When the Common Core State Standards initiative was introduced in 2009, the idea of adopting a rigorous new set of educational standards for K-12 schools in all U.S. states struck a positive chord with educators, researchers and parents.

There was no disagreement that states needed to have uniform standards, and that students needed to be better prepared for college and career in an ever-more competitive global marketplace.

Unlike previous educational initiatives like No Child Left Behind, Common Core was not a government-mandated reform.

A grassroots effort buoyed by like-minded activists, education groups and powerful business leaders, the movement benefited from a promotional campaign financed by Microsoft mogul Bill Gates and others and the support of the Obama administration.

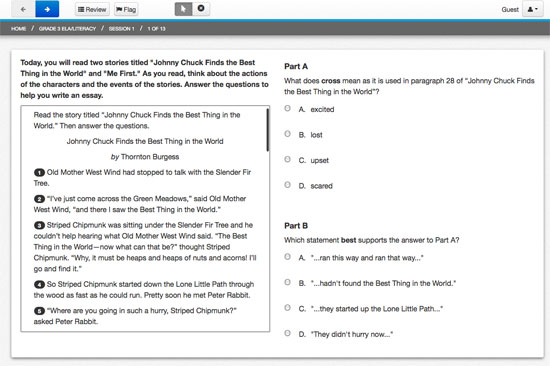

The newly crafted set of standards in math and English/language arts did not prescribe a specific curriculum, but promoted a streamlined set of objectives for each grade level and a new approach to pedagogy that moved students away from rote memorization toward problem-solving, critical thinking and spatial reasoning. In addition, Common Core shifted emphasis from traditional standardized testing to two new computer-based assessment consortia specifically aligned with the spirit of the new standards.

“It is a trajectory of learning that has no empirical basis.”

—Lynn Fuchs

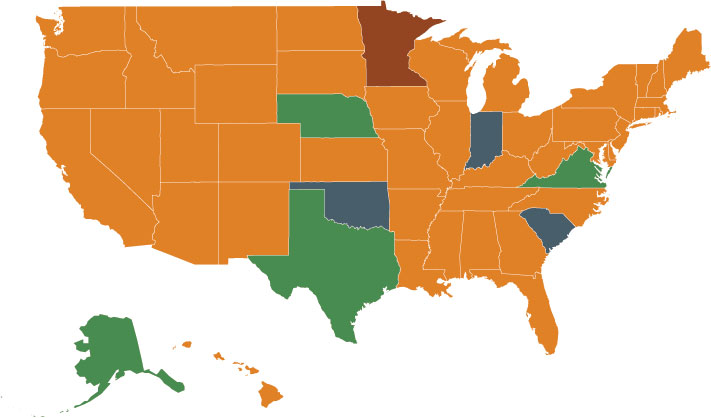

Soon after Common Core was introduced, 45 states voluntarily adopted the standards, with high hopes for a fresh new reform in American K-12 education.

However, five years later, implementation is hitting roadblocks and enthusiasm has lagged. The once bi-partisan enterprise has become a political tug of war, with grassroots conservatives branding it an example of federal overreach. Detractors say government funding enticed states to adopt too quickly what is essentially an experiment—no one knows for sure if Common Core will have a successful outcome.

Organizers of Common Core say it simply needs more time to play out. But vocal opposition maintains this “reform” could cause more harm than good if left unchecked. In recent months, three states that had adopted the standards have pulled out.

That leaves the education community to ponder: Does Common Core need a course correction?

Common Core: In the Beginning

The Common Core State Standards initiative was born in December 2008, three months after Lehman Brothers collapsed, in what would come to be known as “the Great Recession.” George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 had expired, with Congress failing to enact a new version of the bill. President Obama issued waivers to relieve states of the act’s requirements.

With education reform stagnating, the National Governors Association, the Council of Chief State School Officers and Achieve, Inc., issued a report emphasizing the dire state of the U.S. education system, Benchmarking for Success: Ensuring U.S. Students Receive a World-Class Education.

