The first time a colleague questioned Ebony McGee’s intelligence she brushed it off. As one of the only black female engineers in the company, she knew she’d have to prove herself. But years later, the jabs hadn’t stopped.

One day at a staff meeting at Hewlett-Packard, a colleague was making a PowerPoint presentation. Suddenly in the middle of the talk, the presenter stopped and called her out. “Did you get that, Ebony? Do you need me to repeat that for you?” Earlier that week, McGee had been part of the team that put the presentation together, so the comment stung. Unfortunately these types of humiliations were commonplace.

“I had the education and the knowledge to do the job as well as anyone, but the people in my department would frequently address me as though I didn’t understand simple engineering concepts,” McGee said. “Back then, I didn’t have the language to describe what was happening or the tools to deal with it. I didn’t know if it was because I was a black woman or because I was a black woman who also attended a historically black college. I just knew it made me miserable.”

Facing Roadblocks

As a child growing up on the south side of Chicago, McGee didn’t yet know the recently popularized term “micro-aggression,” loosely defined as an unintentional slight or snub motivated by bias or racial profiling. She was excelling in her math and science classes and quickly went about earning an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering and a master’s in industrial engineering, twice graduating summa cum laude. McGee was ready to be an engineer, or so she thought. What she wasn’t prepared for was the unequal treatment she would face as a black woman in her chosen profession, which is dominated by white males.

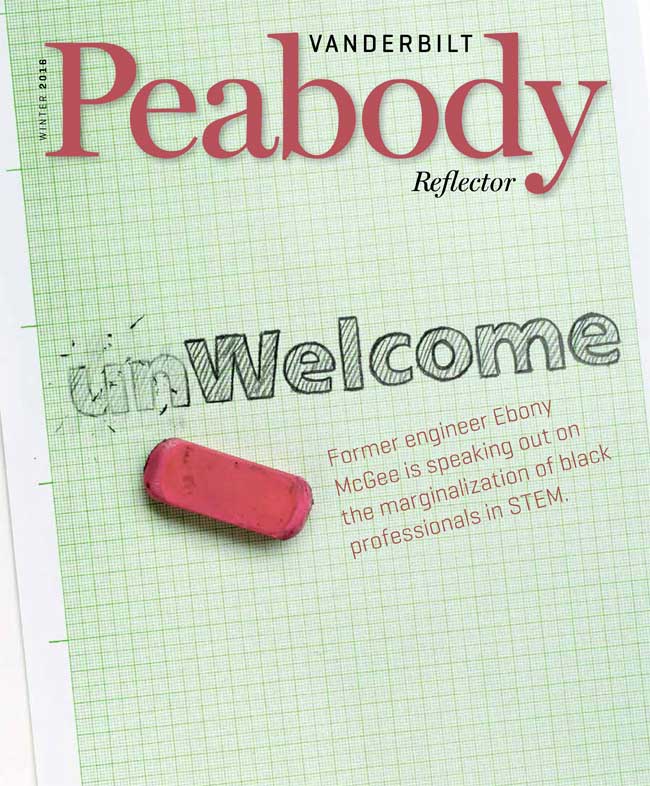

McGee worked at prestigious firms like Ford Motor Company and Hewlett-Packard in competitive intelligence, analyzing and measuring the advantages of competitors’ products. But being a double minority—female and black—she regularly found herself bumping into invisible walls that delivered the not-so-subtle message: “You’re not welcome here. You’re not good enough.”

“When you are the only engineer who is black and one of the only women, it can be quite isolating.”

—Ebony McGee

Worse, she didn’t want to let down her family and friends back home in Chicago. “My family and friends applauded me for achieving the American dream—an education, a great job, good money—so I felt very guilty about not being happy.”

A New Beginning

After several years of struggle, McGee was included in a round of layoffs, giving her some time to take a hard look at what she wanted in life.

“I actually was relieved—it gave me a chance to reinvent myself,” she said. “I love engineering and mathematics. And I understand the struggle people of color experience in this field. It was important to me to do something that would positively impact others’ lives. So I took a leap of faith.”

McGee enrolled in the doctoral program in mathematical education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her goal was to better understand the cultural constructs she had been at odds with and how they might affect other young black professionals in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.

She completed her doctorate in 2009 and came to Peabody in 2012 as assistant professor of education, diversity and urban schooling in the Department of Teaching and Learning. Since then, she has secured more than $2 million in grants from the National Science Foundation for her research on minorities in STEM.

She has published articles in top academic journals and presented at leading conferences, and was honored by the American Educational Research Association with the 2015 Scholars of Color Early Career Contribution Award. She also was among eight Vanderbilt professors named in INSIGHT Into Diversity’s “100 Inspiring Women in STEM.”

McGee’s timely research is striking a chord with academics as well as the press. She turned her sights on the professoriate with her published paper, “Entertainers or Education Researchers? Challenges Associated With Presenting While Black.” The paper, published by Taylor and Francis last fall, details a recent study in which she examined the experiences of 33 black professors at institutions across the country, including the Ivy League, when presenting research to colleagues.

Nearly across the board, they reported being advised by white professors to “lighten up” and “tell more jokes” when presenting their research. Black women, particularly, were subject to overt criticism of clothing and hairstyle, and told to play down their passion and “try not to sound so angry.” The study prompted an international discussion about micro-aggressions, from Inside Higher Ed to The Huffington Post to the BBC.

“Ebony McGee has been able to use her interview-based research to talk about stereotype management strategies,” said Rogers Hall, chair of the Department of Teaching and Learning. “That’s a novel and really promising approach.”

