Marriage tells us a lot more about employment status around the world than we thought

For decades social scientists described how being both foreign-born and female was a “double disadvantage” on a person’s likelihood to have a job in the United States. New Vanderbilt research shows that where you’re born doesn’t matter nearly as much as whether you’re married and a woman.

Katharine Donato, professor and chair of sociology, and graduate students Bhumika Piya and Anna Jacobs were invited to present their findings at the International Migration Review 50th Anniversary Symposium in New York City Sept. 30.

The “double disadvantage” concept has been a popular way to understand women’s labor force participation since it was first described in the International Migration Review in 1984. But as more census data and more tools to crunch it have become available, Donato and her students set out to dig deeper into the phenomenon. First, they reexamined the double disadvantage in the United States case, and then did something new: They factored marital status into the equation. Then they studied whether double disadvantage—marital or otherwise—existed in a number of other immigrant destination countries: Brazil, Venezuela, Canada, Spain, Greece, Israel, South Africa and Malaysia. They found that it looks very different in other countries.

Revisiting the “double disadvantage” in the United States

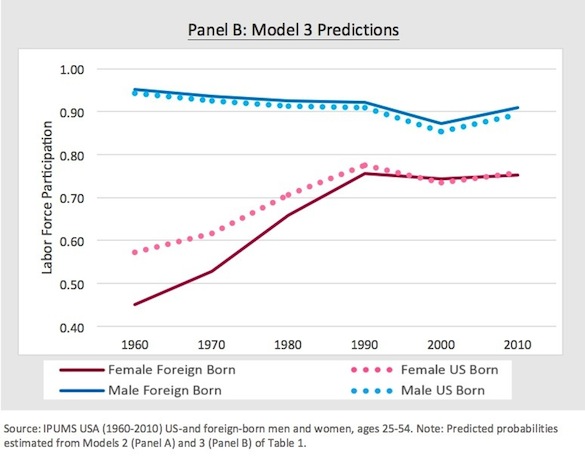

Using census and other demographic data from 1960-2010, the researchers first looked at how gender and nationality translated to labor market participation in the United States. Using multivariate statistical modeling that controls for other relevant variables, they found that foreign-born women were indeed less likely to have a job than native-born women for the first half of the study period. By 1990, however, foreign-born women were working just as much as native-born women—and even though their labor force participation remained lower than men’s, immigrant women’s disadvantage had disappeared.

Meanwhile, foreign-born men were slightly more likely to work than native-born men, and this held true for the entire 1960-2010 period. On the whole, the labor force participation rate of all men averaged about 90 percent throughout the study, while the rate of all women rose to about 75 percent in 1990 and hasn’t varied much since then.

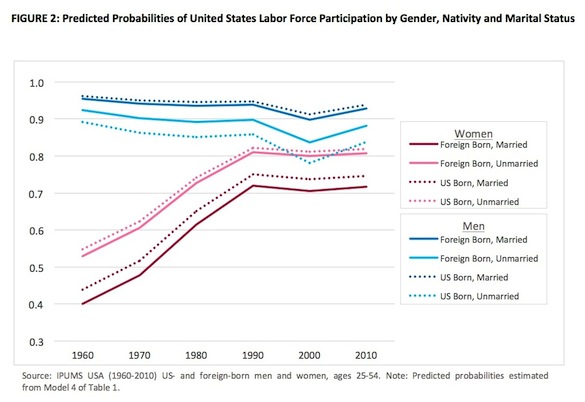

But when the researchers added marital status into their statistical models, the picture changed significantly. After accounting for other relevant factors, among both immigrants and natives, married men had higher rates of employment than their single peers, but married women had significantly lower rates of employment than single women. The researchers were surprised to discover that marital status made a much greater difference in a person’s likelihood to be employed than whether they were immigrants or U.S. natives. “This is something we didn’t know before,” Donato said.

In all cases but one, being U.S.-born conferred a small advantage. The exception is for single immigrant men, whose labor force rates are significantly higher than U.S. born unmarried men.

In fact, being U.S.-born, single, and male was associated with one striking disadvantage: In 2000, the employment rate of single U.S.-born men was equal to or slightly lower than that for single immigrant and U.S. born women. That disadvantage didn’t last very long, however, and even at their lowest point these men still worked significantly more than married women.

In the United States, then, the true double disadvantage isn’t being foreign-born and female, it’s being married and female.