The report was driven by a multitude of concerns. States varied widely in what was expected of students. A fifth-grader in Florida was not necessarily being taught the same educational benchmarks as a fifth-grader in Minnesota or California. College readiness statistics also were troubling. An estimated 27 percent of all students under 25 at public four-year colleges, and a whopping 44 percent at two-year colleges, were taking at least one remedial course, according to U.S. Department of Education statistics.

There was also the nagging reality that U.S. schools were not competing at the global level. One international measure, The Programme for International Student Assessment, placed American students at 31st in the world in math, 23rd in science and 17th in reading. The United States was being outpaced by top performers China, Singapore and Japan, and trailed smaller nations like Finland, Latvia and Azerbaijan. Raising academic standards that would prepare students to be innovators and leaders became the battle cry.

The report quickly gained political support on both sides of the aisle, along with a wide variety of education stakeholders. In 2009, Gates and others spent millions researching and outlining the standards, and educating lawmakers, teachers and school administrators on what would be known as the Common Core State Standards initiative. That same year, President Barack Obama and education secretary Arne Duncan announced the $4.3 billion Race to the Top grant program, which rewarded states for, among other things, adopting the Common Core. Forty-five states voluntarily adopted the standards in short order. Since then, politicians, parents, educators and researchers have debated the efficacy of the latest attempt at K-12 education reform in America.

A New Way of Teaching

Most agree the idea of standardized learning across the states is a lofty, yet necessary goal. How to accomplish that is another question. At Peabody, opinions on Common Core are as mixed as elsewhere in American society.

“It is a trajectory of learning that has no empirical basis,” said Lynn Fuchs, Nicholas Hobbs Professor of Special Education and Human Development. “We don’t know yet whether it makes sense to have this particular set of standards. We don’t know if it produces something better or even different from what it was before.”

The ultimate outcome remains to be seen, but the focus on teaching students to move beyond memorization to thinking independently and creatively is a positive step—at least in theory, according to Marcy Singer-Gabella, professor of the practice of education and associate chair of the Department of Teaching and Learning.

“American schools are failing. But Common Core can challenge that narrative.”

—Barbara Stengel

“Granted, the standards are rigorous and it will take a tremendous effort to reorganize ourselves to support children in achieving them, but they position students as agents, as learners, as inventors and as creators of meaning,” Singer-Gabella said.

Barbara Stengel, director of secondary education, also supports this intuitive approach to learning.

“The narrative is that American schools are failing,” Stengel said, “but I think Common Core can challenge that narrative. Peabody faculty have been educating teachers to develop creative and critical thinking in students all along, and no Peabody College graduate would find this concept of teaching alien.”

“It’s the way good teachers have always taught,” added Joseph Murphy, Frank W. Mayborn Professor of Education.

But the new curriculum teachers have developed in response to Common Core has produced confusion and dismay on the part of some parents. A quick perusal of social media sites reveals numerous posts about Common Core worksheets that seemingly defy logic.

“Draw the word, ‘Nobody.’ That doesn’t make any sense,” one parent tweeted. Another added: “Kids can’t learn 6 x 8 = 48 anymore—it’s now 6 x 8 = (5+1) x 8. Why the confusing work?”

The standards push teachers to approach topics from a different pedagogical stance. Under Common Core, a third-grader should be able to recognize “area” as an attribute of two-dimensional regions, be able to decompose it into units, and explain why multiplication is an appropriate tool to determine area. But is a 9-year-old ready for such complex thinking?

Singer-Gabella says yes.

“It’s the way good teachers have always taught.”

—Joseph Murphy

“One approach to helping students develop this kind of conceptual understanding is to engage them in tasks that let them visualize and play with these relationships,” she said. “Let’s say you have some rabbits and 18 feet of fencing, and you want to build a rectangular pen that gives the rabbits as much room to run as possible. How long would the sides need to be in order to maximize area? This problem asks the student to think about length, perimeter and area in relation to one another, and can’t be solved just by memorizing and applying a formula.”

