I Learned to Ask for Help—and I’m Still Asking

By Mallory McDuff, BS’88

Dear Dr. Vereen Bell,

Thirty years ago, as a freshman, I sat in the second row of your Modern American Novel course. Every weeknight I studied in the library until closing time and then returned to my dorm room, where I listened to two girls on my hall sing Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” after a late night at the bars.

With a bit more free time on their hands than I, the Madonna girls also were more prepared for college. They attended well-funded high schools with SAT tutoring and robotics clubs, while I graduated from a public high school in Alabama with caring teachers but sparse resources.

As the valedictorian of Fairhope High School, I spearheaded fundraisers to buy computers for our school, organized Halloween dances for adults with cognitive disabilities, and motivated teams of students to sanitize the funky bathrooms. In high school I tried to save the world. In college I needed to save myself.

Within the first week of college, I realized that what I lacked in academic preparation I would have to overcome through persistence. So I befriended the geeks on my hallway, adopted a library carrel as my own, and then chewed my cuticles when you passed out grades for our first paper on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

The structure of your Modern American Novel course involved reading one book every week for the semester, including classics like Native Son, The Great Gatsby and Song of Solomon. Each week you gave us the option to write a two-page essay about the book. While I can’t recall the exact number, an average of the highest six or so papers determined the final grade, in addition to weekly quizzes.

We could take a risk and only write six papers. Or we could adopt the conservative approach: Read each book, and write an essay about each one. It was a game of probability, if nothing else.

