You Snooze, You Win

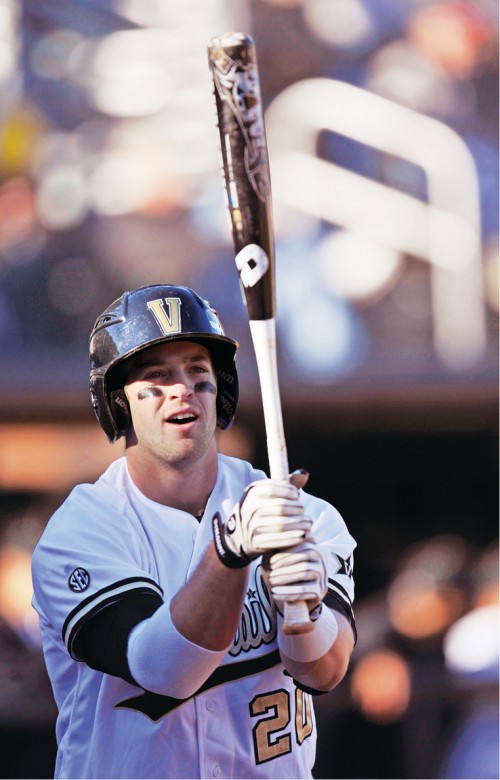

Strike-zone judgment grows worse over the course of a major league baseball season in a predictable way, possibly due to effects of grueling travel schedules, disrupted sleep patterns and fatigue, says a Vanderbilt sleep researcher.

Dr. Scott Kutscher, assistant professor of neurology, and colleagues used a database of every pitch in every major league game in 2012 to follow up on earlier studies of fatigue on players’ performance. The findings were published in the online supplement of the journal Sleep and were presented in June at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies in Baltimore.

“Once again in 2012, performance in strike-zone judgment was significantly worse at the end of the season, suggesting worsening vigilance and possible fatigue effect,” the researchers wrote.

Kutscher, who grew up in New York rooting for Derek Jeter and the Yankees, says the lessons of the research on performance could be used to give teams an advantage over a long baseball season.

“Athletes take great care in what they eat and how they exercise to help with performance, and it makes sense for sleep to be included with those activities,” he says. “It seems only natural that teams start to use sleep experts to maximize on-field performance.”

And the lessons learned by studying baseball players can apply to everybody, “whether they are trying to improve their golf swing or work productivity, or simply hoping to feel more rested,” he says. Most people need about eight hours of sleep per night to feel at their best.

“You don’t need to be standing in the batter’s box against a 95-mile-per-hour fastball to understand the limitations feeling sleepy has on your ability to perform and the measures you can take to help improve your sleep.”

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Maybe It’s Not Dyslexia

A common reading disorder goes undiagnosed until it becomes problematic, according to research at Peabody College of education and human development in collaboration with the Kennedy Krieger Institute, an affiliate of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Results of the study were recently published online by the National Institutes of Health.

Dyslexia, in which a child confuses letters and struggles with sounding out words, has been the focus of much research. But that’s not the case with the lesser-known disorder Specific Reading Comprehension Deficits, or S-RCD, in which a child reads successfully but does not sufficiently comprehend the meaning of words, says lead investigator Laurie Cutting, the Patricia and Rodes Hart Chair at Peabody and associate professor of special education and pediatrics.

“S-RCD is like this: I can read Spanish because I know what sounds the letters make and how the words are pronounced, but I couldn’t tell you what the words actually mean,” Cutting says. “When a child is a good reader, it’s assumed their comprehension is on track. But 3 percent to 10 percent of those children don’t understand most of what they’re reading. By the time the problem is recognized, often closer to third or fourth grade, the disorder is disrupting their learning process.”

Neuroimaging has shown that brain function of those with S-RCD while reading is quite different from those with dyslexia. Those with dyslexia exhibited abnormalities in a specific region in the occipital-temporal cortex, a part of the brain associated with successfully recognizing words on a page. But those with S-RCD did not show abnormalities in this region, instead showing specific abnormalities in regions typically associated with memory.

Read more about S-RCD research.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Here’s Where Things Turn Ugly

It turns out that the uglier a flower or weed is, the more allergy-inducing its pollen tends to be. Ragweed, mugwort, plantain and pigweed have more than just unsightly appearance in common—they’re some of the worst offenders to allergy sufferers, says Dr. Robert Valet, MD’05, assistant professor of medicine and an allergist at Vanderbilt’s Asthma, Sinus and Allergy Program (ASAP) clinic.

“The relationship between allergy-causing pollens and their flowers is something like a beauty pageant,” Valet says. “A general rule of thumb is that flowers that smell or look pretty attract insect pollinators, so they are not generally important allergens because their pollen is not airborne. However, those that are very ugly or plain are meant to disperse pollen in the wind, which is the route most important for allergy.”

Early spring is typically tree season, with common allergens including oak, maple, walnut, pecan and hickory. Valet says many people are concerned about fragrant and flowering trees like the Bradford pear and crabapple—but they are not typically allergens as they rely on insects instead of the wind to carry their pollen.

Grasses pick up their pollen production in late spring and early summer. In late summer and fall, common weed allergens include ragweed, lamb’s quarter, pigweed, English plantain and mugwort.

Learn more about the Vanderbilt Asthma, Sinus and Allergy Program.