While survival rates continue to rise for children with once-fatal health conditions like brain tumors, leukemia and congenital heart disease, that survival comes at a cost: long-term, and sometimes permanent, learning deficits.

The conditions themselves—along with life-saving medical interventions like surgery, chemotherapy and radiation—often take a significant toll on the region of the brain associated with learning, emotions, behavior and thought. Additionally, the chronic stress associated with having a serious health issue further disrupts brain activity, resulting in difficulties with memory, attention and executive function.

Psychology and Human Development’s Bruce Compas conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis to document the magnitude of this problem as part of his collaborative research on stress and coping, funded by the National Institutes of Health.

He is nationally recognized for his expertise on the effects of stress on children and families in crisis, including those living with cancer and depression, and the efficacy of coping skills to manage the impact stress has on the body.

“Millions of children survive their conditions … but are returning to the classroom with serious learning and behavior issues.”

—Bruce Compas, professor of psychology

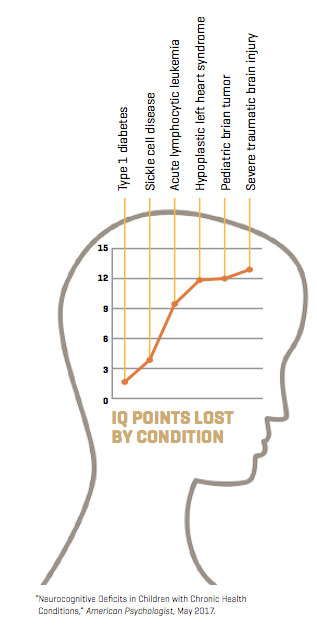

For the study, Compas and his colleagues examined neurocognitive outcomes for children with six common pediatric conditions: leukemia, brain tumors, sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease, Type 1 diabetes and traumatic brain injury.

Their findings, recently published in the American Psychologist, were sobering: About 4 million children were performing academically far below their peers and had lost multiple IQ points.

Hiding in plain sight

“What we have is a hidden epidemic,” says Compas, who holds a Patricia and Rodes Hart Chair at Peabody. “Our study confirms just how pervasive the problem is. Millions of children survive their conditions, thanks to improvements in medical interventions, but are returning to the classroom with serious learning and behavior issues.”

“What we have is a hidden epidemic. Our study confirms just how pervasive the problem is.”

—Bruce Compas, professor of psychology

Of the six conditions examined, patients who survived pediatric brain tumors and traumatic brain injury took the hardest hit on neurocognition resulting from the disease or the injury itself, as well as surgeries and other interventions. On average, these children were performing academically below 70 to 80 percent of their peers and had experienced a loss of 9 to 13 IQ points.

Children with diseases of the blood and heart also suffered significant brain function deficits. Acute lymphocytic leukemia, for example, is a fast-growing and invasive cancer that disrupts the production of normal blood cells, limiting the delivery of oxygen to the brain. In addition to the damage the disease causes, the patient typically must undergo chemotherapy delivered directly into the cerebral spinal fluid, which is known to damage brain cells.

Compas found that children with a specific form of congenital heart disease, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, as well as the hereditary condition sickle cell disease also suffered serious neurocognitive side effects.

Sickle cell disease causes disrupted flow of oxygen-rich blood to the brain, and children with sickle cell can have frequent mini strokes.

Children in both groups were found to perform academically below more than half their peers.

“These six conditions seem very different on the outset, but the impact on learning can be significant, and last a lifetime,” says Compas, professor of psychology and human development and professor of pediatrics. “On top of that, chronic illness causes a great deal of stress for the child and for the whole family. Being in a state of chronic stress causes neurons to shut down and the brain goes into the state of ‘fight or flight.’”

Compas and his colleagues found that children living with Type 1 diabetes suffered the fewest cognitive side effects, but there were still detectable deficits.

These patients showed decreased spatial ability, motor speed and focus, and scored below their peers on reading and writing tests. Type 1 diabetes is pervasive, with more than 15,000 children diagnosed each year, according to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

“One of the most surprising aspects for me … is how little cross talk there has been across disciplines.”

—Sarah Jaser, assistant professor of pediatrics

Study co-author Sarah Jaser, MS’03, PhD’06, previously worked with Compas as a graduate student in his Stress and Coping Research Lab and currently serves as assistant professor of pediatrics in the Ian M. Burr Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“One of the most surprising aspects for me about this particular study is how little cross talk there has been across disciplines,” Jaser says. “The standards for care differ quite a bit by chronic health condition, even though the learning deficits are similar.

“My goal is to promote the best possible outcomes in children with diabetes and their families, and it’s a huge benefit to be able to continue to collaborate with Bruce to translate the work he and his collaborators are doing to help chronically ill children.”

