The invitation from Reflector editor Joan Brasher was cordial and intriguing: “We’d love to have you write an article about how undergraduate teaching has changed over the years during your tenure.”

“Yes!” I thought, “This could be really interesting!”

I have very much enjoyed these years at Peabody, especially when teaching my undergraduate and graduate students, conducting research and working with colleagues from Peabody and across the university.

Much has changed in my 40 years of undergraduate teaching. A small sample includes: notable advances in theoretical and empirical work at the foundation of teaching; developments in the techniques and tools we use to enhance and enrich teaching; the increasing diversity that undergraduates have brought to their work with us; our students’ growing participation in local and international service learning; and more undergraduate participation in faculty research.

Just as important is what has not changed—the core values within Peabody College that have played a consistent and critical role in enabling excellent teaching and engaged student learning.

So on to the question, “What has changed?”

The merger

I joined Peabody in 1973, delighted to be part of a college with nearly two centuries of history, a home to undergraduate and graduate programs in education, special education and liberal arts and sciences, as well as an undergraduate population, many of whom were focused on preparing for careers in education.

A few years after my arrival, rumors that Peabody was experiencing financial difficulties were confirmed when it was announced that Peabody would merge with its larger neighbor, Vanderbilt University. We faced at least two new realities: we would become one of Vanderbilt’s (somewhat) independent constituent schools, and Peabody’s academic departments that “duplicated” departments in Vanderbilt’s College of Arts & Science would be disbanded. In short order, Peabody was reduced from 14 to just four academic departments. My department, Psychology, was required to drop its undergraduate major but allowed to continue its graduate programs.

The closing of undergraduate majors created concerns, primary among them worries about the financial viability of the college given the likelihood of reduced enrollment and the coming (significant) increase in Peabody undergraduates’ tuition rate. Vanderbilt’s financial structure at the time was grounded in the assumption that each school would generate, largely through tuition, revenue sufficient to cover most of its expenses. Creating new and attractive programs and majors focused on education and human development would be essential for Peabody to sustain itself.

One of the first new programs, a major in Human Development (soon renamed Human and Organizational Development), quickly became so successful that a new department was created to house it. Several HOD classes were filling our largest Peabody classroom (seating about 115 students).

Diversity and growth

Faculty across departments also developed new undergraduate majors in Child Development and Cognitive Studies. Peabody’s relatively swift success in adding excellent new programs for undergraduate, professional and graduate students, as well as the college’s emphasis on excellent undergraduate teaching, contributed to a resurgence in Peabody’s undergraduate student population.

The faculty had long prized offering relatively small classes, within which professors could come to know students, and students could ask questions, offer observations, and address important issues. To retain the learning benefits of small classes, faculty members reaffirmed team teaching as an optional strategy for use in large courses. The presenting professor handled lecture material and questions; the other team member also answered questions and offered observations, while using “unoccupied” class time to focus on learning students’ names. The students benefitted greatly from having two different (and generally engaging!) professors, with ready access to each of them as well as the teaching assistants.

Another great benefit of HOD—one that in many ways set a model for the college and university as a whole—was the emergence of The Posse Program, a scholarship program for highly capable students from generally lower-income neighborhoods in New York City.

The first group of these diverse and talented students came to Peabody in the late 1980s. I remember leaving our lecture hall one fall morning soon after our first five Posse students’ arrival. We watched as they stepped up on a concrete bench outside of Hobbs to respond to many friendly and excited questions about New York (New Yorkers were still far from common on campus), the Posse Program itself, and, perhaps inevitably, urban fashions.

One of those first Posse students, Shirley Collado, recently returned to Nashville for a short visit. Since graduating from Vanderbilt, she has earned her doctorate in clinical psychology from Duke University and is now dean of the college at Middlebury College, Vermont—home to one of the many Posse Program groups now in many universities across the country. Over subsequent years, the university, with the aid of generous donors, established similar undergraduate scholarship programs.

Rapid demographic changes across the country and resulting changes in education and social policy called our attention to the impact of impoverished neighborhood and community conditions on the learning and “life chances” of children growing up in these settings. We integrated emerging theory and research related to many of these developments into several of our undergraduate courses and in practicum experiences in community settings.

New methods, new tools

Another change is that advances in theoretical, empirical and applied knowledge in many of the scholarly disciplines influenced the adaptation of course content and methods. Peabody courses were strongly influenced by new knowledge and research about human development; community conditions that support more optimal human development; new strategies for teaching; and the conditions and circumstances that contribute to varied aspects of atypical child development. The result is that courses gained an increasingly rich and diverse base of information on which to draw as we continue to support effective learning and development for all.