Similarly, in language arts, even in early grades, students are expected to discuss the nuances of a text, its historical and literary context and assess the author’s background and motivations. As with the math standards, this approach goes far beyond simply performing at grade level. It requires a teacher to engage students in discussion, debate or role-playing—in fact, anything that works. That may mean a noisier and more dynamic classroom in which students move around, pair up and utilize tools to problem-solve. Teachers will be pushed to go outside of their typical teaching modes.

Stengel says the spirit of Common Core is in keeping with the Peabody approach. “We teach our candidates how to pull out what students are already thinking, what they already know, and then how to build on that so everybody learns, and that they’re learning from each other as well as the teacher,” she said. “The goal is not simply procedural fluency or achievement but rather deep disciplinary understanding, and beyond that, thinking for oneself.”

The Struggle to Implement

Because the standards do not mandate a specific curriculum, teachers must design instructional strategies to achieve the ambitious goals of Common Core and prepare students for the new year-end tests, which could be daunting, according to special education professor Doug Fuchs.

“Common Core mandates what, but not how,” said Fuchs, Nicholas Hobbs Professor of Special Education and Human Development. “Common Core makes the point of not dictating the instructional methods by which this will be achieved. They’re just saying what you have to produce.”

“It’s a different level of curriculum,” Lynn Fuchs said, adding, “What teachers are going to have to do is teach their students how to provide explanations.”

“Common Core mandates what, but not how.”

—Doug Fuchs

The Fuchs recently earned a $10 million grant from the National Center for Special Education Research to develop new math and reading strategies aimed at improving student success. The five-year grant will enable the researchers to study instructional programs targeting third- through fifth-graders with the most severe learning disabilities.

“In math, we are addressing fractions, decimals and beginning algebra, which are all reflected in the Common Core standards,” she said. “In fractions, for example, we emphasize being able to appreciate the magnitude of fractions and understanding deeply what fractions are about.”

Stengel, too, is putting the critical thinking approach to the test in her research. She is working to engage both high- and low-performing students at Bailey Middle School in Nashville. Stengel and Peabody master’s degree students, with the support of Principal Christian Sawyer, also a Peabody graduate, have taken a team approach: Ten teachers work with 120 students in shifting configurations based on performance, curriculum, behavior and any other factors that require attention.

“We are building understanding and autonomy in these students,” Stengel said.

Children Left Behind?

Common Core may serve the typically developing students, but it will likely fail the students who already lag behind, according to Lynn Fuchs. At risk are children reading below grade level, those who are living in poverty, non-native English speakers and those with intellectual or developmental disabilities, she said. “For populations like these, it doesn’t help to make the standard so far removed from their grasp,” she said.

“Proponents say don’t worry … [they] are profoundly misinformed, or worse.”

—Doug Fuchs

It’s an age-old problem that comes with education reform, according to Doug Fuchs. “Proponents of Common Core will say don’t worry—we know how to accommodate those who need additional help,” he said. “The people saying that are profoundly misinformed, or worse.”

He cites three decades of research in the field of special education working with special-needs students in classrooms with typically developing students. “There is demonstrable evidence from nationwide evaluations of academic performance that literally millions of these children are learning nothing,” Doug Fuchs said. “So it’s not going to be the case that all or most are going to be able to succeed with Common Core.”

Murphy agrees. A former K-12 teacher, he has observed firsthand at-risk students falling behind, never to recover. Imposing across-the-board achievement demands on children who struggle could do more harm than good, he believes.

“I have watched students slowly die in front of me an unnecessary death,” he said. “They keep getting messages of inadequacy and deficiency, and they close down like a flower.”

For the past 25 years, Murphy said he has observed education reformers focus on two different streams: developing a rigorous curriculum; and creating a culture of support and engagement within schools.

“Neither can carry the ship alone,” Murphy said. “They wrap around each other. If you are not going to create a powerful culture of support, it’s not going to work for at-risk students.”

