In the bustling labs of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Basic Sciences, Professor Richard Sando’s enthusiasm for neuroscience is palpable. His eyes light up as he discusses the intricacies of synapses and neural circuits. It is hard to imagine that this same man once received a D-minus in his high school AP Biology class.

“It was very uninspiring the way it was taught,” said Sando, an assistant professor of pharmacology and faculty affiliate of the Vanderbilt Brain Institute. That early setback, however, did nothing to dampen his passion for science. In fact, it is a testament to the unpredictable nature of scientific discovery—a theme that has defined Sando’s career and recently earned him one of the most prestigious recognitions in his field.

In 2024 the National Institutes of Health awarded Sando a New Innovator Award, part of their High-Risk, High-Reward Research program. This award, which provides $1,500,000 over five years, supports early-career scientists proposing innovative and impactful research that might not get funded in the traditional peer-review process due to its inherent risk.

“Professor Sando’s journey is a remarkable testament to the power of perseverance and the profound impact of curiosity,” Provost C. Cybele Raver said. “His achievements remind us that setbacks can be the stepping stones to breakthrough moments. At Vanderbilt, we are incredibly proud to support his innovative research as he continues to push the boundaries of our understanding of the brain, paving the way for discoveries that will benefit science and society alike.”

From lab volunteer to neuroscience pioneer

For Sando, a first-generation college student from a blue-collar family, the path to this honor was born of inspiration. His journey began during the summer after his sophomore year at Rider University when he volunteered in a lab. “I completely fell in love with the whole process,” he said. “It’s the mythology, the discovery, the trial and error—I love it! Everything about it was fun to me, and I knew then what I wanted to do.”

Sando loved the lab, and he worked in a special one, studying with Phil Lowrey, BS’91, known for his work on the molecular mechanisms of the circadian clock (and who earned his B.S. in biology from Vanderbilt). Sando changed his major from pre-med to pursue a Ph.D. in molecular biology.

After completing his Ph.D. at Scripps Research Institute under the mentorship of Anton Maximov, Sando’s scientific journey led him to Stanford University for his postdoctoral work. At Stanford, Sando “fell in love” again, this time with the synapse, when he collaborated with Tom Südhof, professor of molecular and cellular physiology at the Stanford School of Medicine. Sando was part of the team when Südhof’s work on synaptic transmission won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2013.

