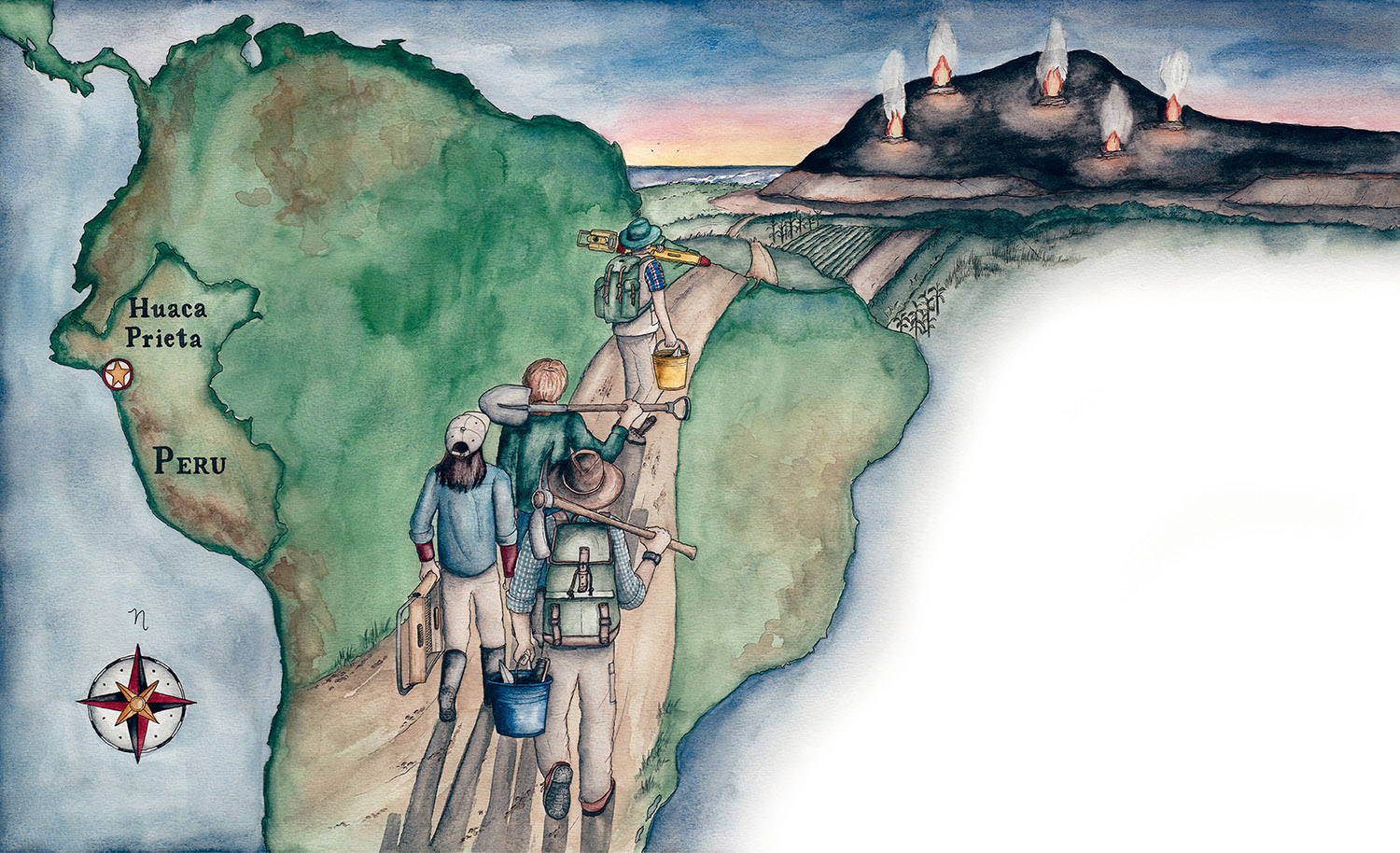

About 7,500 years ago a construction project of almost unfathomable scope began taking shape along the Pacific coast of what is today northern Peru. Initially a low-lying ceremonial mound, it would become in 4,000 years’ time a monument of staggering size—100 feet tall, 320 feet long and 180 feet wide—as generations of builders amassed untold layers of rock, soil, shell, plant and animal bone on its heights and dug numerous tombs for human burials in its depths, all without the benefit of the wheel or beasts of burden.

