By Michael Blanding

After more than three decades in Tennessee state politics, Matt Kisber, BA’82, was ready for a change. His family had owned a chain of department stores when he was a kid, and from the time he was 6 years old, Kisber had worked his way up in the family business.

“It was a great life lesson,” he says. “It taught me a significant amount about responsibility, and how you interact with the public and treat your employees.”

His only regret was that he had never started a business himself. In 2010 he sought to correct that when he and his colleague Reagan Farr kicked around a number of ideas for an entrepreneurial venture. They eventually settled on a surprising contender: solar power.

“We kept coming back to this idea that solar energy was prevalent in Europe, and in the U.S. it was growing on the West Coast and would ultimately spread east,” Kisber says. “It could become a more widely accepted energy source as the price dropped.”

Their thinking went that companies and utilities wanted solar but did not want the hassle of constructing and operating it themselves. If Kisber and Farr could handle those tasks, they thought, they could tap into a market poised to explode.

They ran the numbers by outgoing Tennessee governor and serial entrepreneur Phil Bredesen, for whom Kisber worked as economic development chief. Bredesen was so impressed, he signed on as an adviser—and then a few months later, agreed to become chairman of their new company, Nashville-based Silicon Ranch Corp.

None of them had any idea, however, how successful they would be.

Eight years later the company, which employs several Vanderbilt alumni, develops, owns and operates solar energy plants across the U.S. It has built more than 2 million photovoltaic panels, producing 450 megawatts in 14 states—with another gigawatt of power in the pipeline. This past January, oil and gas giant Shell gave the company a major vote of confidence by investing $217 million to help expand Silicon Ranch’s business, demonstrating that even fossil fuel companies are now hedging their bets.

“It shows you how quickly this industry has evolved and is maturing into an everyday energy source,” Kisber says.

Solar power indeed appears ready for its moment in the sun after decades of unfulfilled promise, thanks to a combination of advancements in photovoltaic panel technology, rising fossil fuel prices, and a growing desire among the public to adopt renewable energy. And several Vanderbilt alumni, including Kisber, are leading the way to ensure that solar is not just a feel-good energy source but an economically viable one as well.

Powering Business

Kisber has long sought to make an impact on the world. He worked his way through a political science degree at Vanderbilt as a newspaper reporter covering Nashville politics. By his senior year, he decided he could do a better job than the politicians he was covering and threw his own hat into the ring, running for state representative out of his dorm room.

Surprisingly, Kisber won that race and served for 20 years in the state house before joining Bredesen’s administration, where his job as economic development chief included investments in solar and wind power. Even as he enjoyed creating policies, however, he longed to implement change more directly.

“In government you are setting policies, and someone else is going out and doing it,” he says. “Now we are doing it, and there is a great deal of personal satisfaction in that.”

Rather than competing with fossil fuels, Silicon Ranch partners with existing utilities to supplement the power grid with solar generation to help meet consumer demand. In addition, it provides energy directly to companies, nonprofits and government facilities. Among the most prominent of these is the solar farm for Volkswagen’s manufacturing and assembly plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Built in 2012, the 60-acre, 33,000-panel system generates 13.5 gigawatt hours annually, providing VW with enough clean, renewable energy to make its auto plant the first and only one in the world to be LEED Platinum certified by the U.S. Green Building Council.

When Kisber launched Silicon Ranch in 2011, the cost of producing a kilowatt hour of solar power was much higher than its fossil fuel equivalent. Since then, however, costs have dropped by two-thirds to make solar extremely competitive with fossil fuels. And unlike gas and oil prices, which fluctuate with global supply and demand, going up 3 to 5 percent a year, the consistency of the sun allows for stable pricing for decades. In fact, Kisber predicts in the long run his most recent projects will actually cost less than they would had natural gas been used.

Then there are the environmental benefits of solar. Silicon Ranch’s website includes a running tally of how many tons of greenhouse gas emissions the company’s panels have saved. At last count it was more than 429,000 tons.

“It is so exciting to come home from work every day and tell my kids what I did and how it’s making a positive difference,” he says. “We’re helping from an economic standpoint, an environmental standpoint, and I believe from a cultural standpoint as well.”

Global Access

While solar efforts like Kisber’s are helping to solve the problem of energy consumption in the U.S., citizens of developing countries face a starker problem—no access to energy at all.

“Around the world, 1.1 billion people live without energy access. One in seven people don’t have access to lights at night,” says Leslie Labruto, BE’11, who is taking skills she honed at the Clinton Foundation and putting them to use as global energy lead at Acumen, an organization using market solutions for social change.

Under Labruto’s leadership, the organization has strategically invested in companies installing home solar power systems in the remotest parts of Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Each system can charge a battery with enough strength to power three lights and a cellphone charger, dramatically improving a family’s quality of life.

“It’s low-cost, it’s decentralized, and it gives economically disadvantaged people an opportunity to afford energy that isn’t tied to fossil fuel consumption,” she says.

