By Kim Green

The Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, with its roots in pioneering research related to disabilities, has long been a nexus for faculty, students and staff who translate that research into practice. In 1968 (having been founded three years earlier), the John F. Kennedy Center for Research on Education and Human Development officially opened, housing the Department of Special Education of George Peabody College for Teachers. That same year Eunice Kennedy Shriver, founder of Special Olympics, opened the first Summer Games in Chicago, a seemingly unrelated event that would become a global movement—and find a home within the Kennedy Center as well.

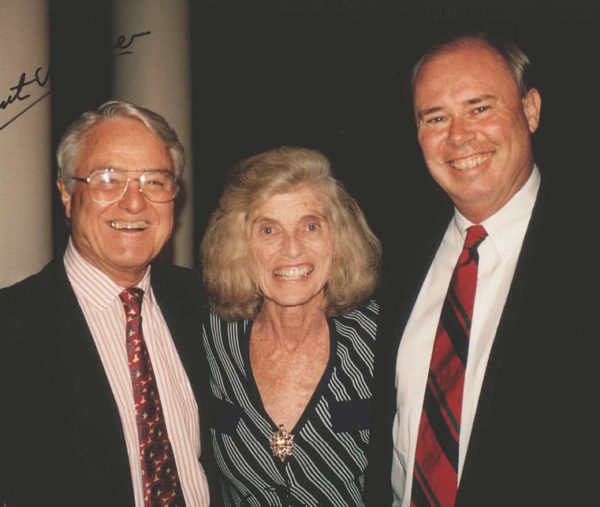

On a sunny July day at Soldier Field, a thousand young athletes from the U.S. and Canada watched as the Olympic flame was lit and Shriver recited an oath, attributed to the Roman gladiators: “Let me win. But if I cannot win, let me be brave in the attempt.” Shriver’s vision captured the imaginations of a group of like-minded folks at Peabody—among them, Jack G. Elder, EdS’73; Cecil Morgan, professor of health and physical education; and Neland Carver Hibbett, MA’60, EdS’75.

Elder, a teacher and coach from El Paso, Texas, had enrolled in a new graduate program at Peabody in 1972, at that time called Physical Education and Recreation for the Handicapped. He did fieldwork with Hibbett, then the recreational director at Clover Bottom Developmental Center, a Nashville institution for people with developmental disabilities. Hibbett had been working to offer Special Olympics programs at Clover Bottom and other state institutions, but the group had a broader vision.

“This might be where God wants to put me,” Elder remembers thinking, and he, along with Morgan and Hibbett, wrote a grant proposal to launch a statewide Special Olympics.

Winning that grant provided seed money for Tennessee Special Olympics, which was headquartered in the Kennedy Center at Peabody for nearly two decades. In 1973, Elder became the first salaried executive director and served in that post until 1988, when he became a regional director for Special Olympics International.

In the early years Tennessee Special Olympics focused on spring sports. Track and field, gymnastics and swimming events were held at local high schools, colleges and recreational centers. “We had great support,” says Elder, “but we had early challenges.” The main challenge was getting a new, ambitious project off the ground at a time when people with disabilities often were hidden away.

A big part of Elder’s job was outreach: fundraising, recruiting volunteers and area coordinators all over the state, and initiating training programs and competitions to qualify athletes for state events. To spread the word about their mission, Elder made speeches, wrote articles, met with media, and even knocked on doors, inviting his neighbors to watch the games. “When people saw what we were doing, they became believers,” he says.

Once Vanderbilt built its state-of-the-art track, the university became a mini Olympic village for the statewide spring games. Hundreds of athletes gathered there, stayed in the dorms and competed on campus.

“That was big,” says Elder, “for Special Olympics athletes to participate on the same fields where college athletes participate.” Elder recalls the festive feel of the event, with opening ceremonies echoing the pageantry of an ordinary Olympic games: the parade of athletes, lighting the torch, welcoming speeches and, always, the oath.

Cecilia Franklin, BS’81, MEd’83, who retired recently after working as a special educator for 37 years, says volunteering with Special Olympics athletes in Peabody’s Sunshine Saturday program helped cement her choice of life’s work. She recalls beautiful spring days, her fellow student–volunteers doling out hugs and cheers at the finish lines.

“We were in it together, figuring it out,” she says. “It opened my eyes and widened my world. It moved me ahead in my journey. It was a window into how much I would enjoy this work.”

Carolyn Russell was involved in the Tennessee Special Olympics for three decades—first as a volunteer, and later as a part-time staffer. For years she oversaw volunteers and noted how the experience changed people’s attitudes. She recalls how her own children were transformed by attending the events: “They became defenders of people with intellectual disabilities,” she says.

Under Elder the Tennessee Special Olympics program became recognized as one of the strongest and best managed. For athletes then and now, after five decades, Special Olympics is a chance to prove what they can do when given the opportunity.

Ron Bollinger directed Special Olympics training and competitions for 32 years, working closely with Elder for part of that time. “There are a lot of misconceptions about people with disabilities,” Bollinger says. “But once you meet an athlete, you realize everyone wants to live life to its fullest, to grow, and be accepted as part of society.”

“The desire to do their best is what any coach would look for in an athlete,” adds Elder, who was named Sportsman of the Year in 1984 by the Nashville Banner newspaper for his work. “You saw that on their faces. And you saw the joy of being able to participate.”

Kim Green is a Nashville freelance writer and public radio producer whose work has appeared in Fast Company, Parade, The New York Times, NPR and other outlets. She’s also a former flight instructor.