Meanwhile, countless ritual fires burned on its expanding slopes, the charcoal and ash accumulating until the mound grew distinctively dark. The color eventually would give rise to the name it bears today: Huaca Prieta, or “Black Pyramid.”

The name is fitting for a site that has long been shrouded in mystery, confined largely to the shadows of history since being abandoned more than three millennia ago. Archaeologists only began excavating Huaca Prieta in the 1940s, and even then much about it remained a secret. It wasn’t until 2006 that the site was first studied in great detail by an interdisciplinary research team headed by Tom Dillehay, the Rebecca Webb Wilson University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, Religion and Culture at Vanderbilt, and the late Peruvian archaeologist Duccio Bonavia.

“Huaca Prieta is a complete enigma,” says Dillehay, whose team includes more than 50 international experts, including several from Vanderbilt. “It’s the only complex coastal archaeological site in the world, and it’s one of the earliest nondomestic ceremonial structures in the Americas.”

Through years of groundbreaking research, the team has unearthed new clues about the mound’s past, which is chronicled in Where the Land Meets the Sea: Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru (2017, University of Texas Press), a soon-to-be-released book edited by Dillehay. But most important, their findings—including the oldest collection of corncobs, husks and stalks ever found and the earliest known example of indigo dye—have begun to put a face on one of the world’s longest-lasting human occupations, whose origins date back to the late ice age.

“Huaca Prieta’s significance is global,” Dillehay writes in his book.

ENVIRONMENTAL FORCES

At first glance the Peruvian coast, which is mostly desert, seems like an unlikely place for a civilization to spontaneously take root, but that is precisely what happened nearly 8,000 years ago. When construction of the mound began, the area was becoming one of the so-called cradles of civilization, joining just a handful of places around the globe like the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia. But unlike these other locations, Huaca Prieta had a clear advantage.

“Peru is a unique place geographically,” explains Dillehay, who has spent 40 years studying archaeological sites all along South America’s Pacific coast. “The Humboldt Current that comes up from Antarctica runs right up against the shoreline, and the continental shelf drops directly off. So you get this high abundance and high diversity of seafood. Because of that, it’s the only place among those pristine civilizations where there was a strong maritime economy.”

In addition to the ocean, the nearby Chicama River, which is fed year-round by snowmelt from the Andes Mountains to the east, provided an oasis of sorts for the earliest inhabitants along the coast. Drawn by these natural resources, people first began occupying the site some 14,000 years ago—thousands of years earlier than previously thought, according to radiocarbon dating conducted by Dillehay’s group.

Evidence excavated from ancient trash heaps, known as middens, shows that these late Pleistocene foragers and hunters survived on local plants, such as wild avocado, squash, beans and chili peppers, as well as shellfish, fish, and larger marine animals like sea lions, which were easy prey when stranded by the ocean’s low tide.

To get an idea of what the environment was like over the arc of human development at Huaca Prieta, Dillehay invited Steven Goodbred, professor and chair of Vanderbilt’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, to join his research team. Goodbred studies the relationship between humans and depositional landscapes—places like river deltas, where floods are frequent. His work often takes him to Bangladesh, a far more humid environment on the other side of the world, where conditions for preservation are not nearly as ideal as they are in Peru.

“The preservation at Huaca Prieta is phenomenal,” he says, noting the benefit of the coast’s arid climate. “If it were a wet environment, that mound would have been degraded and covered in vegetation long ago.”

Goodbred worked mainly along the Chicama River, where erosion had exposed layers of soil dating back several millennia. Using an auger to drill even farther, he was able to get core samples that offered a comprehensive picture of the site stretching back to the last ice age.

What he found is that the north coast of Peru experienced several significant environmental changes during the mound’s construction. Among them was a rise in sea level, prompted by retreating glaciers worldwide, which helped create biodiverse lagoons near the river’s mouth. Another was a series of El Niño floods, which deposited thick layers of silt throughout the Chicama Valley. This rich, arable silt would play an important role in agriculture later on.

