When My Dad Died Just Weeks into My Freshman Year, He Left Me a Priceless Legacy

By Sidney DeLair, BA’75

It was my first hello and my last goodbye.

As I stood by the green dumpster overflowing with boxes discarded by freshmen moving into the Kissam Quadrangle, I waved goodbye to my dad and mom while their blue 1965 Buick LeSabre slowly inched onto West End Avenue.

I had arrived on Vandy’s campus for the first time that hot August morning in 1969. I don’t remember how long I watched or whether I spent much time following my parents as they drove away. All I knew was that a great new adventure was opening up for me.

Six weeks later, in the middle of a weekday night, I received a phone call from my brother-in-law. My dad had died of a massive heart attack, pitching forward to land face-down on the greasy wooden machine shop’s blocks in the huge factory where he worked, the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors. He was 55 years old.

At first I didn’t know what to do next. One of the freshmen across the hall, Dennis Carrithers [BA’73], woke up and helped me pull my act together, an act of kindness that I am grateful for to this day.

I flew home for the funeral in Westmont, Ill. I remember very little of it. When I arrived home, my mother pulled out a worn silver pocket watch from Dad’s dresser drawer and handed it to me. I already had been told the story behind the watch many times, and I loved what it represented.

My dad, Stanley, was the oldest of seven kids. As part of a tenant dairy-farming family in Door County, Wis., it was my dad’s chore to milk the entire herd before going to school every morning.

When Stanley was about 10, his father, Henry, lost the pocket watch, his most prized possession. One morning while my dad was forking hay down to the cows, he heard a “twang.” There was his father’s pocket watch—with a pitchfork tine right through the middle.

Dad was aghast. He felt responsible for ruining his father’s most treasured possession. He secreted the watch in his pocket.

After school he walked 12 miles into Sturgeon Bay and entered a jewelry store. The jeweler, a man named Mr. Draeb, examined the dusty old watch and looked up. He had good news and bad news, he said.

“Tell me the bad news first,” my father asked.

“It’s going to cost you $3 to repair the watch,” Mr. Draeb said.

In 1924, to a 10-year-old lad who lived as a tenant farmer, $3 was a king’s ransom.

The good news was that the watch could easily be repaired. Dad was elated. He told Mr. Draeb that he received 5 cents per week to milk the adjoining two farms’ cows. It was money he had counted on to pay for his lunch every day at school. Now, though, he would return to the jewelry store every week to pay his 5 cents until the watch repair was paid in full.

For the next 60 weeks, my dad repeated his 24-mile round-trip journey, through the winter months of bone-chilling cold, returning faithfully each week to pay the watch ransom. The watch was finally paid off just before Christmas. By then Dad had turned 12.

On Christmas morning Henry opened a carefully wrapped package and found, to his amazement, his cherished pocket watch. “How could this be?” he asked.

My dad recounted the entire story for his father, who was pleased in so many ways. “Stanley, you now know the value of hard work,” he told his son. “And more important, you understand that if you put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything.”

Now, some 45 years later, my father was dead, and the watch was mine.

“Let this be a guide for you,” Mom said as she handed it to me. “This is how hard your dad worked to get you the opportunity to go to college, when he never had the chance. He was so proud of your attending Vanderbilt that he told everyone.”

A few days later I returned to Vanderbilt’s campus and the red brick walls of Reinke Hall. My grades plummeted. I was not interested in class or learning about anything. I was listless and unmotivated—both traits that were foreign to me. At the end of the semester, I think I had one passing grade: a D-minus.

I decided to remove myself from this environment and reconsider my life options. With Dad’s passing I had lost not only his wisdom and knowledge, but also my funding source. So I made the terrible decision to drop out of school.

I landed a job working for my uncle’s construction company, digging sewer ditches. I was a union labor contractor earning very good wages in the 1970s. There was one thing I had failed to consider, however: The Vietnam War was in full swing. By dropping out of college, I had relinquished my valuable 2-S student deferment.

The U.S. Congress had enacted a draft using a lottery system that was determined by birth date. My birth date came up “lucky” 7, placing me very high on the list of men who would be drafted. I was called in for a physical exam. For reasons only the Army can understand, they rejected me for physical reasons, despite my occupation as a laborer.

In January 1971, after working for a year, I returned to Vanderbilt as a second-semester freshman. I traded the red bricks of Reinke Hall for the red bricks of Carmichael Tower 3. My grades increased significantly from my first-semester debacle. I had returned to Vanderbilt and had succeeded, erasing all questions from my mind as to whether I had the academic mettle to survive and succeed. One thing was certain: I was not interested in returning to dig sewer ditches. If I wanted to do anything in life, it was going to be through education and hard work.

