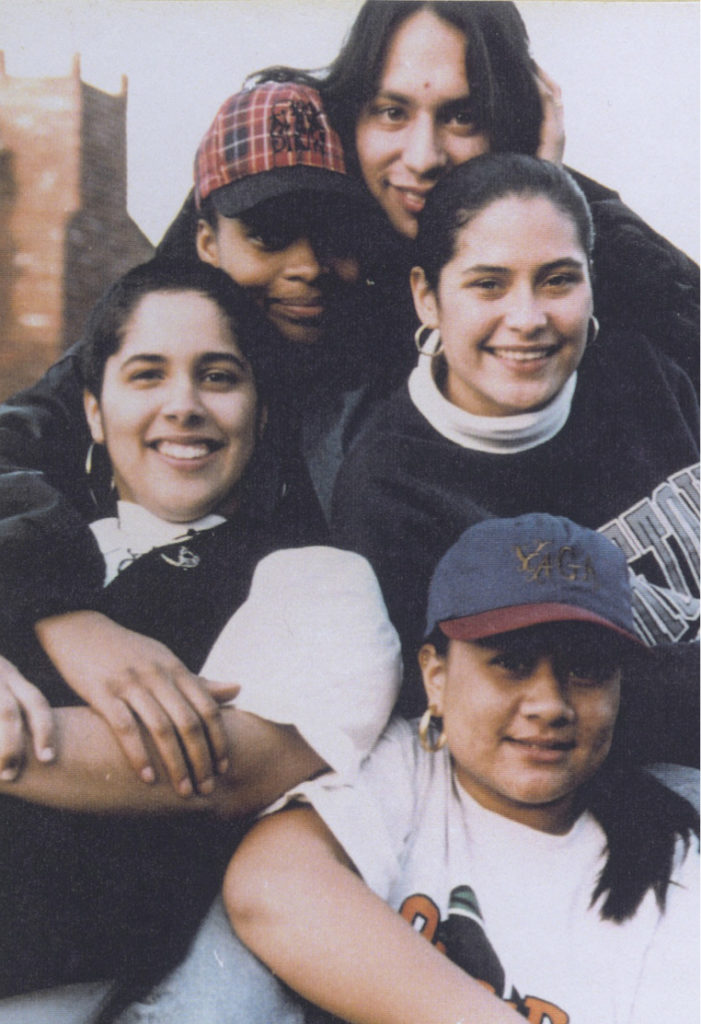

And her own college experience sets her apart as well. She was a first-generation college student when she arrived at Vanderbilt in 1989 as part of the inaugural cohort of Posse Scholars, later becoming the first from that college-access program to earn a doctorate (from Duke University) and serve as a trustee at a university—on Vanderbilt’s Board of Trust, where she has provided counsel on important higher education matters, including diversity.

“I’ve been part of many firsts in my life, and I’m proud of those accomplishments,” says Collado, a Brooklyn, New York, native whose parents immigrated from the Dominican Republic. “But at the same time, I can see how these moments in history are connected to the fear some are experiencing in America. As a nation we’re still struggling with what all of this means.”

A STAKE IN THE CONVERSATION

The struggle Collado alludes to—the age-old conflict over equality that has dogged this country from its founding—took a particularly dark turn just a few weeks into her tenure. A “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which was ostensibly a protest against the removal of a statue honoring Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in one of the city’s parks, became confrontational and violent, embroiling the nearby University of Virginia in the conflict. Collado was quick to issue a message expressing Ithaca College’s solidarity with UVA and condemning the white-supremacist violence, but the events in Virginia shook her nonetheless.

“What happened in Charlottesville had a sobering effect on me,” she says. “It reminded leaders like me that our institutions are microcosms of the forces that exist on a global scale. We can’t afford to continue thinking we’re ‘colleges on a hill.’ The world is with us, whether we like it or not.”

If anything, the events in Charlottesville showed why the intersection of identities on college campuses matter now more than ever, not just in terms of race and ethnicity but in other areas as well, like gender and sexuality, religion and immigration status. In the ongoing struggle against bigotry and closed-mindedness, higher education is on the front lines, but its defenses are only as strong as the community of learners behind it. Without diverse perspectives to draw upon, our understanding of the world is greatly diminished, leaving institutions ill-equipped to solve society’s most complex problems.

