By Michael Blanding

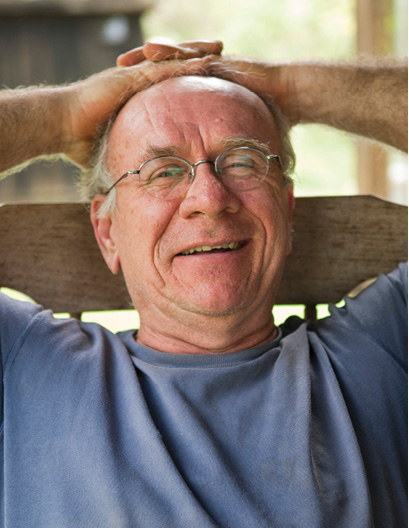

Bernie Ellis, BA’71, heard the helicopters before he saw them. Within minutes they converged, whirring, over his blueberry farm south of Nashville, as 10 federal agents drove up in four-wheelers. The moment he had always feared had arrived: He was being raided. The agents jumped out of their vehicles and started searching his house. The two lead agents, meanwhile, began interrogating him, demanding to know: Was he growing marijuana?

Ellis didn’t hesitate to tell them the truth. Yes, he was growing marijuana, he said, giving it to patients with late-stage HIV/AIDS and cancer in an effort to ease their pain and nausea. That day in 2002 was only the beginning of an ordeal that would consume him for the next 10 years. Ellis faced federal prosecution for marijuana cultivation and distribution, charges that carried a sentence of 10 to 40 years in prison, fines of up to $2 million, and possible confiscation of his farm. “It was completely nerve-wracking and emotionally debilitating,” Ellis says of the experience, which upended his career in public health.

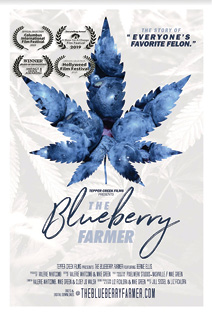

Now, as Ellis appears in a new documentary film about his story, The Blueberry Farmer, 33 states and the District of Columbia have approved marijuana for medical use. Of those, 10 states have legalized it for recreational use, some licensing businesses to sell pot in smokable and edible forms. Still, marijuana remains banned on the federal level as a Schedule I drug “with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” And in many states it remains banned. “In Tennessee,” says Ellis, “someone today growing for themselves and their terminally ill neighbors would face exactly the same risks I did 17 years ago.”

A SLOW TIDE

Ellis triple-majored in psychology, sociology and political science at Vanderbilt, combining all of those disciplines into a career in public health. In the 1980s he studied for a master’s degree at the University of California, Berkeley, where the AIDS crisis had hit the Bay Area hard.

“I met my first AIDS patient who was using cannabis for relief, primarily from the side effects of pretty toxic medication,” he says. When Ellis returned to Tennessee in 1987, he helped establish the state’s program for AIDS patients, and on the side, he began growing marijuana on his farm in Maury County, providing it to patients suffering from late-stage HIV or cancer. “Over a 15-year period, I probably helped 60 to 100 people,” he says.

Around that same time, the tide had begun to shift on marijuana, when California began allowing the drug for medicinal purposes. Other states slowly followed with their own statutes. Then when Barack Obama became president in 2008, he signaled a more tolerant approach to state reforms, allowing businesses to supply it commercially. In 2012 the floodgates started to open when Colorado and Washington legalized marijuana for recreational purposes as well.

“The argument began to shift from saying people need this drug medically, to an economic argument, that legalizing marijuana could generate jobs and tax revenue,” says Rob Mikos, a Vanderbilt law professor and one of the country’s leading experts on federal drug policy. “It creates all kinds of legal questions. Can states legalize something the federal government forbids?”

It’s clear, Mikos says, that the federal government has the authority to ban the possession, cultivation and distribution of marijuana under the commerce clause of the constitution. But that doesn’t mean it has the power to enforce that ban. The federal Drug Enforcement Agency has some 5,000 agents to enforce the laws for all drugs. That means it must rely on state and local officers for assistance. “The real constraint on federal power is a lack of resources,” Mikos says.