I remained in school for two more years. Then I ran out of money again. In August 1973, I “dropped out” of school once more, this time finding work driving a forklift truck at the place where Dad’s last breath was drawn, the Electro-Motive Division of GM. The company had a huge order from Amtrak for 180 diesel locomotives in one year, which meant unlimited overtime. I would work 15 to 18 hours per day for 13 days in a row and be mandated by law to take a day off. With all that overtime, I was making an enormous salary.

I saved everything with two thoughts on my mind: I had met a girl named Debbie Schmidt and was intent on marrying her. She came from a humble home that couldn’t afford to pay for her to marry me, so I needed money to pay for everything. And I longed to return to Vanderbilt and finish my undergraduate degree.

I missed out on the graduation of my Reinke Hall freshmen buddies during the centennial anniversary of Vanderbilt in 1973, but in August 1974, I came back to finish my last three semesters.

By then I was married and extremely poor. My new wife worked as a fourth-grade teacher in Ashland City, Tenn., and we lived off campus. It was one of the happiest years of my life. Despite missing my dad, many good things had happened. I was married to the girl of my dreams, and I finally got to finish what I had started six years earlier in the parking lot, looking at the back of Dad’s head as he pulled onto West End Avenue.

After Vanderbilt, I continued my educational pursuits. As a 36-year-old married father of two—and working full time as a deputy director for the DuPage County Probation Department in Wheaton, Ill.—I returned to law school as a night student and graduated in four years.

Today I teach at Benedictine University, practice law, have a consulting company that assists probation departments in Illinois, and I run and do some writing. On the occasion of my 2007 retirement from the probation department after 32 years, I spoke about my work history and pulled the pocket watch from my breast pocket. I called my son, David, to the front of the room and told my dad’s pocket-watch story.

“It has guided me well,” I said. “Please remember this is your heritage.” I handed the watch to my son in front of 250 well-wishers. It is now perched on David’s mantel in Nashville, where he lives with his wife, Maggie.

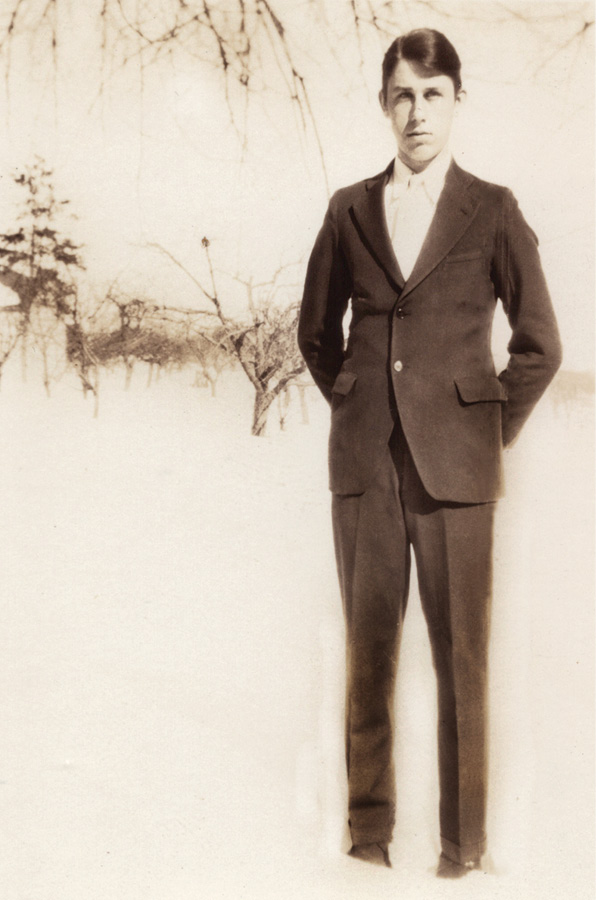

I reflect on my dad a lot. He was a large man, and when he walked into a room, his size and bearing demanded attention. He was known as a person of few words, but when he spoke you listened. He tended to be intense, but with a soft, humorous side. Dad worked three jobs at one time while also building the house I grew up in, from scratch, himself. He was a dedicated family man, for both his nuclear and extended family; he was definitely the family patriarch. Dad was a former farmer who loved the outdoors and being one with nature. I fondly remember our walks through the woods with him as kids while he identified every flora and fauna.

Dad’s one abiding trait was that he was an incessant reader and lifelong learner. He was dedicated to educating himself despite the missed opportunity to go to college on a scholarship. In his mind it was clear: His kids were going to attain the education he had missed out on.

One final footnote: In 2008, I watched my daughter, Amy DeLair, walk across the stage and graduate magna cum laude—with her bachelor’s degree in human and organizational development—from the same university from which I had finally graduated in August 1975. As I sat there my grandfather’s words to my dad echoed through my head: “With hard work you can accomplish anything.” I couldn’t help but wonder if Dad would have been as proud of me as I was of Amy that fine day, surrounded by the red bricks of Vanderbilt’s campus.