Team approach

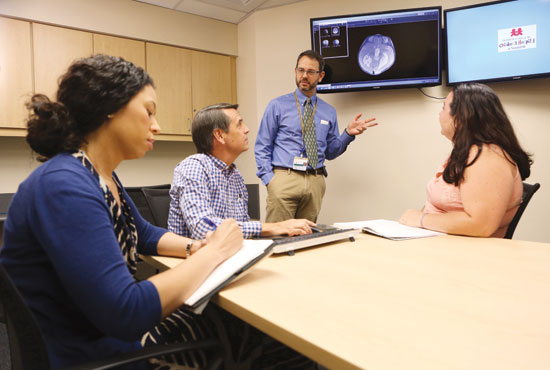

Surgical Outcomes Center for Kids (SOCKs) is a unique clinical research collaborative formed two years ago at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt by research associate professor Chevis Shannon, pediatric brain surgeon John “Jay” Wellons, and a team of physicians and researchers.

The partnership was designed to incorporate the voices of researchers into everyday clinical activities, refine and standardize protocols for care and improve patient outcomes.

Compas and his team of 35 researchers, including graduate and undergraduate students, make up the neuropsychology collaborative for SOCKs.

When a child is diagnosed with a serious medical condition, like a brain tumor, Compas and his team are called in right away to meet with the family to offer cognitive testing and ongoing evaluations to support the child’s learning throughout their medical journey.

“It’s a difficult time for the family, but we let them know we will be part of the care team and our focus will be on supporting their child’s learning,” Compas says. “With SOCKs, we gather around a table with researchers and clinicians to discuss the patients’ needs and bring our expertise to the discussion. It’s a proactive way of approaching and mitigating neurocognitive deficits, and we have better insight as a team than if we were all approaching it from our separate siloes.”

“I’m not certain that the field has been doing a great job of paying attention to … the overall effect of the treatment paradigm on how a child learns.”

—John “Jay” Wellons, VUMC chief of pediatric neurosurgery

Wellons says the collaboration with Compas and the SOCKs team has quickly become an important part of his practice.

“When I arrived in 2012, it was substantial to be greeted at the door by a man of Bruce’s reputation and research acumen,” says Wellons, professor of neurological surgery and pediatrics and chief of pediatric neurosurgery. “To be able to get our patients to him so he can assess them before and after surgery is significant. I’m not certain that the field has been doing a great job of paying attention to this piece—the overall effect of the treatment paradigm on how a child learns. That is something we need to be considering.”

Wellons says the collaboration has influenced his approach to treatment as well.

“As surgeons, just about our only concern has been to get as much of the tumor out as safely as we can, particularly if it’s malignant,” he says. “Now we have a team that works with us to look at all the variables so we can set up the patient to have the best outcome for cognition down the line.”

Paving a new future

Michael R. DeBaun, who holds the J.C. Peterson, M.D., Chair and is a professor of pediatrics, is an internationally recognized expert on sickle cell disease, a condition marked by a lifelong battle with chronic pain, hospitalizations and the threat of stroke.

“Stress is an important aspect of any chronic disease, particularly sickle cell disease,” says DeBaun, who serves as vice chair for clinical and translational research. “The novel early findings that Dr. Compas and his team have uncovered may provide us new tools to help children and adolescents with sickle cell disease cope with their condition.”

“(These findings) may provide us new tools to help children and adolescents with sickle cell disease cope with their condition.”

—Michael R. Debaun, VUMC vice chair for clinical and translational research

Debra L. Friedman, who holds the E. Bronson Ingram Chair in Pediatric Oncology and directs the Division of Pediatric Hematology–Oncology at VUMC, credits Compas with helping to provide a greater understanding of the stress cancer takes on her patients’ ability to learn.

“We are fortunate that we are able to cure 80 percent of children with cancer, but a cure is not enough,” Friedman says. “This relationship between pediatric oncology and psychology is essential but often absent in many programs. We now understand the issues better and are working together with Dr. Compas to develop interventions to improve quality of life for all.”

“We are developing better solutions together than we could have on our own.”

—Debra Friedman, director, VUMC Division of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology

As medicine continues to improve survival outcomes for children with serious health conditions, Compas says it will be important for psychology researchers to partner with health care providers, schools and legislators to build a support system for these young survivors so they can go on to higher education and meaningful careers.

“What my collaborators and I have in common is that we care about the welfare of children, and we know that the world is not a level playing field,” he says. “We need for all children to have the accommodations they need to do well in the classroom and in life, and that means a broader definition of learning deficits. We have identified the problem, and as we partner across disciplines we are developing better solutions together than we could have on our own.”