A decade into his role as chancellor, Zeppos has no plans to slow Vanderbilt’s rapid progress—and he wants to bring the rest of higher education along for the ride.

By Ryan Underwood, BA’96

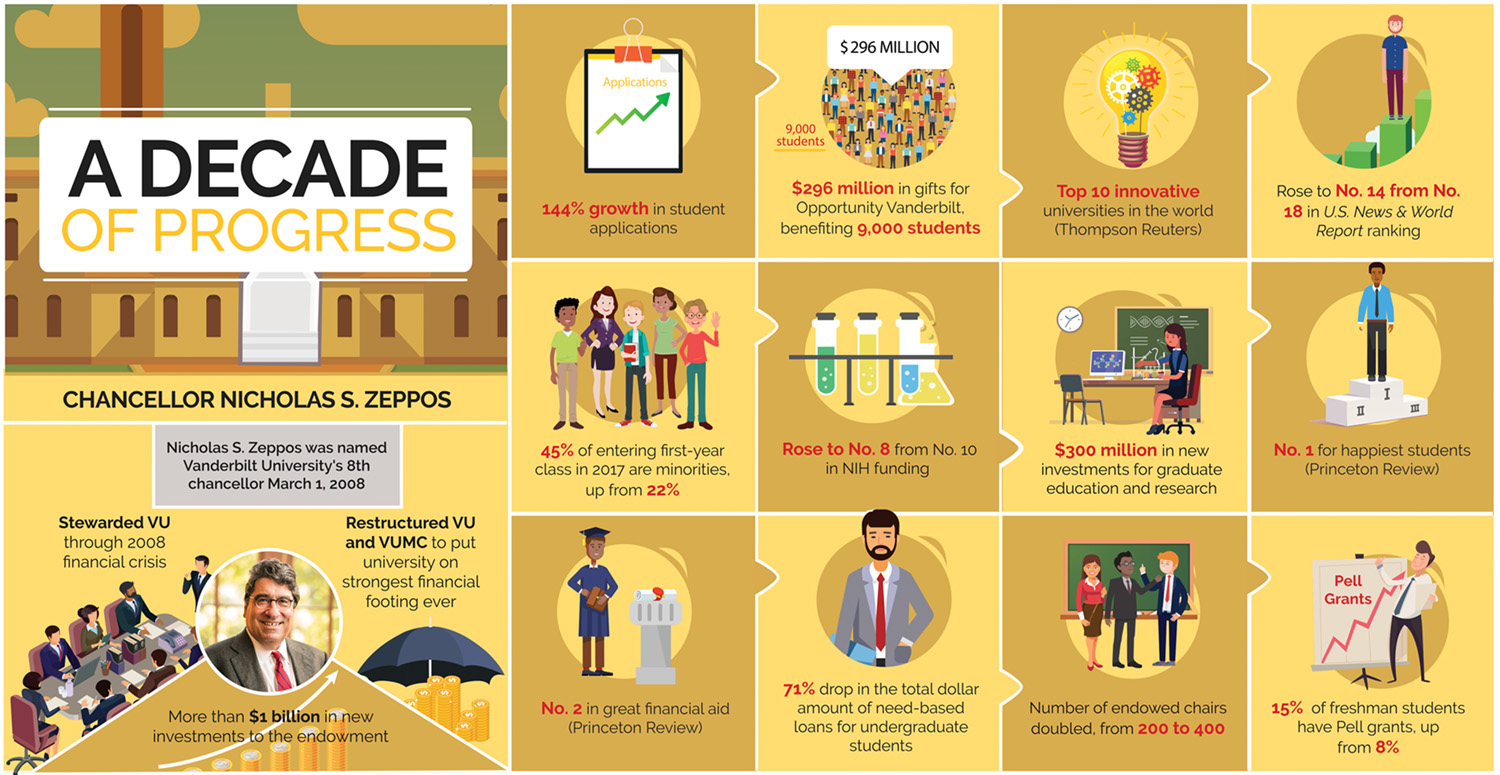

Sitting down recently to reflect on his 10-year anniversary as Vanderbilt’s chancellor, Nicholas S. Zeppos is quick to credit others, almost to a fault, when asked to describe various accomplishments.