“I’ve always been deeply honored that Shirley chose Vanderbilt as part of our inaugural Posse class. We are a better and stronger university because she took that leap of faith and because of her continued leadership and service to the university,” says Vanderbilt Chancellor Nicholas S. Zeppos. “Shirley is a facilitator, a consensus builder and a brilliant leader. Higher education as a whole stands to benefit from the example I know she will set at Ithaca.”

For her part, Collado is intent on addressing divisive topics head-on before they can metastasize. As The New York Times reported this summer, one of her first initiatives as president was to form “intergroup dialogues,” in which students, faculty and staff talk through these difficult issues together. Whenever possible, she tries to be in the mix of these dialogues, fostering the discussion.

“It’s important for the stakeholders in this community not to let go of these tough conversations,” she explains. “We have to lean in to these really difficult moments so that students don’t just compartmentalize what they’re witnessing going on in the world, but rather activate the humanity and social change needed to solve these daunting national problems.”

If this sounds a bit like a campuswide therapy session, there is a good reason for that. Collado earned both a master’s and Ph.D. in clinical psychology from Duke University, where she specialized in trauma among multicultural populations at the intersection of race, ethnicity and gender. She also has years of experience teaching related subjects at several colleges and universities, including New York University, Georgetown University, George Mason University, the New School, Middlebury College and Lafayette College.

While some might dismiss these intergroup dialogue sessions as simply an exercise in political correctness, Collado makes a persuasive case for having them. Tough conversations surrounding issues of difference are happening regardless, and for meaningful discourse to take place there needs to be a proper forum, she says. That means everyone has a seat at the table and all voices are heard, not just those of the underrepresented segments of the student population but those of the majority white, middle-class and more affluent students as well.

“I want every student, faculty and staff member to feel like they have a stake in the conversation regardless of their background or belief system,” she says. “There’s a large group in this country that’s really grappling with these issues of identity. Many of them don’t even know how to enter into the conversation in a way that’s healthy, humane or thoughtful, and as educators we have to fix that.”

THE POWER OF EDUCATION

One of the reasons Collado says she accepted the job at Ithaca was that she was “drawn to the challenge of it,” given the important changes happening not just on its campus but nationwide, too. But Ithaca also offered her something equally compelling: a chance to be part of an institution that shares many of the same qualities that made her own Vanderbilt experience so transformative.

“Like Vanderbilt, Ithaca is committed to the liberal arts and to the power of professional education, and there’s a real focus here on undergraduates living and learning together,” she says. “I care deeply about all those things.”

Collado, who double-majored in human and organizational development and psychology at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College and was named the school’s Distinguished Alumna in 2015, credits her own undergraduate experience with broadening her horizons and informing her life’s work.

“I have many fond memories of being a student at Vanderbilt, and I learned some hard things there, too. It wasn’t all joyous,” she explains. “But even those experiences were a gift. Had I not been at a university that—let’s be honest—wasn’t originally intended for someone like me, I wouldn’t be able to see things the way I do. I’m a better leader because of it.”

Collado’s leadership skills also have benefited from years of management experience in higher education and the nonprofit world. At Rutgers University–Newark in New Jersey, she oversaw academic affairs, student affairs and core institutional operations in her aforementioned role as executive vice chancellor and chief operating officer. She also served as vice president for student affairs and dean of the college at Middlebury College in Vermont, and before that as executive vice president of The Posse Foundation, where she helped expand the footprint of the organization that led her to Vanderbilt in the first place.

Posse recruits talented, high-achieving students from urban high schools, like the one she attended in Brooklyn, and sends them in groups, or “posses,” to top colleges and universities around the nation. Vanderbilt was the foundation’s very first partner institution 28 years ago; today there are 57 nationwide.

“Shirley is superbly prepared to lead Ithaca College,” says friend and colleague Freeman Hrabowski III, the long-serving president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and former chair of the President’s Advisory Commission on Educational Excellence for African Americans under President Obama. “She has been a very successful educator and administrator in a variety of positions at different types of institutions. Most important, she understands from firsthand experience the power of education to transform lives. Ithaca is very fortunate.”

IMPACT ON VANDERBILT

Ithaca College, however, is not the only higher-ed institution currently availing itself of Collado’s expertise. Her knowledge and experience are making a difference at Vanderbilt, too. An officer and trustee on the university’s Board of Trust, she chairs the group’s Academic and Student Affairs Committee and is a member of its executive and campaign committees.

