Each day we are bathed in thousands of man-made chemicals that never existed in nature. They are in cosmetics and shampoo, food packaging and plastic containers, clothing and building materials, furniture and electronic devices.

Although the U.S. now produces more than 500 million tons of synthetic chemicals annually, a major “toxicological information gap” has developed regarding the risks they pose to human health and the environment. According to a number of government reports, less than 10 percent of the 80,000-odd chemicals in general commerce have been tested adequately to determine their health risks.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has announced the establishment of three new centers to develop alternative approaches for toxicity testing that could help fill the troubling gap. One is the Vanderbilt-Pittsburgh Resource for Predictive Toxicology (VPROMPT), which will receive $6 million for four years to develop toxicity test procedures based on three-dimensional human cell cultures, rather than the combination of standard two-dimensional cell cultures and whole animal testing that has been de rigeur until now.

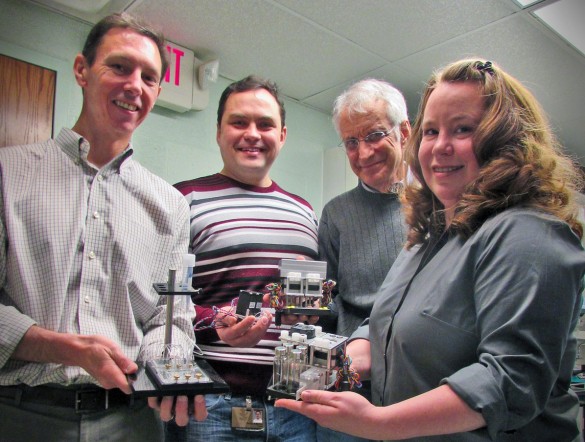

VPROMPT is a collaboration between investigators at Vanderbilt University and the University of Pittsburgh. The lead principal investigator is M. Shane Hutson, associate professor of physics at Vanderbilt. The five co-principal investigators are Research Associate Professor Lisa McCawley, Professor Kevin Osteen, director of the Women’s Reproductive Health Research Center, and Gordon A. Cain University Professor John Wikswo at Vanderbilt and Rocky Tuan, director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering, and D. Lansing Taylor, director of the Drug Discovery Institute, at Pittsburgh.

“[lquote]Given the situation we face, traditional toxicology testing procedures are simply inadequate[/lquote],” said Hutson. “A full toxicological evaluation for a single chemical using traditional methods can cost millions of dollars, involve hundreds of test animals and take years to complete. And, as if the time and cost weren’t bad enough, existing tests haven’t proven very good at predicting chemicals’ effects on humans.”

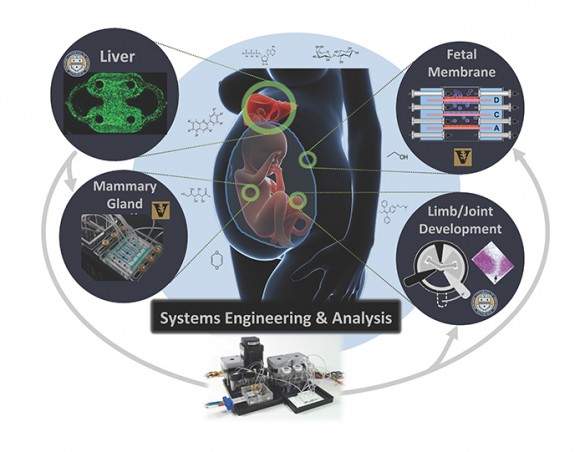

The primary goal of the new center is to develop a series of 3-D human cell cultures that are heavily wired up with different sensors to record how they respond when exposed to small concentrations of potentially toxic chemicals. The forefront of cell biology is moving away from traditional 2-D culture of a single cell type towards 3-D cell culture of multiple cell types that more closely mimic the microenvironment of particular organs. These more complex cultures exhibit cell behaviors that are much more like those seen by cells in living animals. By making sure the cultures use human cells, the researchers hope to avoid misleading toxicity results caused by differences in how animal and human cells respond to the same chemical.

“We are very excited about the new Vanderbilt/Pittsburgh partnership to develop and apply innovative tissue-on-a-chip technologies to identify and evaluate potential harmful agents in the environment, and contribute towards improving the nation’s health,” said Tuan.

The researchers will develop four test platforms: one using liver cells; one using fetal membrane cells; one using mammary gland cells; and one using cells involved in limb and joint growth. They selected the liver because one of its functions is to remove toxic substances from blood coming from the digestive system before they can spread throughout the body. The fetal membrane and mammary gland cells were included because of the roles they play in reproduction. And they choose the cells involved in limb and joint growth because their role in development.

The researchers will expose the 3-D cultures to a battery of previously identified toxic chemicals that have been extensively studied using traditional methods so they can compare the results and determine how well the procedures they have developed predict the results of the older tests.