Rankings are higher than they’ve ever been? That’s because the admissions and financial aid teams are so effective.

The successful split from Vanderbilt University Medical Center? The Vanderbilt Board of Trust and VUMC worked with the university’s finance office to make that happen.

Vanderbilt is attracting more faculty and researchers from top universities around the world? The provost’s office is doing a great job.

“I’m coach. I can’t play. I just put people in the game,” Zeppos says. “I always joke that, more than being chancellor, I’m really just a good HR person. I hire great people.”

Yet, there’s one area where Zeppos doesn’t hesitate to offer a full-throated boast: As a student, he always was at the top of his class. “I wasn’t a perfect kid,” Zeppos hedges. “But I was always a really good student.”

Perhaps that’s because he wasn’t interested in ice fishing or cross-country skiing and instead endured the long winters growing up in Milwaukee by reading whatever he could get his hands on. Or maybe he was inspired by his maternal grandfather, a hardworking but poorly educated Greek immigrant who brought his family to the U.S. seeking greater opportunities.

“There were six grandkids in my family, three boys and three girls. My grandfather always told us we were going to college and he would pay for it however he could,” Zeppos recalls. “I just took it for granted.”

Whatever it was, those early experiences helped shape a university leader who today is a passionate believer in the transformative power of higher education. Zeppos thrives in the day-to-day minutiae of running Vanderbilt, all in a relentless push to make the university better than it was a year ago, a month ago, or even just a week ago.

“Nick would like to build Vanderbilt’s reputation to a level where we’re second to none,” says Vanderbilt Board of Trust Chairman Bruce Evans, BE’81, a former managing director and now chairman of Summit Partners in Boston. “What drives Nick is a motivation to build and enhance Vanderbilt into much more than it was when he got here.”

It’s not (only) bragging rights that Zeppos is after. Rather, he truly believes that the more educational opportunities an institution can pack in—for students, for faculty, for the community—the more a university like Vanderbilt becomes an effective tool for making the world a better place. That’s something he’s experienced personally.

“Why do I have a good job? Not just as chancellor, but why did I have a good job as a lawyer? Why was I able to have high-quality health care or have my kids educated or own a home? It was all because of education,” Zeppos marvels. “Education is the ultimate vaccine. If you give people education, they usually have a job, health care, a place to live. They’re able to provide for their families. It’s not perfect, but it’s as good as you can get. That idea resonates with my own narrative: How is it that I could be a college professor—now chancellor—and my grandparents came to this country not speaking English?”

THE PATH TO KIRKLAND HALL

Zeppos officially assumed the title of Vanderbilt’s eighth chancellor on March 1, 2008, though his early path to the job was hardly preordained.

Starting out as a math major at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Zeppos eventually gravitated toward history, particularly legal history. He thought about pursuing a Ph.D. and becoming a history professor, but then turned his sights to law school. He continued at the University of Wisconsin, earning his J.D., magna cum laude, in 1979 and serving as editor-in-chief of the law review.

Zeppos began his legal career at the prestigious law firm Wilmer Cutler & Pickering (now WilmerHale) in Washington, D.C., and later joined the U.S. Department of Justice. “I liked practicing law. My cases were getting more complex and interesting—each one was like a law exam,” he says. “It was a lot of cutting-edge stuff.”

By 1986, however, he and his wife, Lydia Howarth, were expecting their first child and asked themselves if they really wanted to settle in Washington.

After a bit of soul searching, Zeppos says he returned to the idea of being a college professor and put himself on the academic job market. Vanderbilt Law School approached him, and by the time he returned from a campus visit, he was sold. “I remember telling Lydia that I’d never met so many smart people who were also really nice,” Zeppos says. Plus, Nashville offered an ideal blend of urban amenities coupled with the campus atmosphere one might find in a small college town.