Notwithstanding the limits on its enforcement capacity, the federal ban is not entirely toothless, as Ellis’ case shows. Ellis says even though the local sheriff was aware of his operation, he looked the other way because he knew Ellis was providing it at no cost to the terminally ill. It was only when someone tipped off federal authorities that he was raided. After agents seized the marijuana plants from his farm, Ellis remained in a state of uncertainty for two years. “Day after day, you really have no idea what the future holds,” he says. During that time hundreds of patients, doctors and friends wrote letters to the judge, who eventually showed leniency in his case, giving him what amounted to a two-year probation without a fine.

If Ellis had his way, marijuana wouldn’t be illegal at all. “Saint Augustine said centuries ago that an unjust law is no law at all,” he says. “I think that applies completely to the 20 million people who have undergone an arrest related to cannabis.”

Ellis is not alone in his support of cannabis legalization. A recent Pew poll found 62 percent of Americans favor legalization, double the number from 20 years ago. Despite changes on the state level, however, Congress has been reluctant to change federal laws on marijuana, with proposed legislation to downgrade marijuana to a lower schedule, or de-schedule it entirely, routinely failing. The latest bill to remove marijuana from the Controlled Substances Act is expected to go nowhere.

That doesn’t mean that federal legalization is doomed, however. This year Congress quietly inserted a provision into the Farm Bill to legalize cultivation of hemp, a form of cannabis without the hallucinogenic cannabinoids, such as THC (tetrahydrocannabinol). And Mikos sees more promise in the STATES Act, a bipartisan bill introduced last year by Sens. Cory Gardner (R-Colo.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), which would essentially leave the question of legalization up to each individual state, and has a good chance of passing this year or next. “The trend is clearly in one direction,” Mikos says, “and that is toward legalization.”

NATURAL MEDICINE

That’s good news for Paul Kuhn, BA’65, a longtime activist with the nonprofit National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. Kuhn first heard about marijuana as a student on an ROTC scholarship at Vanderbilt, where he believed in the prevailing notion promoted by the government that smoking the substance would lead to an outbreak of lawlessness, crime and death. Later while serving in the Navy, he helped push for more severe penalties for marijuana use. When he entered business school at Indiana University, however, he was horrified to discover that more than half of his classmates smoked.

He began reading up on the drug at the library and found the dangers overblown. The next time it was offered, he tried it himself. “It was a fun, pleasant experience,” he says. “I remember thinking, ‘This is it? I have been lied to.’”

Soon Kuhn, who lived in Chicago at the time, became head of NORML’s Illinois chapter and began serving on the national board of directors. After moving back to Tennessee in the 1990s, he became an even bigger supporter of medical marijuana when his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer and relied on marijuana to counter the effects of nausea from chemotherapy. “It worked like a miracle, while the perfectly legal drugs failed,” says Kuhn, who rejoined NORML’s board after his wife died in 1996.

Opponents of marijuana claim that legalization increases crime and negatively impacts public health. The latest argument against the drug came in January with the release of the book Tell Your Children by former New York Times reporter Alex Berenson. The book highlights an association found in some studies between marijuana use and schizophrenia and other psychoses. Berenson also points to an increase in murders and aggravated assaults in four states that legalized recreational marijuana as evidence that marijuana leads to violence. Other opponents point to an increase in drivers with marijuana in their system involved in traffic accidents in Colorado. Kuhn takes issue with those arguments, saying THC can stay in a person’s system for weeks after ingesting marijuana, meaning they could test positive for the chemical even though they may not have been high while driving.

There also may be an association between marijuana and mental illness. Yet studies don’t show that marijuana is the cause of any mental illness—it may be that schizophrenics are using cannabis to self-medicate.

Dr. Sachin Patel, the James G. Blakemore Professor of Psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, agrees. While there is conclusive evidence that those who use cannabis are also more likely to later develop schizophrenia, he says the cause could work in the opposite direction.

“Maybe people have pre-existing symptoms before they get schizophrenia that might lead them to use marijuana more than someone without that liability,” he says. “If marijuana is really causing it, we should see an increase in the rates of schizophrenia in places where rates of cannabis use are clearly increasing.”

Patel has been studying cannabinoids for nearly 20 years. His research looks predominantly at natural cannabinoids produced in our brains, examining how they might help to reduce stress and anxiety. “Under most conditions,” he says, “the molecules the brain produces are trying to counteract the negative effects of stress.” He is currently engaged in studies of compounds that have been shown to boost cannabinoids in animals, hoping to eventually develop them for humans.

