Encouraging Words

The iPad you use to check email and watch Mad Men episodes may hold the key to enabling children with autism spectrum disorders to express themselves through speech. New research indicates that children with autism who are minimally verbal can learn to speak later than previously thought, and iPads are playing an increasing role in making that happen.

In a study funded by Autism Speaks, Peabody College researcher Ann Kaiser found that using speech-generating devices to encourage children ages 5 to 8 to develop speaking skills resulted in the subjects developing considerably more spoken words compared to other interventions. All children in the study learned new spoken words, and several learned to produce short sentences as they moved through the training.

“For some parents, it was the first time they’d been able to converse with their children,” says Kaiser, the Dr. Susan Gray Professor of Special Education. “With the onset of iPads, that kind of communication may become possible for greater numbers of children with autism and their families.”

The reason speech-generating devices like the iPad are effective in promoting language development is simple. “When we say a word, it sounds a little different every time, and words blend together and take on slightly different acoustic characteristics in different contexts,” Kaiser explains. “Every time the iPad says a word, it sounds exactly the same, which is important for children with autism, who generally need things to be as consistent as possible.”

As many as a third of children with autism have mastery of only a few words by the time they are school age. Previously, researchers thought that if children with autism had not begun to speak by age 5 or 6, they were unlikely to acquire spoken language. But Kaiser is encouraged by study results and believes that her iPad studies may help change that notion.

Learn more about this and other Vanderbilt early communication intervention projects.

Oldie but Goodie

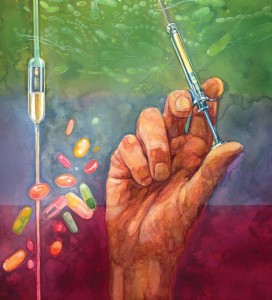

Children hospitalized for pneumonia have similar outcomes, including length of stay and costs, regardless of whether they are treated with “big gun” antibiotics such as ceftriaxone or cefotaxime or more narrowly focused antibiotics such as ampicillin or penicillin, according to a Vanderbilt study published in Pediatrics.

The findings are important because pneumonia is one of the most common reasons for hospitalization among U.S. children, the study authors say, and because broad-spectrum antibiotics are frequently overprescribed, leading to antibiotic resistance.

“Sometimes there is a perception, not restricted to pneumonia, that the use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, a ‘big gun,’ is going to be the best treatment for all patients. This perception can complicate the selection of antibiotics, especially when there is limited information to support the decision,” says senior author Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva, MPH’06, assistant professor of health policy. “To help inform those decisions, this study compared two pneumonia treatment regimens, a big gun (broad-spectrum antibiotics) vs. a small gun (narrow-spectrum antibiotics), and found no significant differences in clinical outcomes or associated costs.”

Using data from 43 U.S. children’s hospitals, the authors compared outcomes among children hospitalized for pneumonia between 2005 and 2011, receiving either ampicillin or penicillin (narrow spectrum) or a third-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, broad spectrum). According to guidelines of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, both treatment strategies are effective for disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most common bacterial cause of pneumonia.

Reinventing the Patent

It’s time to drop the requirement that inventions be “useful” in order to merit a patent, says Sean B. Seymore. A better criterion nowadays would be that an invention gets a “useful disclosure,” meaning it is explained clearly enough that others can build on it, according to the professor of law and Enterprise Scholar at Vanderbilt, who holds a secondary appointment as a professor of chemistry.

A patent gives an inventor exclusive use of his or her invention for a period of time in exchange for public disclosure of the invention. “A key challenge for the post-World War II patent system is how to assess utility for chemical and pharmaceutical inventions,” Seymore writes in “Making Patents Useful,” to be published this year in the Minnesota Law Review. “For those inventions with a known therapeutic activity at the time of patenting, the asserted utility was always clear—to treat some specific ailment or disease.

“But what about the much broader universe of chemical compounds which have no therapeutic or other concrete, nonresearch-based use at the time patent protection is sought? The judicial response to this question—the essential utility question of the modern era—has shaped the current utility requirement.”

Instead of emphasizing usefulness, Seymore suggests, the Patent Office and courts should value disclosure of the “technical details about the invention.” Dropping utility as a patentability requirement would be a radical step; it’s been part of the law since the Patent Act of 1790.