Just before Christmas, Vanderbilt extended Zeppos an offer and he accepted right away. “No hesitation,” he says.

A specialist in administrative law, Zeppos quickly made his presence known on campus. His classroom style blended a lively humor with analytical rigor, earning him five teaching awards. Within a few years of arriving at Vanderbilt, he was tapped to serve as associate dean of the law school. It was during this time that his wide-ranging curiosity prompted him to look at what was happening across the rest of the institution.

Education is the ultimate vaccine. How is it that I could be a college professor—now chancellor—and my grandparents came to this country not speaking English?

“I was teaching law, and then all of a sudden I saw that there was this whole university committed to educating nurses and doctors and ministers and undergraduates—people who were going to go on to do fabulous things,” Zeppos says. “I saw that I could have a broader impact.”

By 1997, a decade after joining Vanderbilt as a junior faculty member, Zeppos decamped for Kirkland Hall to work for former provost Thomas Burish, who became an important mentor. “I wouldn’t be here as chancellor if it weren’t for Tom,” Zeppos says, noting Burish’s emphasis on using data to substantiate and drive important decisions. “I remember him talking about Vanderbilt having x-number of applications, yet these other schools have two-x. Why?”

Those discussions around boosting application volumes led Zeppos and others to conclude that a robust financial aid program held the key to widening Vanderbilt’s appeal to a degree that would encourage the best students from across the nation to apply. Opportunity Vanderbilt, the university’s nationally renowned financial aid program that was started in 2008 to replace student loans with no-obligation grants and scholarships, ultimately grew out of that early work.

Yet just because something makes sense on paper doesn’t always mean it will be embraced in the real world, especially when talking about a tradition-bound institution like Vanderbilt.

“It took a fair amount of courage and funding and leadership to say let’s do this. That decision to launch Opportunity Vanderbilt came over some resistance,” Zeppos says. “There are always people who like things just like they are. I fully understand that. If they went to Vanderbilt, or were already supporters, they already love the university just the way it is. It’s like, this is my house. Don’t paint it a different color. But the university has to change and get better, or it will die.”

By 2002, Zeppos was named provost and began focusing on the campus environment that new students—especially the ones attracted to Vanderbilt by its increasingly generous financial aid—would find once they got here.

Zeppos led efforts to add new academic offerings such as the popular Medicine, Health and Society program, as well as recruit and retain top faculty, a point he’s been “maniacal” about since his earliest days at Vanderbilt. “People ask me, ‘How do we become a top-10 school?’ One of the answers is by keeping your top-10 faculty from going to other schools!” he exclaims. “The faculty, the teachers, the researchers—they’re the continuous talent. They’re the ones students are coming to be with at Vanderbilt.”

The second masterstroke Zeppos developed came with residential colleges, a vast overhaul of the first-year living experience that would work hand-in-glove with Opportunity Vanderbilt. Students of different economic, cultural and racial backgrounds would be intentionally grouped together as roommates. Meanwhile, live-in faculty members would serve as both mentors and teachers in newly built houses that were designed to inspire Harry Potter-like allegiances.

The result was The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons, which opened on the Peabody area of campus in the fall of 2008, shortly after Zeppos rose from interim chancellor (or the “iChancellor” as he was called, in homage to Apple’s then-new smartphone) to the permanent role.

But the changes Zeppos has led are matched by his ability to make everyday connections with students. Aditya Karhade, BE’15, a young alumni leader on the Board of Trust, remembers his first impression of Zeppos as a faculty VUceptor, leading a Vanderbilt Visions group of first-year students. “Every week our group met at Kirkland Hall, and we learned about Vanderbilt alongside someone who had helped to shape so much of the university that we called home,” says Karhade, who is pursuing a joint MD/MBA degree at Harvard University. “He was one of the first people I met after I arrived on campus, and he remains one of my most important mentors after graduation from Vanderbilt.”