Labruto seemed destined to study engineering, growing up in a “women-centric” New Jersey home with her mom, grandmother and sisters. “We all did everything,” she says. “I was the one fixing the toilet and working on the sink.” Attending Vanderbilt with a scholarship, she was as excited to do hands-on projects as she was to travel the world.

“Vanderbilt was incredibly instrumental in helping me in my desire to be a global citizen,” she says.

Rather than a more traditional engineering project focused on city infrastructure, she conducted her senior project with an interdisciplinary team, helping design a solar- and bike-powered system to generate electricity for a school in Guatemala.

“It really opened my eyes to the fact that the world needs solutions and I can be a part of it,” Labruto says.

After graduation she served as a young alumni trustee on Vanderbilt’s Board of Trust and earned a master’s studying clean energy at Imperial College London. She then got a job at the Clinton Foundation working with small islands to transform their energy economies. She came to Acumen in February 2017, excited by its blend of social mission with venture capital.

“We’re purpose-driven first, but we’re also trying to make our money back to invest in more companies down the road,” she says. That frees companies to have access to flexible money, compared to grants that can have onerous conditions, and allows them to leverage Acumen’s seed investment to raise more money from investors and broaden their impact.

“Being an entrepreneur is tough,” she says. “We see ourselves as a partner to stand by your side while you’re trying to solve a business problem and do the right thing for the world.”

The same supportive self-reliance extends to customers of the solar home systems, which cost about $200 but are offered on a payment plan of, say, 20 or 50 cents a day. That makes it affordable even to those making just a few dollars a day, offering them an asset and a point of pride in the bargain. After establishing their credit-worthiness, customers can then work toward buying a larger asset such as a refrigerator or television, or even a solar-powered irrigation pump or milling machine.

“They don’t get a hand-out. They work toward something and can determine how to use it,” she says. “Things that really enhance quality of life but once seemed unobtainable are suddenly within reach.”

Technological Breakthrough

Even as Kisber and Labruto are spreading more solar power around the world, they are still limited by where they can install silicon photovoltaic panels, which are not always the most pleasing objects to look at. Enter Miles Barr, BE’06, who envisions a world in which solar power could really be all around us—even if we cannot see it. His company, Ubiquitous Energy, is pioneering a new technology to create a transparent coating that could be applied to virtually any surface to make it an instant solar panel.

“Imagine the glass face of a skyscraper being transformed into a giant photovoltaic energy generator,” Barr says.

Since the average building has more vertical than horizontal surface area, the technology offers a dramatic increase in the space that could be used for solar energy. But that is just the beginning of the applications Barr sees for the coating, which could be applied on homes, cars, or cellphones that could recharge their own batteries. The secret to the coating is organic dyes, similar to the kind one finds in blue jeans or house paint—only instead of capturing visible light, they absorb only the ultraviolet and infrared spectrums of the sun’s energy.

“There is energy in all of those parts of the spectrum,” Barr says, “but because they’re not visible to the eye, the coating looks transparent to us.”

Barr came to Vanderbilt to study chemical engineering and fell in love with the hands-on process of trying to create new organic molecules that could have a practical application in the real world. After earning his degree, he continued on to a doctoral program at MIT, where he joined a group trying to integrate solar cells into new materials such as fabric.

“But there was a glaring obstacle, which is how they look,” he says. “We felt there was an opportunity to more broadly deploy solar technology if you could seamlessly embed it into existing products and surfaces without changing their appearance.”

Since starting Ubiquitous Energy in 2011, Barr has raised $25 million and now employs 20 workers at his Redwood City headquarters in the heart of California’s Silicon Valley. So far the company has created small-scale prototypes of glass panels about a square-foot in size to demonstrate the concept. It also is currently partnering with glass and other manufacturing companies to incorporate the technology into their processes, in the hopes of producing new materials to supplement existing solar panels.

“You could have transparent solar on the glass and traditional solar panels on the roof, and they could all work toward enabling net-zero energy buildings,” Barr says.

This kind of many-shots-on-goal approach is crucial to the philosophy of Barr and his fellow solar pioneers. Whether it is fields full of photovoltaic panels, affordable solar homes in remote African villages, or cellphones that can charge themselves through innovative coatings, the number of approaches to harnessing and deploying the sun’s rays is growing. And they all point to a clean energy future that has never been brighter.

Michael Blanding is a Boston-based author and investigative journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Wired, Slate, The Nation, The Boston Globe Magazine and Boston Magazine. His latest book, The Map Thief (2014, Gotham Books), was named a New York Times best-seller and an NPR Book of the Year.

