Most living things have a suite of genes dedicated to repairing their DNA, limiting the rate at which their genomes change through time. But scientists at Vanderbilt University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison have discovered an ancient lineage of budding yeasts that appears to have accumulated a remarkably high load of mutations due to the unprecedented loss of dozens of genes involved in repairing errors in DNA and cell division, previously thought to be essential.

In a study published May 21 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, Vanderbilt graduate student Jacob L. Steenwyk, working in the laboratory of Antonis Rokas, Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Biological Sciences, discovered that a group of budding yeasts in the genus Hanseniaspora, which is closely related to the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has lost large numbers of genes related to cell cycle and DNA repair processes. These losses are particularly surprising, not only because these genes are broadly conserved across living organisms, but also because mutations in the human versions of many of these genes dramatically increase the rates of different types of mutations and lead to cancer.

Steenwyk’s analyses show that the genomes of Hanseniaspora budding yeasts have lost hundreds of genes, including dozens involved in DNA repair, cell cycle, and metabolism.

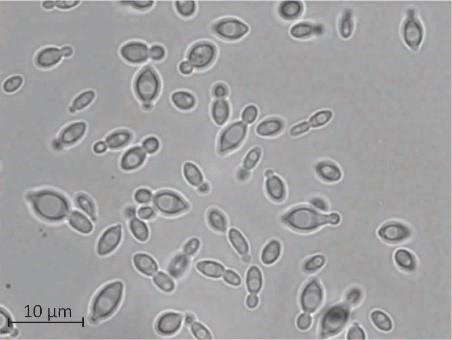

“It appears that, in genomic terms, Hanseniaspora are the yeast with the least,” said Steenwyk. “They have very small genomes and among the smallest numbers of genes of any species in the lineage. These dramatic losses of so many genes are reflected in the biology of these yeasts.”

A video comparing a Hanseniaspora species growing next to the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is available here.

“The speed with which the genomes of these yeasts have mutated is unprecedented, and their cell division appears to be extremely fast but also somewhat erratic — a quantity-over-quality approach, so to speak,” said Rokas. Due to the loss of these genes, Hanseniaspora yeasts have experienced many more changes in their DNA than their relatives and bear numerous “genomic scars” from natural mutagens from within and from the outside.

This work was partially funded by the National Science Foundation grants DEB-1442113, DEB-1442148 and DGE-1445197; Department of Energy Office of Science grants DE-FC02-07ER64494 and DE-SC0018409; Pew Charitable Trusts; and a Guggenheim Fellowship.