Cougars may have survived the mass extinction that took place about 12,000 years ago because they were not particular about what they ate, unlike their more finicky cousins–the saber-tooth cat and American lion. Both perished along with the woolly mammoth and many of the other supersized mammals that walked the Earth during the late Pleistocene.

That is the conclusion of a new analysis of the microscopic wear marks on the teeth of cougars, saber-tooth cats and American lions described in the April 23 issue of the journal Biology Letters.

“Before the Late Pleistocene extinction, six species of large cats roamed the plains and forests of North America. Only two – the cougar and jaguar – survived. The goal of our study was to examine the possibility that dietary factors can explain the cougar’s survival,” said Larisa R.G. DeSantis, assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences at Vanderbilt University, who co-authored the study with Ryan Haupt at the University of Wyoming.

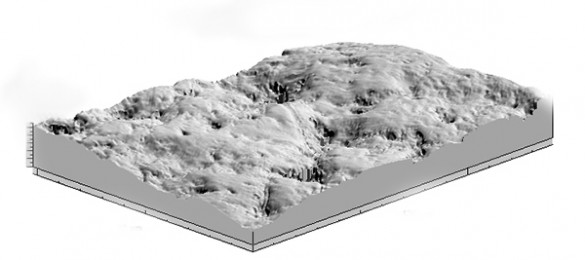

For their investigation, DeSantis and Haupt employed a new technique called dental microwear texture analysis. DMTA uses a confocal microscope to produce a three-dimensional image of the surface of a tooth. The image is then analyzed for microscopic wear patterns. The analysis of the teeth of modern carnivores, including hyenas, cheetahs and lions has established that the meals an animal consumes during the last few weeks of its life leave telltale marks. Chowing down on red meat, for example, produces small parallel scratches while chomping on bones adds larger, deeper pits.

The researchers analyzed the teeth of 50 fossil and modern cougars, and compared them with the teeth of saber-tooth cats and American lions excavated from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles and the teeth of modern African carnivores including cheetahs, lions and hyenas.

Previously, DeSantis and others found that the dental wear patterns of the extinct American lions closely resembled those of modern cheetahs, which are extremely finicky eaters that mostly consume tender meat and rarely gnaw on bones. Saber-tooth cats were instead similar to African lions and chewed on both flesh and bone.

Among the La Brea cougars, the researchers found significantly greater variation between individuals than they did in the other large cats, including saber-toothed cats. Some of the cougars show wear patterns similar to those of the finicky eaters but on others they found wear patterns closer to those of modern hyenas, which consume almost the entire body of their prey, bones included.

“This suggests that the Pleistocene cougars had a ‘more generalized’ dietary behavior,” DeSantis said. “Specifically, they likely killed and often fully consumed their prey, more so than the large cats that went extinct.” This is consistent with the dietary behavior and dental wear patterns of modern cougars, which are opportunistic predators and scavengers of abandoned carrion and fully consume the carcasses of small and medium-sized prey, a “variable dietary behavior that may have actually been a key to their survival.”

The research was supported by National Science Foundation grant EAR1053839.