A New Measuring Stick

Standardized testing has long been a practice in education to assess how well students are learning and how well teachers are teaching. No Child Left Behind linked standardized test scores to teacher salaries, causing them to “teach to the test” rather than focus on deeper learning. Worse, states were responsible for developing their own testing, and many responded to poor student outcomes by making tests easier.

“If you are not going to create a powerful culture of support, it’s not going to work for at-risk students.”

—Joseph Murphy

Common Core supplants this paradigm with new student assessments that are computer-based, and interactive: Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers and the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium.

Early Common Core adopters, including Kentucky and New York, implemented the new assessments for the 2011-12 school year and saw drops in student scores by as much as 30 percent, according to an article in Scholastic’s Fall 2013 issue. Questions remain as to how long it will take for the assessments to adequately reflect Common Core’s viability.

This spring, more than 4 million students across the country field-tested PARCC and SBAC. Lower-than-expected scores are cause for concern, with some wondering if measuring progress for the next few years will be an exercise in comparing apples to oranges.

“The testing is very technology-driven,” Lynn Fuchs said. “When students are expected to provide explanations, you have to have a way to demonstrate learning on a computer, which has its own set of challenges.”

“The new measures will be helpful, but it remains to be seen if they will lead to good things,” Murphy said. “Trying to measure critical thinking is a difficult task.”

At press time, 15 states were committed to implementing PARCC; and 22 states and one U.S. territory had committed to implementing SBAC in the 2014-15 school year. A handful of states, including Tennessee, Arizona and New Mexico, recently chose to delay implementation of the new assessments. Some states are developing their own.

“If the assessments that the breakaway states adopt are less rigorous than those developed by Smarter Balanced or PARCC, then it is less likely that adoption of Common Core will lead to the fundamental changes in instructional practices envisioned,” said Thomas Smith, associate professor in the Department of Leadership, Policy and Organizations.

The next question is if states will adopt the Next Generation Science Standards, which will introduce rich K-12 standards for an internationally benchmarked science education. Although 26 states influenced their development, only eight have signed on so far.

What Next?

In this uphill trek, including criticism that teachers haven’t been involved enough in the planning and implementation of Common Core, there have been positive reports.

An independent survey conducted by the Tennessee Consortium on Research, Evaluation and Development, housed at Peabody, revealed that at the close of the 2012-13 school year, most Tennessee teachers believed that the implementation of Common Core was off to a good start.

“Our analyses found that (Tennessee) teachers generally believe that Common Core will change the way they teach and also result in improved student outcomes,” said Susan Burns, deputy director of the consortium. “Teachers also believe, however, that additional guidance and resources would be beneficial as implementation progresses,” she said. The survey was conducted again this spring, with results available later in the summer.

“These children will soon be adults who will influence our country and the world— it’s our job to pull together and get them there.”

—Barbara Stengel

The Gates Foundation released results of its own survey in March, revealing that of the 20,000 teachers surveyed nationwide, 75 percent feel prepared to teach the standards. Overall, 73 percent of teachers who teach math, language arts, science and/or social studies in Common Core states are enthusiastic about implementation in their classrooms, the survey said.

There is good news from the 2013 Nation’s Report Card, compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics’ National Assessment of Educational Progress. Reading and mathematics scores have steadily increased since 2011 among early Common Core adopters, especially Race to the Top winners Hawaii, Tennessee and the District of Columbia. All states that had adopted Common Core held steady or improved, the U.S. Department of Education announced in November 2013.

What’s getting lost in the Common Core debate, said Stengel, is the reason for this reform, and that’s to prepare young people to be the nation’s future leaders and innovators.

“In all the political grandstanding and rhetoric, I think we are forgetting the common goal of all this, which is to prepare our children to become powerful leaders, inventors, explorers, innovators and role models. These children will soon be adults who will influence our country and the world—and it’s our job to pull together and get them there.”