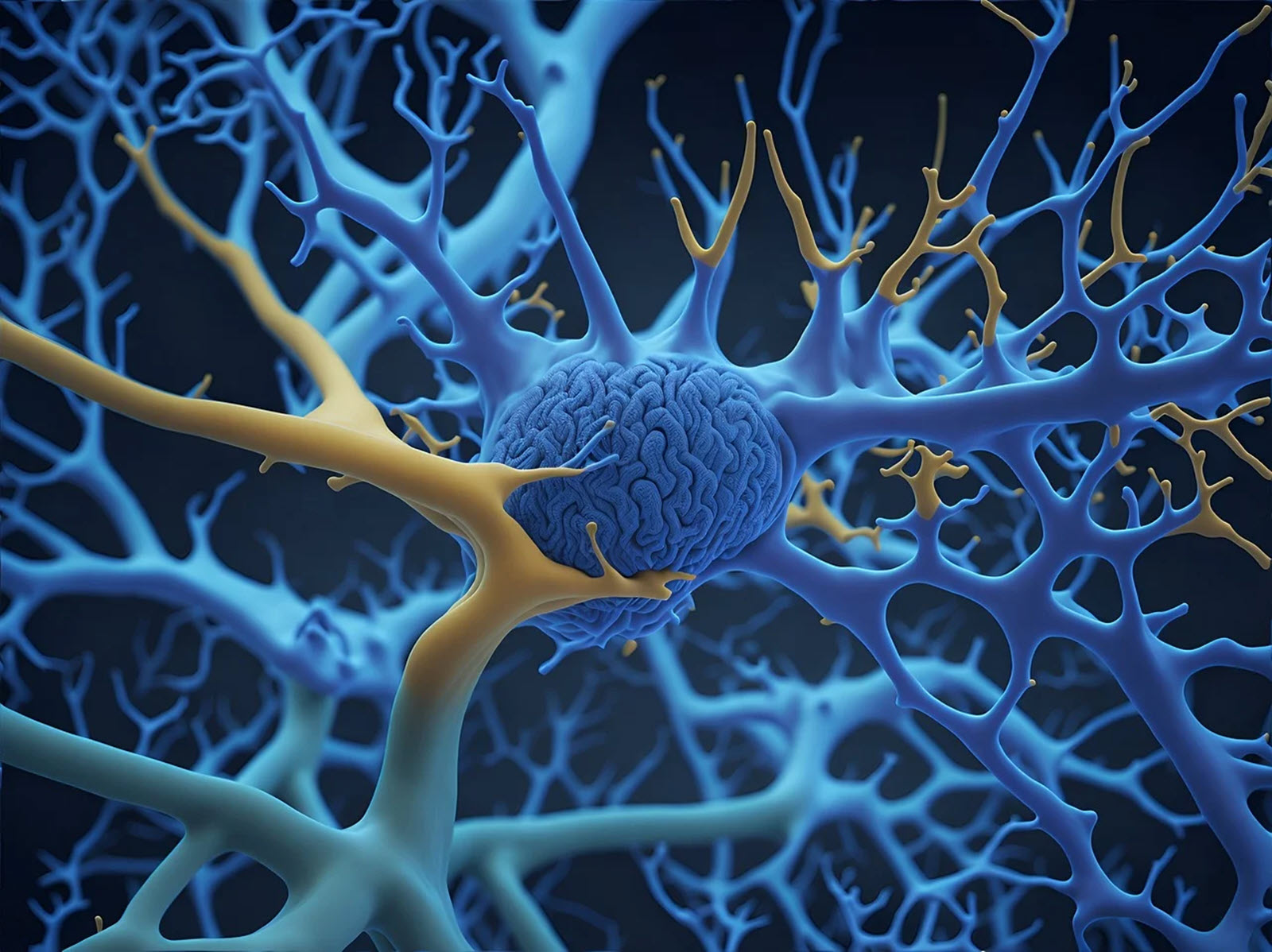

In the midst of the pandemic, in 2020, Sando set up his lab at Vanderbilt University. Their work is focused on understanding how circuits in the brain are assembled at the most fundamental level. “The human brain is composed of billions of diverse cell types that form networks of trillions of synaptic connections,” Sando said. “We want to understand how this synaptic connectivity becomes established during development.”

This research question forms the core of Sando’s NIH-funded project. He aims to unravel the cellular and molecular principles behind the brain’s remarkable ability to wire itself with incredible precision. “To really understand the brain at its most fundamental level, we need to learn more about how this happens,” Sando said.

Sando’s approach challenges the prevailing idea that molecular codes in the extracellular space alone can explain synapse formation. He believes that there must be intracellular signaling pathways corresponding to these molecular codes, directing the formation of diverse types of synapses.

“We are very proud of the major advances in neuroscience coming out of Richard Sando’s laboratory concerning synaptic circuits in the brain,” said John Kuriyan, dean of the School of Medicine Basic Sciences. “The New Innovator Award from the NIH is a significant recognition, and one that will help propel his laboratory to new heights.”

Sando is grounded in nature and soaring in science

“I was obviously thrilled,” Sando said of receiving an NIH New Innovator Award. “As a scientist, we deal with failure all the time. I submit tons of grants, and most of them get rejected. So, when I got the score for this one, which was a perfect score actually, it was even more shocking. It’s definitely an honor to be recognized.”

The significance of this award extends beyond mere recognition. It provides Sando with the resources and freedom to pursue his groundbreaking ideas. As Tara A. Schwetz, NIH deputy director, puts it, “The HRHR program champions exceptionally bold and innovative science that pushes the boundaries of biomedical and behavioral research.”

Despite his professional success, it is important to Sando that he remain grounded, drawing inspiration from nature and his family. The day before the award announcement, he was camping with his two sons, 6 and 8 years old. “Getting out in nature reminds me that there’s so much going on in biology,” he said. “We’re hyperfocused on synapses, but there’s a whole world of biology out there.”

At home, Sando finds joy in the sound of his 8-year-old learning to play the violin. If he were not a scientist, he muses, he would love to be a musician. This blend of scientific curiosity and appreciation for the arts seems to fuel Sando’s creative approach to research.

As he embarks on this new chapter of his career, backed by the prestigious NIH award, Sando remains committed to unraveling the mysteries of the brain. His journey from a struggling high school biology student to a pioneering neuroscientist is an inspiration to scientists everywhere.

In the end, Sando’s story is not just about scientific achievement. It’s a testament to the power of passion, perseverance and the transformative nature of scientific inquiry. As he continues to push the boundaries of our understanding of the brain, one thing is clear: The scientific community will be watching with great anticipation to see what discoveries emerge from his lab in the years to come.