“You’ve got this beautiful sequence of changes from desert pavement to river bed to lagoon to wetland to flood plain,” Goodbred says. “It was amazing working out the radiocarbon ages because each transition period in the mound construction corresponded to one of these transitions in the environment.”

CONVERGING EVIDENCE

Of all the enduring mysteries surrounding Huaca Prieta, the most compelling ones concern the people themselves: Just who were the builders? And where did they come from?

Junius Bird, the archaeologist who first excavated the site in the 1940s, was able to answer the first question to some degree. The human remains and artifacts he recovered, which are now housed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, reveal a complex culture that practiced burial rituals and produced stylized art, including elaborate textiles, pyro-engraved gourds with geometric designs, and sculpted, mineralized mud figures.

Newer findings by Dillehay’s team have helped fill in this picture even further. In fact, one weaving discovered last year revealed the world’s first known use of indigo dye, dating back 6,000 years.

Moreover, the remains of cultigens, like beans and squash, point to an evolving economy that relied increasingly on agriculture. Most notably, Dillehay’s team found the world’s earliest-known collection of corn macroremains (e.g., stalks and cobs), which included all early varieties of the plant—ceremonial popcorn, corn used for chicha beer, flour corn, and corn for foraging animals. The presence of the plant, which originated in what is today Mexico, suggests that Huaca Prieta was an important hub in an extensive trading network.

“Huaca Prieta represents some of the first beginnings of Andean civilization in several ways,” Dillehay says. “One, dispersed communities gave their collective labor to the building of a religious structure. Two, we have no households or burials or anything indicative of somebody being socially elevated above anyone else. It was an egalitarian society—you see that pretty much throughout the prehistory of Peru until about 1,800 years ago. And last, there was this multicomponent economy that kicked off civilization there—it was maritime and agricultural, with a touch or two of animal husbandry.”

But just where the people of Huaca Prieta came from originally has been a nagging question for decades. Specifically, scientists would like to know to which haplogroup—a group sharing similar genetic lineage—they belonged. If genetic material found at Huaca Prieta could be tied to any of the already identified haplogroups, or to an entirely new group, it would have important implications for the history of the Western Hemisphere.

To answer this question, Dillehay enlisted the help of Tiffiny Tung, an associate professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt whose research centers on another ancient Peruvian civilization known as the Wari. Not having any preconceived notion of what they might find, Tung and former Vanderbilt postdoctoral student Brian Kemp extracted DNA from the teeth of several individuals who had been buried at the site. Some came from remains that Dillehay’s group had unearthed, while others were from Bird’s collection at the American Museum of Natural History.

“We knew going in that it would be really challenging,” Tung says. “To obtain ancient DNA is difficult, especially when you’re talking about something this old.”

Encased in protective enamel, teeth provide scientists with the best opportunity for recovering DNA. But unfortunately for Tung and Kemp, the samples they retrieved offered only inconclusive results. They were too degraded, both because of their age and because of their exposure to salt in the coastal air—a known inhibitor to DNA amplification. A team led by Cecil Lewis, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, also analyzed the samples for independent confirmation, but they too were unable to extract endogenous DNA.

“When you hit the wall, it forces you to innovate and come up with other strategies,” Tung says. “I can guarantee you that we’ll keep trying. In a few years there could be a new technique that is better able to get the DNA. And with the new ancient DNA lab currently under construction for [Vanderbilt Associate Professor of Anthropology] Jada Benn Torres, we’ll have that chance to try again very soon.”

Teeth from the human remains at the site, however, did impart some critical information to fellow team member Larisa DeSantis, assistant professor of Earth and environmental sciences at Vanderbilt. DeSantis typically studies the teeth of megafauna—particularly large extinct animals like saber-toothed cats—to learn about their response to climate change. As it turns out, the toolkit she uses is just as effective when applied to humans.

“It was a lot of fun to take the tools that I normally use on extinct mammals and apply them to the humans from Huaca Prieta,” DeSantis says. “I’ve worked on giant ground sloths and saber-toothed cats and marsupial lions—some strange creatures—to understand their ecology and why they went extinct. But as soon as I started working on humans, it felt so personal.”

DeSantis’ approach involved drilling the teeth for stable isotope data, which revealed the ratios of certain elements, like nitrogen or carbon, that correspond to particular foods in an individual’s diet. She also performed dental microwear texture analysis, examining three-dimensional models of the abrasion marks left by the foods an individual ate.

