Two years ago, Fort Negley, a Union Army stronghold located a few miles east of Vanderbilt’s campus, was slated to be demolished to make way for one of Nashville’s newest mixed-use developments.

Yet, in part because of efforts by Vanderbilt researchers to document the vital contributions African Americans made to building and defending the site, not only was Fort Negley spared, but the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) also recognized it as a “Site of Memory” as part of its Slave Route Project at a ceremony May 21. The designation marks Fort Negley as a fundamental site to the public’s understanding of slavery, one of only four in the United States, joining the Statue of Liberty, Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, and the University of Virginia and Monticello in Charlottesville.

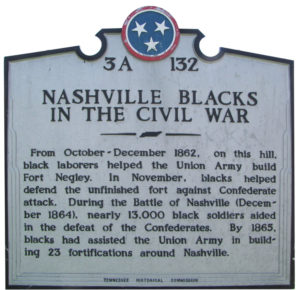

Built in 1862 by more than 2,700 runaway slaves and black laborers pressed into service by the Union Army, Fort Negley was the largest inland masonry fortification constructed during the Civil War. When Confederate forces attacked supply lines near Nashville, the African American conscripts were asked to defend the fort despite not being allowed to have weapons. Many of the descendants of these individuals later formed the historically black neighborhoods of Edgefield and Chestnut Hill, and also helped establish Fisk University.

Vanderbilt’s work on the site continues with the Fort Negley Descendants Project, a historical archive aiming to augment records about the fort, and to record the voices and stories of living descendants of the fort’s African American builders and defenders. Currently, the project is run by a team of Vanderbilt student and staff researchers, including postdoctoral fellow Angela Sutton, MA’09, PhD’14, who wrote the nomination for the site to receive the UNESCO designation.

“I got to pore over so much of Nashville’s history,” Sutton says of working on the nomination. “My favorite part was being able to talk to local people who know so much about the city.”

Vanderbilt senior Destiny Hanks also works with the group, helping write grant proposals and supplement research. She became involved with the Fort Negley Descendants Project after taking a class with Jane Landers, Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of History and current UNESCO representative for the Slave Route Project.

A similar class taught by Landers also sparked the interest of former student Eleanor Fleming, BA’00, MA’03, PhD’06. While she had remained casually interested in Fort Negley, Fleming—who went on to earn a D.D.S. at Meharry Medical College and now works in Washington, D.C., at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—grew personally interested after seeing some family names appear in a Twitter post from Fort Negley. It turns out that Fleming, a native of Franklin, Tennessee, is a descendant of two men who helped build the fort.

“This wasn’t part of our family history that we knew anything about,” says Fleming. “From that tweet, I got connected with the Fort Negley group and all the work they were doing to save the fort.”

Sutton says it was personal stories such as Fleming’s, combined with additional research about the fort’s history, that led to the UNESCO designation.

“This fort’s descendants have gone on to do amazing things with their lives, and they do it with so much purpose, knowing that their enslaved ancestors risked their health and lives on the hope that their descendants would have the freedom and equality that was denied to them,” Sutton said in remarks at the UNESCO ceremony in May. “For the descendant population, Fort Negley is sacred.”

Lila Johnson, a senior majoring in the communication of science and technology in the College of Arts and Science, compiled and edited this story.