When you think of sabertooth cats, chances are you picture the iconic Smilodon fatalis, which has massively elongated canines and is best known from specimens found in the La Brea Tar Pits in Southern California. (Smilodon fatalis fossils were also found in Nashville, Tennessee—which led to the name and mascot of the NHL’s Nashville Predators hockey team.)

However, the cat that once occupied all continents except Australia and Antarctica is the scimitar-toothed Homotherium. This cat’s teeth were more flattened and less elongated, but it was still a formidable predator.

According to a new study led by paleontologist and Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Larisa DeSantis and published in the journal Current Biology on April 15, Homotherium had a unique ecology that included the consumption of prey that resided in open grasslands. Among the prey were baby mammoths.

“Clarifying predator-prey relationships in the ancient past can provide insight regarding . . . conservation and management of apex predators living today—including lions, tigers and polar bears,” DeSantis said.

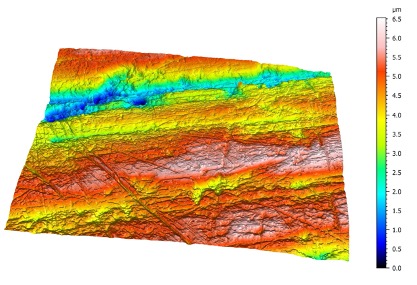

One of the most remarkable Ice Age fossil sites in the world is Friesenhahn Cave, a site outside San Antonio. Along with an abundance of Homotherium specimens, numerous prey species there (including a multitude of juvenile mammoths) led to the formation of the “Homotherium den” hypothesis—that these cats brought their prey back to the cave to consume it. DeSantis’ team of researchers integrated data from stable isotopes, dental microwear texture analysis and morphology—the branch of biology that deals with the form of living organisms, and with relationships between their structures—to reconstruct the ecology and biology of Homotherium.

“Morphology can give us a first approximation of diet and behavior, and in the case of Homotherium it indicates that it was a unique predator. It was truly a cat like no other, though it did share similarities with cheetahs and hyenas,” DeSantis said.

“Features like their inferred partially retractable, small claws and gracile forelimbs indicate that Homotherium was moderately cursorial,” said Mauricio Antón, co-author of this study, world-renowned scientific illustrator and Homotherium expert, based at the Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid. “But unlike cheetahs, which exhibit short bursts of high speeds, Homotherium probably ran farther for longer, though likely not as fast as living cheetahs.”

Homotherium was also unlike the Smilodon fatalis in that it had a preference for more open-habitat prey, based on the specimens in the cave (including a large number of approximately 2-year-old baby mammoths) and data from the teeth of Homotherium.

“As the saying goes, you are what you eat. In the case of fossils, we can examine the chemical makeup of their teeth and infer if they consumed prey that resided in grasslands or forests or both,” DeSantis said. “In our study, the stable carbon isotope data of tooth enamel from Homotherium were indistinguishable from that obtained from baby mammoths, while also consistent with the consumption of other primarily open-habit prey like bison and horses.”

In addition to studying the chemical signatures in their teeth, the researchers also studied the microscopic wear patterns formed during chewing. This study revealed that Homotherium not only avoided bone, much like modern cheetahs do today, but also ate tougher food than any living cat studied—consistent with the consumption of the tough flesh of baby mammoths.

“Our study essentially confirmed that Homotherium was an open-habitat predator that dined on baby mammoths,” DeSantis said. “While it is likely that Homotherium also ate some forest-dwelling prey, it is also clear that Homotherium had a clear preference for open-habitat prey.”

“This is the first study that shows Homotherium ate mammoths. It is a unique finding and presents breakthroughs in our knowledge of Homotherium,” said Julie Meachen, associate professor of anatomy in Medicine and Health Sciences at Des Moines University, who was not involved in this study.

“It is hard to study carnivores when carnivores are inherently rare in the fossil record,” DeSantis said. “Sometimes we can study carnivores from tar seeps, like at the La Brea Tar Pits. Other times we just get lucky and can study apex predators from amazing cave localities like Friesenhahn Cave.”

“Friesenhahn Cave is a jewel of a fossil locality,” said Ernest Lundelius Jr., professor emeritus at the University of Texas–Austin and co-author who published on the site in the early 1960s. “In addition to the big beasts like Homotherium, we can learn a lot from the other co-occurring animals in the cave.”

The research was made possible by the National Science Foundation and supported by Vanderbilt University.