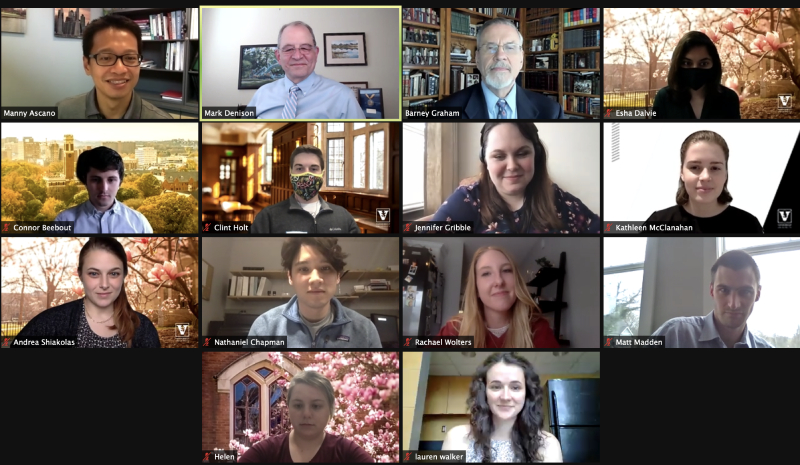

Vanderbilt’s role in shaping each step of the medical response to the pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 began three decades ago and is grounded in the determination of a small group of scientists to understand coronaviruses. The research, and the faculty and alumni who helped lead it, was the topic of the March 23 Vanderbilt Chancellor’s Lecture Series virtual event, “Vanderbilt in the Vanguard: The Decades-Long Journey to a Coronavirus Vaccine.”

The conversation outlined the path to the development of therapeutics for COVID-19 and what is expected to come next. The three panelists—Dr. Mark R. Denison, Dr. Barney S. Graham and Dr. Kathleen Neuzil—emphasized the importance of collaborative thinking and of scientific research with long-term horizons in solving the world’s greatest modern challenge. Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Susan R. Wente, a distinguished biomedical scientist and professor of cell and developmental biology who holds a Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair, moderated the event, which was hosted by Chancellor Daniel Diermeier.

Denison is the Edward Claiborne Stahlman Professor of Pediatrics, professor of pathology, microbiology and immunology, and director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Graham is the deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, NIH; and chief, Viral Pathogenesis Laboratory. Neuzil is the Myron M. Levine Professor in Vaccinology, professor of medicine and pediatrics, and director of the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Now spread out across the U.S., Denison, Graham and Neuzil once lived in the same Nashville neighborhood. They have never seen so much of each other as they have in the past year, however, as they have regularly joined infectious disease experts at the virtual table to share data, strategies and ideas to tackle the global pandemic.

To Denison, Graham and Neuzil, the most important lessons for the next pandemic center on investment in scientific discovery and creating pathways that reward collaboration. Graham called for a 194-country accord, similar to the Paris Agreement on climate change, focused on how to effectively manage emerging infectious diseases that know no borders. He also noted that there are 250 global vaccine groups working to develop a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2—a single virus. Instead, Graham thinks, groups should consolidate and tackle each of the 26 virus families that can infect humans and keep experts like him awake at night. “We need to harness our capabilities to more of a global approach to this problem,” he said.

COVID-19 therapeutics, including the Moderna vaccine and the antiviral remdesivir, were developed by the panelists, who shed light on the choices that were made. “The reason we chose [mRNA for this project] is because it is fast,” Graham said. “We wanted to pair our precision antigen design, or the atomic-level structure-guided antigens that we thought were the right thing for the immune system to see, with something that could have rapid delivery.”

The group confirmed that the successful development, substantial clinical trials and subsequent distribution of multiple mRNA vaccines will have a strong ripple effect on how other virus vaccines are developed, including those for emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Recent FDA guidance now clarifies that less grandiose clinical trials would be required for variant strains, with a process similar to those conducted for influenza strain changes.

“It is absolutely appropriate while we continue to improve and move forward with these highly effective [SARS-CoV-2] vaccines, that we do start to think about coronaviruses as a whole, as a family, and how we might target them,” Neuzil said of a pan-coronavirus vaccine. Denison shared his optimism that mRNA vaccines—which themselves are not viruses—will soon be used across many different viruses.

Looking back on the advances made throughout his career, Graham agreed. “The technologies we have [now] are so stunning—I couldn’t have imagined what we could do 30 years ago,” he said. “I think we have the tools to deal with these things. It’s a matter of investment.”

This investment is no more clearly understood anywhere than by this group, and by Denison in particular. Today he is recognized as a leading global expert in coronaviruses, but not long ago he struggled to continue research on a virus that no one knew or cared much about.

Funding research for non-obvious public health concerns may take decades to pay off, but all three researchers are hopeful that the past year has made the case for continued science and public-health-driven investments that don’t necessarily fit in an election cycle.

The work must be “predicated on a long-term biological understanding of the research,” Denison said. “I think of our work as being like an index mutual fund—it rises slowly, and not very many people find it interesting. But I think it’s better than a growth stock sometimes.”