Last year Patel served as part of a group of 16 experts tasked with investigating the medical benefits and harm that marijuana causes. While the study didn’t prove all the claims of those who tout medical marijuana, neither did it support the criticisms of those who oppose it. In a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine for which Patel served as lead author, the researchers found “substantial” evidence that cannabis can reduce chronic pain and relieve symptoms of nausea.

On the negative side, the panel found it likely increases risk for social anxiety and with heavy use could increase suicidal thoughts. That somewhat paradoxical finding, says Patel, could be due to the way that chronic use of cannabis could change the cannabinoid receptors in the brain, overloading them and making them less susceptible to natural cannabinoids that reduce anxiety.

The panel’s biggest finding is that there is simply not enough evidence to make many conclusions about the health effects of cannabis either way. Because it is classified as a Schedule I drug with no therapeutic value, the government has made it difficult for researchers to legally obtain it for research.

WAVE OF THE FUTURE?

Even as medical marijuana has gained momentum around the country, one region that has held out on legalization is the South. In part, says Mikos, that’s due to the region’s conservatism. But it is also because many Southern states lack a referendum process for passing laws. “The public is more accepting on this issue, while legislatures are more conservative,” says Mikos.

Starting in 2005, Ellis began working toward creating medical marijuana legislation in Tennessee. The best chance came in 2014, when the legislature considered a bill called the Koozer–Kuhn Act, named in part after Kuhn’s wife. That bill was unique in that it included incentives for small farmers to raise cannabis, as opposed to larger conglomerates. Ultimately, however, it was defeated in committee.

A new bill was introduced before the Tennessee legislature in January, while states including South Carolina and Wyoming are also considering medical legalization, and a dozen states, including Connecticut, Minnesota, Texas and West Virginia, are considering full legalization.

For his part, Ellis is giving up on Tennessee, selling a portion of his farm and moving to New Mexico, where he plans to restart growing medical marijuana—legally this time. He hopes that the film, which is currently making the festival circuit, as well as being available on the streaming platform Vimeo, will help point out the injustice of marijuana prosecution.

“By illustrating the level of punishment that people are still at risk for, it might help accelerate the dialogue to re-establish cannabis programs everywhere,” he says. “We just need to retire this tragic and completely unnecessary war.”

A New Gold Rush

If cannabis is legalized on a national level, one of the people who has the most to gain is Smoke Wallin, MBA’93. Two years ago he sold out of his vodka and whiskey company, in search of a new venture. “My wife said, Before you do another drinks deal, you’ve got to look at cannabis—it’s the next big thing,” he says.

Last January, when California was set to legalize recreational marijuana, he joined with several partners to take multiple licenses and create a new brand, traveling to California to get started on the idea. “I literally haven’t left since,” he says.

Wallin is now president of Vertical, a company with more than 400 California licenses and a valuation of $285 million, one of the largest cannabis operations in the country. When the federal government legalized hemp last year, the company spun off a subsidiary, Vertical Wellness, with Wallin taking the helm as CEO. The company has locked up 2,000 acres of hemp in Kentucky that Wallin plans to use to produce cannabidiol (also known as CBD), a compound that has been used to treat symptoms of epilepsy.

The main challenge Wallin has faced so far is in raising money. Because cannabis is illegal on the federal level, most banks won’t touch the stuff; he’s had to rely on private investors for funds for the original company. Vertical Wellness, on the other hand, expects to raise $50 million for the hemp-based business this quarter, including participation from institutional investors. He expects to take the company public on NASDAQ late this year or early next.

Originally, Wallin planned to build up his business during the next five years as marijuana gained increasing acceptance, perhaps selling to a larger company then. Under current conditions, however, he is predicting passage of a national law within the next 18 months that could at least allow states to legalize cannabis. Now he is racing to scale up the company as quickly as possible, anticipating a coming bonanza of liquor, tobacco and pharmaceutical companies getting in on the action.

“We are decriminalizing a substance that a lot of people want,” he says. “The big drink and tobacco companies are all circling.”

Michael Blanding is an award-winning Boston-based journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, WIRED, Slate, The Nation, and The Boston Globe Magazine. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism at Brandeis University. His latest book, The Map Thief (2014, Gotham), was a New York Times bestseller and an NPR Book of the Year.