Advances in technology, of course, have played a key role in altering and supporting education for our undergraduate students. Forty years ago, we relied for much of our teaching on textbooks, blackboards and chalk, typewriters, dittoed handouts, and periodic forays into the library’s repository of other information. The advent of copy machines allowed us to duplicate an expanded range of scholarly materials for class.

The emergence of the computer as an essential element of academic life continues to have often remarkable influence on teaching and learning. When students write papers, they can now access large storehouses of scholarly literature and research online. Assignments in many Peabody majors now access a huge volume of potentially pertinent research and are much more solidly grounded in careful analyses of that research.

PowerPoint has enabled many faculty to lay out concise and detailed outlines of important materials in the classroom. These can be posted on university instructional support systems, offering students 24/7 access to course materials as well opportunities to post and receive responses from the instructor and other students in the course.

In addition, faculty can integrate video examples of varied concepts being studied and discussed and offer students similar benefits as they present the results of their own individual or group learning projects.

Another significant change technology has brought is that undergraduate students now may apply their learning in a remarkably expanded range of settings focused on working with children, adolescents and families in educational, developmental and other support settings, across the Nashville community, the nation (such as Alternative Spring Break) and in varied international settings.

One last and very important change, though there are certainly others, is that undergraduates increasingly can apply for and participate in faculty research labs and projects. Two-year honors research opportunities give juniors and seniors direct experience in developing research studies, and experience with research procedures and conducting hands-on research. The honors program also offers excellent opportunities for students to present their own research findings to departmental and university audiences and, in some circumstances, to regional or national scholarly conferences.

Peabody legacy lives on

I have seen many wonderful changes at Peabody during my tenure, but thankfully there are key core values that have not changed. What are the continuities that foster the effectiveness and success of undergraduate teaching at Peabody?

First is the value Peabody faculty members place on offering knowledge that is grounded in strong research and theory, and relevant to the schools, communities, and other settings where children grow and learn. This blend of the theoretical, the practical and the beneficial lies at the heart of the Peabody ethos.

Second, Peabody remains committed to knowing and responding to our students as individuals, even as we encourage them to develop the collaborative skills that will ensure their future success.

Third, Peabody continues to keep learning settings (classes, research labs, community engagement programs) relatively small so that students have ample opportunity to ask questions, ponder, experiment and learn.

Fourth, Peabody students and faculty share an altruistic desire to use knowledge and learning to make a positive difference in the lives of children, adolescents, families, schools and communities—locally, nationally and internationally.

These continuities that undergird our teaching enable Peabody faculty to transmit critically important knowledge regarding human development and effective education within the many and varied communities we serve.

The past 40 years have seen remarkable change. No doubt there is much more change to come. My strong hope is that taken together—the inevitable changes and the continuities that have served us so well for so long—will continue to nourish our graduates’ ongoing learning and work so that they may continue to use it for good in their communities and around the world.

Listen to Voices of Peabody, the Peabody Oral History Project, which features Hoover-Dempsey and other retiring professors.

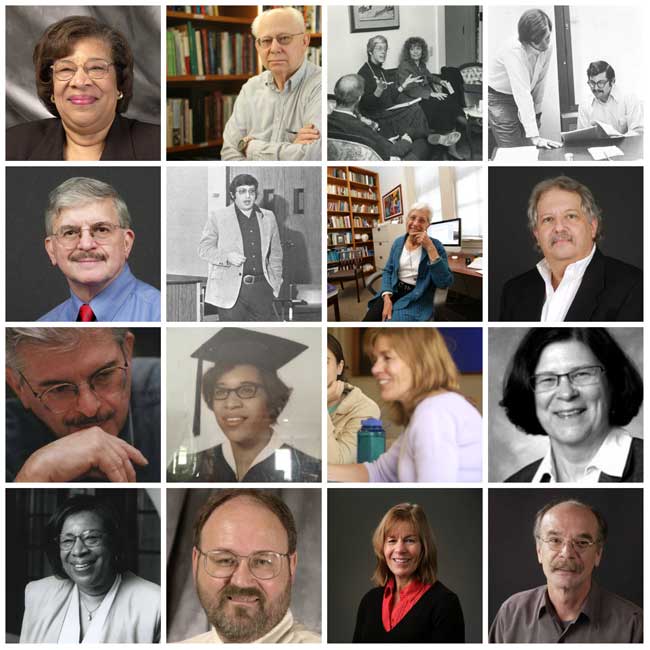

Nine professors retired from Vanderbilt this spring. They are pictured here. Can you match the name with the photo?

Special thanks to Vanderbilt University Archives and Special Collections for the vintage photos.