The double disadvantage looks different in other nations

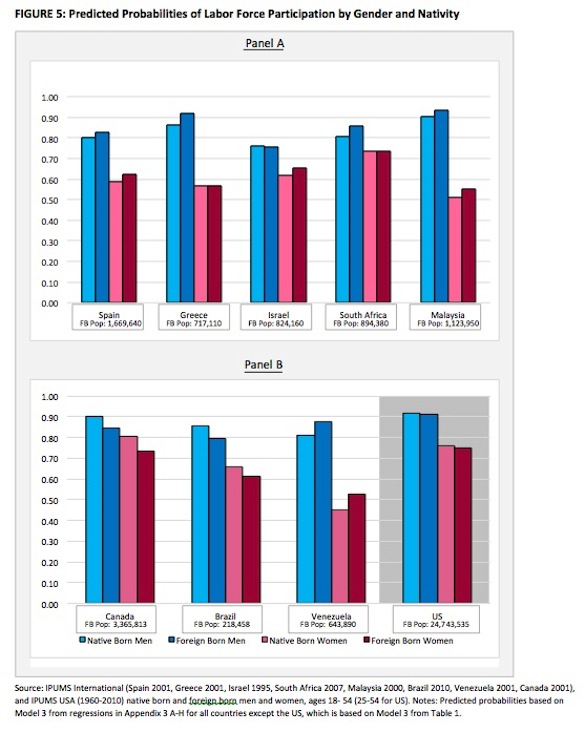

“Migration has become a much more globalized experience,” Donato said. “So we thought, ‘Let’s look at other immigrant populations around the world.’” And they found that the pattern looks very different in other countries. Examining the most recent census data for each country, they found that in every case, men (married and single) have higher rates of employment than women (married and single). In Brazil and Canada, native-born workers have a clear advantage over foreign-born ones—classic examples of the double disadvantage as it has been understood for the past 30 years.

But in Malaysia, Venezuela and Spain, the reverse is true—foreign-born workers are more likely to be employed than native ones. In Israel, nativity doesn’t have a very strong effect on the employment rate of men, and in Greece and South Africa it has almost no effect on the employment rate of women.

How marriage affects the double disadvantage in other nations

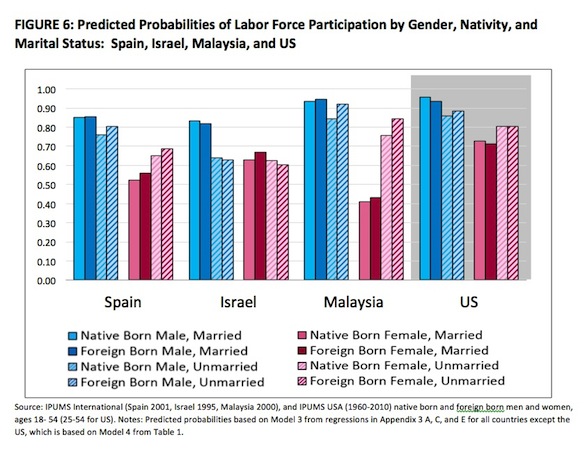

The researchers then dialed in further and found that marriage helped explain these findings for Spain, Israel and Malaysia, compared those findings to the United States.

In Spain, married men – whether immigrants or natives – had similar employment rates and participated in the labor force more than either group of single men. In addition, foreign-born single men reported more labor force activity than native-born single men. Yet, among women in Spain, single foreign-born women worked the most, followed by native-born single women, then foreign-born and native-born married women.

In Israel, native-born married men, followed by immigrant married men, worked more than their single peers, whose employment rates were similar to married and unmarried native-born and immigrant women.

Of all the countries Donato and her team studied, marriage was the most significant stratifier for women in Malaysia. Although men’s labor force participation differed very little across nativity and marital status groups, married native- and foreign-born women worked significantly less. However, unmarried women’s participation rates were much higher, with single foreign-born women working almost as much as single native-born men.

Looking forward

“Our next step,” Donato said, “is to consider how the onset of marriage and the timing of migration help explain these differences.” Before doing that, however, Donato and her team are studying how the double disadvantage might play out for immigrants of different national origin groups in a wide variety of global destinations and for immigrants of different race groups in the United States.

The researchers also plan to look at the effect that immigration status has on nativity, gender, and marital status differences in employment, as well as the effects all of these factors have on job quality as measured by prestige and wages.