McGee’s next project is a $1.4 million National Science Foundation study that will examine how and why women in engineering persist despite barriers to success. In the three-phase study, McGee and colleagues at Purdue University will gather and analyze data from tenure-track female faculty members at about 350 accredited engineering institutions. They also will implement a national survey exploring issues of race, class and gender among women faculty in engineering.

“This study will allow us to further delineate how racism and classism manifest within academia and how women are persisting and succeeding in the face of these structural barriers,” McGee said.

Diversity in the Spotlight

Dovetailing with McGee’s research is a renewed focus on diversity and inclusion at Vanderbilt.

“It is the most important thing I’m going to be spending my time on,” Chancellor Nicholas S. Zeppos told faculty last fall. “We have to realize that…there are so many people who are at the periphery and they feel marginalized. It’s not as welcoming as you might think at the core, and we need to work on that.”

In December, Zeppos named biomedical researcher and diversity advocate George C. Hill to serve as Vanderbilt’s first chief diversity officer and vice chancellor for equity, diversity and inclusion. Hill will provide leadership in cultivating an inclusive, diverse and equitable academic community. Soon after, Peabody named Monica Robinson-Nichols associate dean for students and equity, diversity and inclusion.

Zeppos also selected McGee to serve on a 15-person committee to work on issues of inclusion, diversity and community at Vanderbilt, along with fellow Peabody faculty Anjali Forber-Pratt, assistant professor of human and organizational development; and Donna Ford, professor of special education.

These positive steps build on the newly formed Inclusion Initiatives and Cultural Competence effort at Vanderbilt, which was formed to help students develop the skills necessary to promote social justice and have constructive conversations surrounding differences.

McGee believes this intensive focus has occurred none too soon and was encouraged by Zeppos’ call to action. “It was radical for a chancellor to say that if we aren’t addressing racial challenges, we are failing as an institution. You don’t often hear administrators talking about race in such a conscious way,” she said. “It’s not just about recruiting faculty and students of color, which we need to do. It’s about what happens once they get here.”

Zeppos is equally complimentary of McGee. “I have a deep appreciation for the extraordinary things Dr. McGee is doing to champion an environment that focuses on academic resilience among minority students,” he said. “Her thoughtful perspective, background and experiences bring insights that are often missing in discussions about our role as a university—and our faculty’s role as mentors and sounding boards for concerns about institutional racism, individualized racism, and the barriers these attitudes erect for minority students.”

Welcoming Spaces

McGee is mindful of the work required to shift a cultural paradigm but is pleased to be positively affecting the STEM field, starting with the culture at Vanderbilt and at Peabody.

“To be culturally affirming, it takes more than food and festivals—you really need to change the dynamic of the climate,” she said. “It’s up to the institution to know what their students and faculty of color are experiencing and provide programs and training so that people aren’t perpetrating these racialized experiences on already-taxed black and brown students and faculty.”

McGee recommends implicit bias training so that faculty, staff and students can become more aware of the racial biases and stereotypes they may possess, and learn how those contribute to institutional racism.

“People don’t want to believe that micro-aggressions have the power to alienate and hurt,” said McGee.

“I hear nonblack students say to a black student, ‘You don’t sound black,’ or ‘Your outfit is so ghetto’—and I can tell you firsthand when you are the only black girl in the room, those kinds of comments hurt.”

—Ebony McGee

“Exploring topics like racism and white privilege can be emotional, awkward and draining, especially if only minoritized people are tasked with heading talks about inclusion and diversity. That’s why it’s necessary to have cross-cultural conversations where people of all races can openly and honestly discuss issues and work together for change,” she said.

McGee also advocates creating racially affirming spaces where people of color can get together, share their experiences and support each other.

“The chancellor has said that now is the time for Vanderbilt to diversify both the faculty and the student body,” Hall said. “We’re going to need concrete strategies, and I think Ebony is the right person to give us some.”

Equipping the Next Generation

McGee devotes much of her time to mentoring black students and equipping them for the workplace. She recently started an online portal (blackengineeringphd.org/mentoring) that acts as a gathering place for black undergraduates and graduate students pursuing STEM.

At the site, visitors can peruse research findings and access resources on dealing with micro-aggressions, tips and strategies for securing an academic position, and personal narratives of black professors. It also provides a safe space for students of color, particularly those in the STEM disciplines, to build a sense of community, sound off and share their struggles.

“It’s about making students aware that there are things that they may experience in their career trajectory that aren’t necessarily unique to them,” said Stacy Houston, a doctoral candidate in the sociology department, who assists McGee with her research. “I think that if we can figure out how to answer the questions about why we aren’t seeing many black and brown faces in STEM and the professoriate, it can go a long way in helping students in all disciplines follow their dreams and not get discouraged,” he said.

Lydia Bentley, a doctoral student in the development, learning and diversity track of the Department of Teaching and Learning, counts McGee as a mentor.

“Before I met Dr. McGee, I didn’t know anyone who was concerned with these kinds of things. She’s given me a new vision of how there is room for me to become a professor and study these things too”

—Lydia Bentley

In just a few short years, McGee is beginning to see a shift in the fabric of the world around her—not only at Peabody, but across institutional lines at Vanderbilt, and in the public consciousness. There is a long way to go, but many reasons to be hopeful, she says:

“My hope and optimism lie with STEM researchers, educators and employers who every day are forming a new appreciation and acceptance of the brilliance of all students and professionals—including the ones who are so often not assumed to be so.”