Her findings from both methods confirmed what other evidence had suggested: that the diet of the inhabitants of Huaca Prieta gradually shifted from being exclusively maritime to being more reliant on crops, eventually leading to two coexisting economies on the coast, as is the case today in Peru.

“It was exciting to see how the two lines of evidence converged on the same interpretation,” she says. “Both converged on the fact that it was mostly a marine-dominated diet at first. Then you could see a shift in the carbon values being picked up, showing more corn entering the diet as time went on.”

IMAGES ABOVE COURTESY OF TOM DILLEHAY

ABANDONMENT

In the end there was no dramatic upheaval, no natural disaster or violent conflict, to mark the end of Huaca Prieta. The mound simply fell into disuse as the economy changed and its ceremonial significance diminished, although it was subsequently used as a burial ground up to late colonial times in the 18th century.

“Two things were going on: People were turning more toward agriculture inland, drawing off the water from the river using canals, and they were moving away from the coastline,” says Dillehay, referring to the advantages afforded by the silty flood plain that was newly formed by the El Niño floods. “Eventually, it was just abandoned as a ceremonial center.”

Other mounds—Paredones and El Brujo—had risen in the valley by then and supplanted Huaca Prieta in importance. And yet the Black Pyramid remained, preserved by the dry desert air, bearing silent witness to the passage of time.

The descendants of those ancient builders might have turned their backs on the old ways and forgotten what had first beckoned their ancestors to that spot thousands of years before, but one would like to think that Huaca Prieta continued casting its spell over the valley. One can imagine their looking in its direction on a clear night with the Milky Way ablaze above it. And perhaps if they squinted just so, the stars cresting its shadowy bulk would resemble a trail of sparks, just like the ones from the fires that had burned brightly on its slopes so long ago.

Monuments Man

The government of Chile, in conjunction with UNESCO, has announced plans to build a museum in the southern city of Puerto Montt featuring the discoveries of Vanderbilt archaeologist Tom Dillehay. Dillehay’s excavations of a nearby site called Monte Verde revolutionized understanding of how and when the Americas were first peopled. Puerto Montt is a tourist hub for cruise ships that draws about 800,000 visitors from around the world every year. The museum is scheduled to open sometime in 2018.

Dillehay, the Rebecca Webb Wilson University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, Religion and Culture, has worked in Chile for nearly 40 years, is a dual citizen of that nation, and holds several academic appointments at Chilean universities. “This is a great honor,” he says. “I greatly appreciate this rare opportunity to bring these discoveries directly to the people of Chile and visitors from all over the world.”

Until the 1970s the prevailing understanding was that the Americas first began to be populated 13,000 years ago by big-game hunters from Asia who used a distinctive type of fluted stone projectile point called a Clovis point. Dillehay’s work revealed the remains of a settlement belonging to a technologically and economically distinct human population that predated the Clovis people by more than a millennium. Subsequent excavations by Dillehay have pushed that timeline back even further, showing that cold-adapted people were well established in the area more than 15,000 years ago—during the final centuries of the last ice age.

The age of the settlement is not the only remarkable thing about it, however. “It’s the only Pleistocene Ice Age settlement in the world where you find such excellent preservation of organic materials,” Dillehay says. “At most archaeological sites you get stones, maybe bones if you’re lucky, but here we get the full spectrum: soft tissue, meat, hides, knotting, architectural remains of long tents and structures, some genetic evidence now coming out of the humans who were there, and a lot of wood and other items. It’s just an amazing record.”

Because of its archaeological significance, UNESCO is currently considering an application to have Monte Verde named a World Heritage Site.

The Museo Monte Verde also will feature exhibits interpreting Dillehay’s ethnographic research of Chile’s native Mapuche people. Dillehay is the project director on the political identity of the Mapuche’s ancestors, the Araucanians, who resisted the Spanish Empire, and the impact of that resistance on their descendants. The facility also will serve as a research station for scholars working in the region.

Dillehay will spend the fall semester in Puerto Montt to work on the museum’s exhibits, and will lead a Vanderbilt Travel tour to Chile, including Monte Verde, in November.

—LIZ ENTMAN