Charles E. Roos, professor of physics, emeritus, at Vanderbilt University, who built his department’s research in areas ranging from superconducting wire to recycling technology, died on Feb. 20 in Nashville. He was 93.

Roos was born in Chicago on April 23, 1927. He enrolled at Swarthmore College when he was 15, later transferring to the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned a bachelor of arts in zoology. He also served in the Navy, where his training in electronics and radar technology changed his academic focus from medicine to physics.

Roos earned a doctorate in physics from Johns Hopkins University in 1953. His first job as a college instructor was at the University of California, Riverside, where his interest in high-energy physics drew him into experiments on the Cal Tech accelerator in Pasadena. In 1959, Roos was recruited to Vanderbilt, and he quickly established an experimental program in high-energy particle physics that received strong support from the National Science Foundation.

Roos became a key faculty negotiator during a tumultuous time on campus known as the Lawson affair. Many faculty members had threatened to resign after James Lawson, a Vanderbilt Divinity School student, was expelled for his leadership in the Nashville civil rights movement. A compromise was worked out that allowed Lawson to complete his degree, although he chose to transfer to Boston University. “It was not possible to build a major university with this problem,” Roos told Vanderbilt Magazine in 2002.

Among Roos’ research accomplishments, he led a team that designed and built a record-breaking 11 Tesla (unit of magnetic field) magnet. This prompted a team of metallurgists to descend on his lab from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory to make the first measurements on a new superconducting wire. Roos and a former student formed Cryomagnetics Inc. to manufacture and market superconducting wire.

“Charlie was an insightful and clever scientist,” said John Wikswo, the Gordon A. Cain University Professor, A.B. Learned Professor of Living State Physics, professor of biomedical engineering and professor of molecular physiology and biophysics. They first met when Wikswo was a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University. “I still remember a remarkable photo he once showed me of liquid hydrogen being repelled by the extraordinarily strong magnetic field in the hyperon bubble chamber he built for high-energy physics experiments in Switzerland, and every time over the past 42 years that I’ve taken seeds to my bird feeder, I carry them in a small plastic pail left over from Charlie’s recycling sorter project. I will always appreciate Charlie’s breadth of interests and enthusiasm for science and life. I learned a lot from him, and he was the key person in launching my career at Vanderbilt.”

Roos’ other colleagues included Nelson Fuson, longtime chair of the Fisk University physics department, and they worked together to build collaborations between the two institutions.

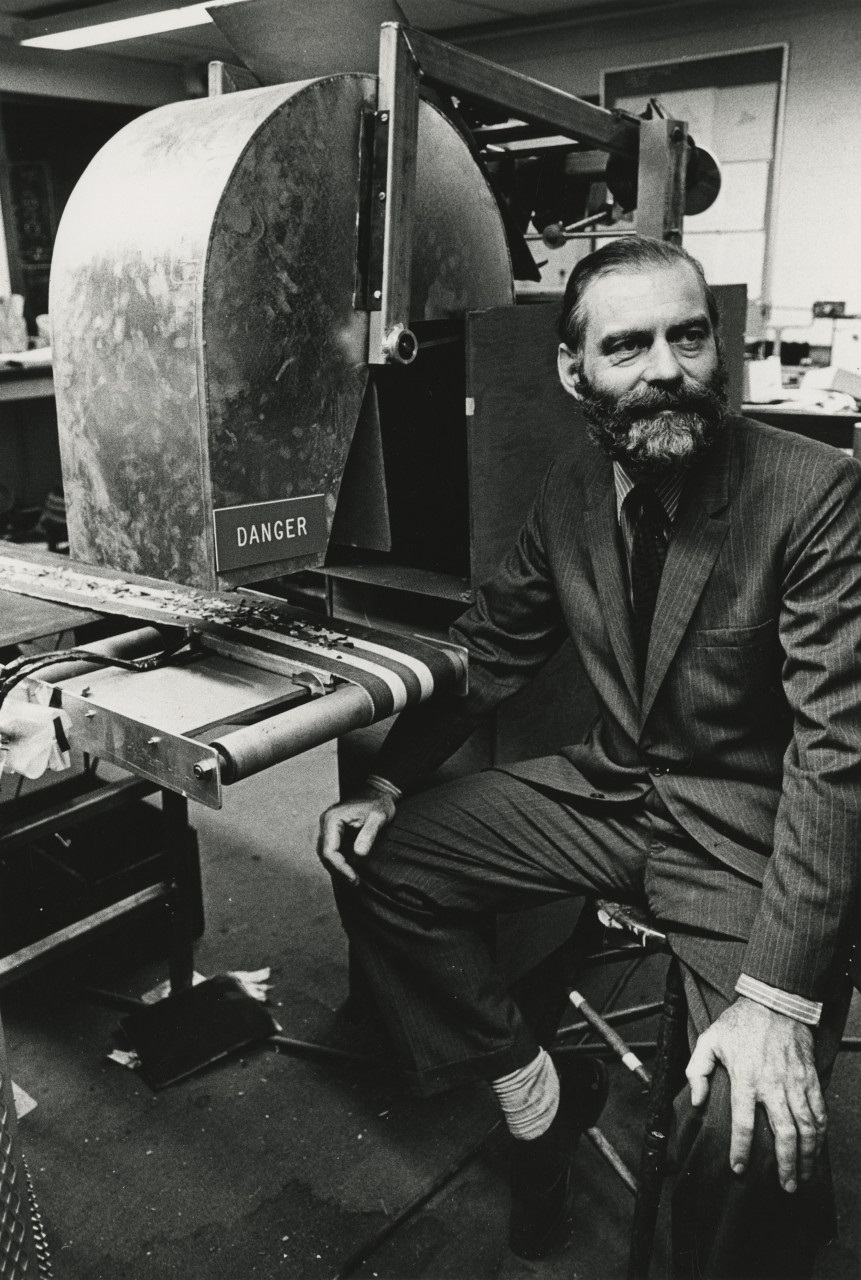

During the early 1970s, Roos led a Vanderbilt group that developed new technology for removing nonmagnetic, recyclable metals from other garbage. This research was supported by the Environmental Protection Agency and resulted in several U.S. and foreign patents.

Roos established National Recovery Technologies to do research and development and bring innovations to the marketplace. In 1989, he became an emeritus professor so he could focus on NRT, which diversified its sorting capabilities to glass and plastic. NRT technology made the automated sorting of recycled plastic possible. By 2010, NRT equipment sorted 70 percent of plastic bottles recycled worldwide. Roos led the company as chairman until 2013.

Roos was among those who testified in 1975 against construction of a planned nuclear power plant in Hartsville, Tennessee, on the banks of the Cumberland River, Nashville’s water supply. He used the newly emerging capabilities of computers to combine the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission’s own reports on all of the existing American nuclear plants and a classic nuclear power textbook to demonstrate that the economic justification for Hartsville was fatally flawed.

Roos is survived by his wife, Anne Roos, to whom he was married for nearly 69 years. He also leaves behind four children—Margit Roos-Collins, Alice Jensen, Carlton F. Roos and Charles D. Roos—and six grandchildren.

The family will plan a virtual celebration of his full life in the near future. If you would like to be notified, please contact a family member.