‘NEVER MISSED A BEAT’

Martha Ingram, the former chairman of the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, says when the university suddenly found itself without a chancellor in 2007, following the departure of Gordon Gee, Zeppos emerged as a “homegrown” leader who, by that point, knew Vanderbilt better than anyone.

“Of course, we conducted a national search. But we soon realized that our provost, Nick, stood head and shoulders above anyone else we were interviewing around the country,” Ingram says. “He’d already been quietly running much of the university. When the time came, it was a very natural progression for Nick to move into the foreground.”

Ingram, a longtime champion and benefactor of Vanderbilt, along with her late husband and former Board of Trust chairman, E. Bronson Ingram, says she’s enjoyed watching Zeppos grow ever more confident in his role as chancellor during the past decade. “Vanderbilt never missed a beat. It has continued on this upward trajectory under Nick’s leadership,” she says. “That doesn’t just happen. It takes a lot of work behind the scenes. But because Nick is such a consensus builder—and he approaches his job with so much warmth toward the people he’s working with—he has accomplished all of this with minimal conflict.”

Ingram points out that Zeppos is a tireless promoter of Vanderbilt, saying he’s “a salesman, in the best possible sense of the word.”

But that’s his public side.

Mark Dalton, JD’75, former chairman of the Board of Trust, notes that he sees much of the legal scholar in the way Zeppos approaches his job. “He knows how to research, to think analytically, to be reflective, and propose answers to issues and solutions to problems.” The result, Dalton says, is a leader who can connect vision to action.

You could see this as he committed to staying on course to launch Opportunity Vanderbilt (which is about halfway to its ultimate fundraising target, he points out) amid the darkest months of the 2008 financial crisis. You could see it in his expansion of the residential colleges, announcing an ambitious $600 million plan earlier this year to reshape West End by the time of Vanderbilt’s 150th anniversary in 2023. You could see it when he led the legal and financial separation of the university from VUMC, a daunting but necessary feat he didn’t want to see “kicked down the road.” And you continue to see it in programs around diversity and inclusion, mental wellbeing, and support for faculty research.

Dalton says he’s been particularly impressed by Zeppos’ support of trans-institutional programs. These initiatives have helped break down historic silos across campus, he says, and in turn, fostered a culture of collaboration and innovation that benefits students and faculty. “This is a key element of Vanderbilt, and truly the secret sauce that Nick Zeppos has developed in his 16 years as provost and chancellor.”

Susan R. Wente, provost and vice chancellor for academic affairs, says Zeppos sets priorities based on his “deep caring” for individuals in the Vanderbilt community. He then draws on his insatiable curiosity to dive deep into topics that he deems important to the university. “He’s been here for more than 30 years, going from an assistant professor to chancellor, and so he comes with a huge base of knowledge,” Wente says. “And yet, he’s always listening to others and wants to learn more.”

Evans, who has spent his career investing in companies and has worked with hundreds of CEOs, says Zeppos is one of the best managers he’s ever encountered. Anywhere. “A lot of people have a skill set that you could define as ‘big picture’ or ‘strategic.’ The other skill set people tend to have is more operational, more detail-oriented,” Evans says. “Chancellor Zeppos has both. That’s a rare combination.”

ROADMAP FOR SUCCESS

Like any good leader, Zeppos has spent years developing a comprehensive strategy, returning to that playbook continually as the university embarks on new programs and initiatives. Despite its nondescript name, the Academic Strategic Plan represents a finely tuned engine for driving Vanderbilt to new heights across a range of measures.

“Taken as a whole, the Academic Strategic Plan describes a thoughtful, multipart system designed to produce well-educated men and women,” says Evans, who has played an extensive role in shaping it and makes clear that it will continue to guide Vanderbilt’s priorities for the foreseeable future.

