Research by Professor of Physics and Astronomy Keivan Stassun and postdoctoral scholar Saurav Dhital has contributed to a new theory about the formation of wide binary star systems.

Stassun explores the research in a “News and Views” column in the current issue of Nature.

Most binary stars—two stars that orbit one another—share an orbit relatively close together. But wide binary stars have huge orbits—and it’s not known why.

Stassun explains: “Stars are formed out of giant clouds of gas and dust that collapse gravitationally to eventually become a star, or, in some cases, two stars that orbit one another,” he said. “And we know how big these clouds of gas and dust—or stellar wombs, if you will—are. The biggest of them are basically about a quarter of a light year in size.”

In the case of wide binary stars, however, the orbits are much greater—as much as three light years apart in the widest instances, or roughly 10 times bigger than the typical star womb.

“[rquote]It’s very strange to have pairs of stars that presumably formed together be farther apart than the womb in which they were born,” Stassun said.[/rquote]

Stassun and Dhital have discovered thousands of these mysterious wide binaries in their research—many more than were previously thought to exist.

A leading theory to explain the wide binary phenomenon is that the two stars in these very wide binary systems were not born together, but “married” later in their lives.

”In other words, they’re not twins at all. They’re just two individual stars that were very gently gravitationally attracted to one another as they left the large cluster of stars in which they were born,” Stassun said. “I consider this a very attractive theory.”

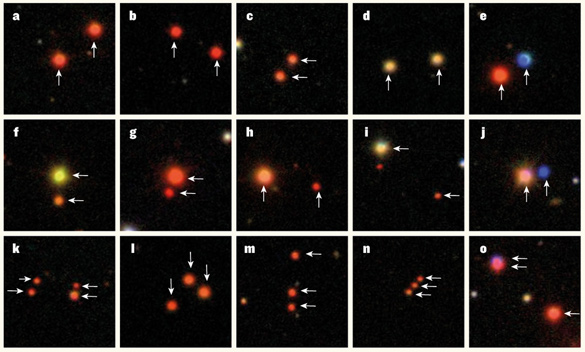

Bo Reipurth of the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Institute for Astronomy and Seppo Mikkola of Tuorla Observatory at the University of Turku, Finland, propose a whole new theory, which is the subject of their article published Dec. 5 in Nature. These astronomers describe computer simulations they conducted that show ultra-wide binary systems may be explained if they are born not as twins, but rather triplets that undergo an intricate “dance.”

The new theory proposes that three stars were formed together in very close proximity, all within a single stellar womb.

”But then over time, because there’s three stars instead of two, there’s this sort of intricate dance that the three stars undergo that brings two of the three really close together and sends the third star very far away,” Stassun said. “It just looks like two stars because two of the three are so close together that the limited imaging resolution of our telescopes makes the two close together appear as a single star.”

Stassun said further study may help support one theory on the birth of wide binaries in favor of others.

”We can study each of the wide binaries more intensively by specifically measuring the motions of what we think are two stars widely separated,” Stassun said. “If it turns out that one of the pair is actually, itself, two stars, then the star that is actually two stars will have a very erratic motion compared to the other single star.”

Read Stassun’s full column on the Nature website.

Learn more about Dhital and Stassun’s wide binaries discoveries on Dhital’s website.