“Shirley’s expertise and commitment to ensuring a high-quality education is accessible to every talented student is widely apparent in her leadership as a trustee,” says Bruce R. Evans, BE’81, chairman of the Board of Trust and managing director of Summit Partners, a growth equity, venture capital and credit investment firm. “She’s the quintessential community builder—always bringing together diverse perspectives to find new opportunities for Vanderbilt.”

Building such communities is no easy task, Collado concedes—be it at Vanderbilt, Ithaca, or any other institution with a long, complicated history. But she takes heart from the positive changes that have occurred at her alma mater just within the past few years, such as the establishment of Vanderbilt’s Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, and she hopes to follow the lead of Chancellor Zeppos as she undertakes similar initiatives at Ithaca.

“Nick is doing transformative work,” she says. “His decisions may not always be popular with everyone, but I think history is on his side. All college presidents need to be making these courageous moves to push the needle forward.”

Ultimately, the biggest question facing higher education is one of identity, not just the individual identities of those expectant faces who arrive on college campuses every year—faces that increasingly are reflecting the diversity of the wider world—but the identity of the institutions themselves. As much as higher education prides itself on being a bastion of tradition, its institutions must be forward-thinking as well, keeping pace with the changes in society and, whenever possible, getting out ahead of them to lead by example.

“It’s a harder question than just recruiting a diverse student body. You have to infuse diversity, equity and inclusion into all aspects of what you do as an institution,” Collado explains. “We’ve reached a critical mass in the country where this is now the expectation, and it’s not just students of color asking for it. There are also plenty of white students who expect to be going to institutions that will help them develop competencies and skill sets that will make them critical agents in the workforce and society.

“They can’t do that if they’re only able to see the world from one vantage point.”

Thomas-Hunt Appointed to Strengthen Vanderbilt’s ‘Inclusive Excellence’

Melissa Thomas-Hunt, Vanderbilt’s inaugural vice provost for inclusive excellence, sees a big part of her new role as breaking down the traditional notions of diversity.

“I think a lot of times when people hear the word diversity, they think there are groups of individuals who are part of diversity and those who are not,” she says. “But diversity encompasses everybody—the entire fabric.”

Thomas-Hunt, who came to Vanderbilt from the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, was appointed July 1 by Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Susan R. Wente to build on the efforts already underway at Vanderbilt to create a welcoming environment for students, faculty and academic staff, and to help advance equity, diversity and inclusion in the trans-institutional research and education missions of the university.

The “inclusive excellence” portion of her title echoes remarks Chancellor Nicholas S. Zeppos first made in fall 2016, when he asked faculty to take stock of the strides Vanderbilt had achieved in terms of creating a more inclusive learning environment, and challenged them to look forward.

“What does our community look like? How do we invite people into our community? What are the structural, physical and psychological barriers in our environment?” Zeppos asked the assembled faculty. “We have to be intentional in these efforts.”

Thomas-Hunt says responding to this challenge is an ever-evolving task, but one that will make Vanderbilt a richer, more productive place.

“Vanderbilt is a phenomenal educational institution, so it’s really important to put front and center that we’re always thinking about excellence,” she says. “The ‘inclusive’ piece is the piece that says the more we welcome people who bring a diversity of perspectives, experiences, backgrounds and political views, the better we can leverage those attributes to create an academic environment that’s going to allow individuals to excel as well as allow the university to continue to be at the forefront of the educational landscape.”

With an undergraduate degree in chemical engineering from Princeton University and her master’s and Ph.D. from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, Thomas-Hunt held faculty positions at the business schools of Washington University in St. Louis, Stanford and Cornell before arriving at the University of Virginia’s Darden School. There she served as senior associate dean and global chief diversity officer.

Thomas-Hunt’s research and teaching interests have focused on conflict management, negotiation and inclusive leadership within global teams and organizations. She spent numerous years teaching negotiation to executives and served as faculty leader for The Women’s Leadership Program at the Darden School.

In addition to her appointment as vice provost for inclusive excellence, Thomas-Hunt is a professor of management at Vanderbilt’s Owen Graduate School of Management. Her current research centers on the effects of status and power on negotiation processes and outcomes, as well as the evaluation and integration of expertise within diverse groups.

—KARA FURLONG