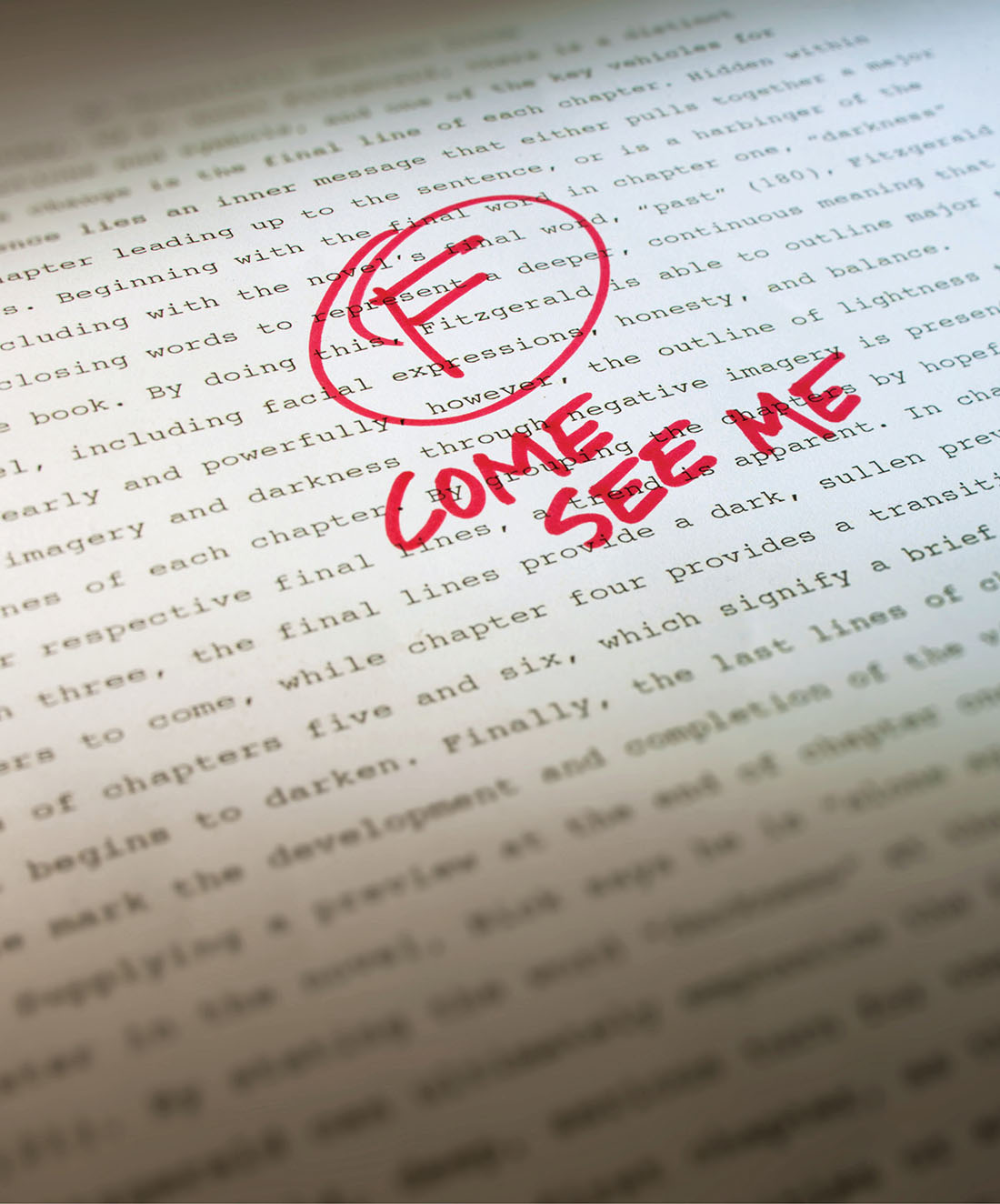

Wearing spectacles, a tweed jacket and a wry smile, you stood in front of the classroom and called out names, folding each paper in half with a flip of your wrist, in a gesture that concealed both the grade and your written comments. When you called my name, I reached for the paper and saw one question facing me, an interrogation I will never forget: “Where did you learn to write like this? Come see me.”

One question. One sentence. Eleven one-syllable words in a line. And underneath those comments was one letter: F.

My cheeks burned red, and my breath shortened, as if I had a sudden case of asthma. Still holding the paper in my hand, I left the classroom and practiced deep breathing all the way to the freshman quad.

Back in the dorms, I kept my F to myself.

At that age, I was both scared of failure and skilled at following directions. So the next day I made an appointment to see you and walked into your office, a cavernous room with ceiling-to-floor windows. I remember your office as a palace on campus, much like a child imagines a wilderness in a tiny backyard.

In our meeting I don’t recall what you taught me about the structure of a critical essay. But you told me that if I wrote about every novel and brought the paper to you before the due date, you would give me feedback for revision.

You gave me a way out. And I followed. Wasting no time, I brought you every single essay, followed by the revised version. I typed and re-typed on an IBM Selectric, with a bottle of Wite-Out at my side.

For the first time, I learned about the power of revision. And at the end of the semester, you averaged the highest six grades of the semester: I got an A- in the class.

Where did I learn to write? I didn’t learn to write in one semester, but I learned to ask for help—and I’m still asking. After that revision boot camp, I became addicted to feedback, an unusual dependence for a student. For the rest of my college career, I submitted papers early, revising them before the due date, sometimes out of insecurity as much as necessity.

Dr. Bell, you taught at Vanderbilt more than 50 years, after arriving in the 1960s, advocating for diversity in the department, marching for civil rights in Nashville. In an issue of Vanderbilt Magazine, one of your colleagues described you as a “brilliant and caring teacher, a productive and admired scholar, a supportive if sometimes provocative and crabby colleague, a witty and refreshingly naughty presence around the department.”

I can’t speak to the “naughty” part, but as a college professor today, I don’t have the guts to write on a student’s paper, “Where did you learn to write like this?” I’m afraid of phone calls from parents or nasty comments on course evaluations. But I am not afraid to require students to come see me, to submit their papers early, to visit tutors at the writing center. While my office doesn’t look like yours, I am living and reliving that moment in your office 30 years ago.

“Come see me,” I write on their papers, and we learn the power of revising our words, together.

Yours truly,

Mallory

Mallory McDuff, BS’88, is a professor of environmental studies and outdoor leadership at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina. Her essays and op-eds have been featured in USA Today and The Huffington Post. Find out more at mallorymcduff.com.

Vereen Bell, professor of English, emeritus, retired in 2013 after 52 years of teaching at Vanderbilt.