Totally Tubular

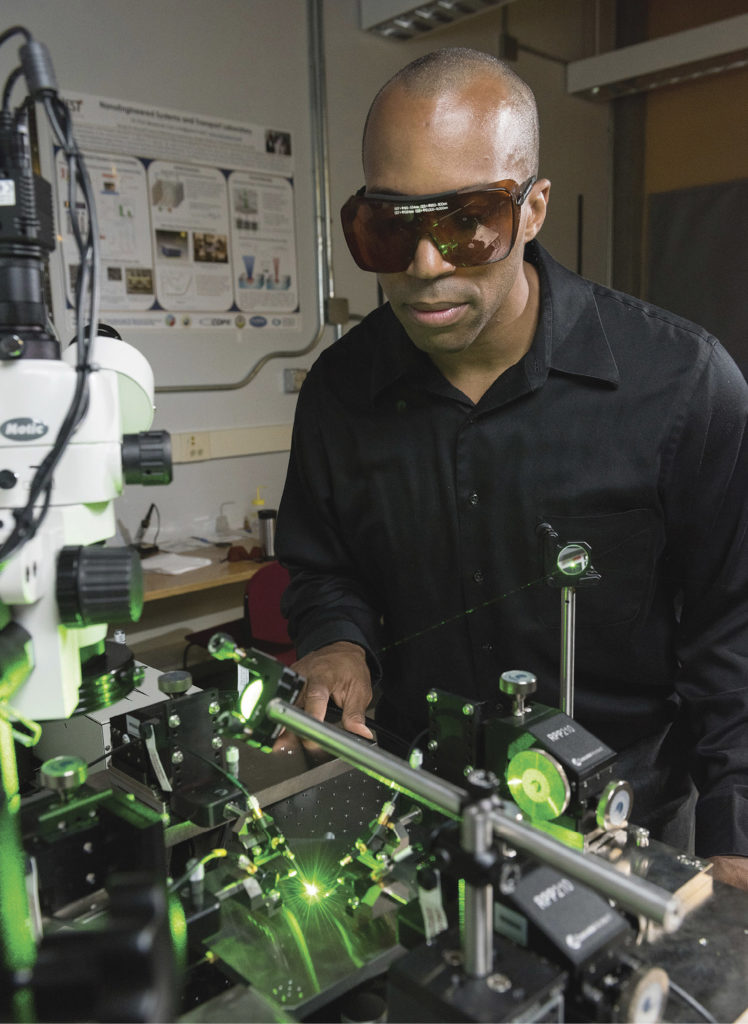

If not for a chance accident his first year at Vanderbilt, Baratunde Cola’s life might have turned out very differently. Cola, who goes by “Bara,” was a walk-on fullback for the football team, dreaming of one day going to the NFL, when he tore his ACL in a pickup basketball game.

“To be honest, I probably wasn’t going to come back to Vanderbilt the next year,” says Cola, BE’02, MS’04, but a coach convinced him to stay. “He suggested I come back on the equipment staff and work on the side to make some money for school.”

Cola, who was a mechanical engineering major, started doing paid research to make ends meet and discovered a love for lab work. (He also eventually made it back to football and won a scholarship.) After graduation he earned his master’s at Vanderbilt and his Ph.D. at Purdue University, where he studied carbon nanotubes—a wonder material 10 times stronger and 10 times lighter than steel.

That opportunity set him down a path to use the technology to transform solar energy production. Last year his efforts were rewarded with the prestigious Alan T. Waterman Award, a $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation recognizing outstanding researchers age 35 and younger.

“If you look at the course of human history, it’s really only every 100 years that there’s a new material that can transform how things are fundamentally done,” enthuses Cola, who is now an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech. “In the 20th century that was silicon, and a long, long time ago it was steel. It’s inevitable carbon nanotubes are going to be a dominant material like that.”

Today’s solar panels operate by absorbing the sunlight in the form of photons, which excite electrons that are then captured as electricity. The only problem is, more than 60 percent of the sun’s energy is lost as heat. If the sun’s energy could be absorbed in the form of waves, however, that heat loss could be avoided.

Cola set about to create a device called an optical rectenna, which in theory could use carbon nanotubes to turn electromagnetic waves directly into electricity—but no one had been able to build one so small that it could capture the frequency of visible light.

“It was the perfect kind of problem I would want to spend money and time on,” he says. “The chances are we wouldn’t be successful, but if we could, it would have a huge impact.”

For the next few years, Cola threw resources at the problem, working to construct an optical rectenna on the nanoscale. He hit pay dirt in 2015, publishing a paper demonstrating the first working version of the device. This year Cola’s team extended the basic demonstration to the first practical device that could be used in applications.

“Our recent work increased efficiency by a hundredfold,” he says. “It was a huge validation that we are on the right track.”

Last year Cola founded Carbice Corp. in Atlanta to continue developing carbon nanotube technology, raising $1.5 million in startup cash. He is currently figuring out how to manufacture his device in a way that it can be commercialized, experimenting with a flexible and cheap aluminum foil substrate to hold the tubes in place. If successful, it could dramatically transform the potential of solar power.

—Michael Blanding