The first part of the plan revolves around Opportunity Vanderbilt’s mission to attract the very best students without regard to their financial means. The second part is to create a cohesive community out of those individual students. That involves not only expanding the living–learning concept to all undergraduates but also boosting the psychological and social resources on campus to match the pace at which the student body is changing.

“We were a strong university when I came to Vanderbilt. Today we’re more inclusive, more diverse, more academically rigorous, more selective, more innovative, more entrepreneurial, more global,” Zeppos says. “But I do think that one of our challenges—and I would say that we’re behind on this—is that the students have changed so quickly, we need to continue to pay attention to the psychological, social and inclusivity systems in place.”

The third part of the university’s strategy focuses on recruiting and retaining faculty talent, particularly by increasing the number of endowed faculty chairs. Since Zeppos became chancellor, the number of endowed faculty chairs has doubled to more than 400, and more are being added each year. In addition, the university has opened a new state-of-the-art Engineering and Science Building, which also houses Vanderbilt’s center for innovation, named the Wond’ry. Projects are underway to renovate Divinity School, School of Nursing and Peabody College facilities, as well as several core historic buildings on the central part of campus. The Owen Graduate School of Management is also exploring options for a new building.

The last part of this plan aims to foster innovation and collaboration across the disparate parts of campus. This can be seen in the implementation of the Trans-Institutional Programs (TIPs) faculty research grants, as well as a new immersion learning requirement for undergraduates in which they produce a capstone project based on real-world experiences such as internships or lab work.

“Now, we just have to go raise the funds to fully implement everything in this plan. That’s next on our list of goals,” says Evans, who announced in April that he and his wife, Bridgitt, had committed to a $20 million gift to the university. He notes that Zeppos also leads by example when it comes to philanthropy.

The chancellor and his wife, Lydia, have personally contributed to numerous university scholarships, fellowships and capital projects. “I truly believe that a mission-driven organization like ours requires giving of all kinds,” he says. “And, ideally, I’d like to see it come from everyone in the Vanderbilt community.”

THE NEXT CHAPTER

Beyond the individual components of the Academic Strategic Plan, there’s one overarching goal that Zeppos has become increasingly passionate about during the past year—a goal that reimagines not only Vanderbilt’s role as a university but the purpose of higher education as a whole. In short, he wants universities to reclaim their rightful place as a vital thread in the social fabric of the United States.

“America’s greatest institutions are its colleges and research universities. They are the foundation of our democracy, the linchpin of our economy,” Zeppos says. “I tell people that the American dream runs down two streets: Main Street and the point where it crosses University Avenue. We need to find that common ground of what it means to be an American, of what we can become as human beings. As a campus, we have no excuse for failing to say—every day—that we are going to change the world.”

It’s not just that universities have a role to play in improving society through research breakthroughs, or educating students who will go on to change the world in important ways. Vanderbilt and other universities can also help mend a divided culture by fostering a climate of civic engagement. “That doesn’t mean being a politician. It means being an active and productive member of a community,” he says. “E pluribus unum—out of many, one. That is the crux of the American experiment, and it is part of the important work we do at Vanderbilt and other universities.”

Zeppos increasingly talks about how higher education serves as a central element of civic engagement. He has begun to spread this message as vice chair of the Association of American Universities (AAU), a nonprofit organization of 62 leading public and private research universities whose missions include working in partnership with the U.S. government and advancing university research and higher education more broadly. Closer to home, Zeppos has convened a faculty committee to explore ways to raise the profile of universities and scholarship in the public sphere. Zeppos himself has grown more outspoken on issues that directly impact higher education, such as federal spending and immigration.

“Vanderbilt is a very distinguished, important institution—we need to be more active and vocal about the role we play in society,” he says. “If you count my time as interim, I’m going into my 12th year as chancellor. I’ve got some thoughts, and I’m ready to share them.”

Watch a video about Zeppos’ 10 years as chancellor: