Spinach power has just gotten a big boost.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at Vanderbilt University have developed a way to combine the photosynthetic protein that converts light into electrochemical energy in spinach with silicon, the material used in solar cells, in a fashion that produces substantially more electrical current than has been reported by previous “biohybrid” solar cells.

The research was reported online on Sep. 4 in the journal Advanced Materials and Vanderbilt has applied for a patent on the combination.

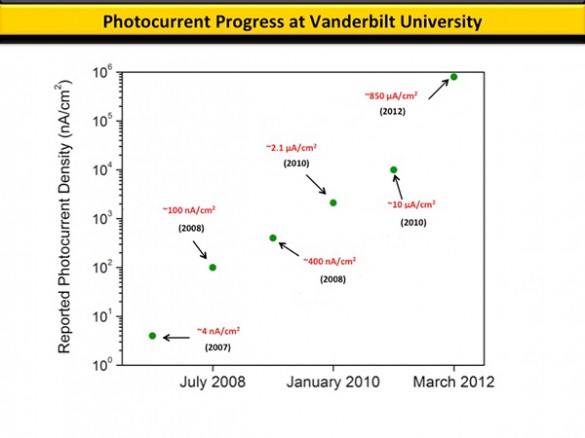

“This combination produces current levels almost 1,000 times higher than we were able to achieve by depositing the protein on various types of metals. It also produces a modest increase in voltage,” said David Cliffel, associate professor of chemistry, who collaborated on the project with Kane Jennings, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

“If we can continue on our current trajectory of increasing voltage and current levels, we could reach the range of mature solar conversion technologies in three years.”

The researchers’ next step is to build a functioning PS1-silicon solar cell using this new design. Jennings has an Environmental Protection Agency award that will allow a group of undergraduate engineering students to build the prototype. The students won the award at the National Sustainable Design Expo in April based on a solar panel that they had created using a two-year old design. With the new design, Jennings estimates that a two-foot panel could put out at least 100 milliamps at one volt – enough to power a number of different types of small electrical devices.

Harnessing the power of spinach

More than 40 years ago, scientists discovered that one of the proteins involved in photosynthesis, called Photosystem 1 (PS1), continued to function when it was extracted from plants like spinach. Then they determined PS1 converts sunlight into electrical energy with nearly 100 percent efficiency, compared to conversion efficiencies of less than 40 percent achieved by manmade devices. This prompted various research groups around the world to begin trying to use PS1 to create more efficient solar cells.

[/caption]Another potential advantage of these biohybrid cells is that they can be made from cheap and readily available materials, unlike many microelectronic devices that require rare and expensive materials like platinum or indium. Most plants use the same photosynthetic proteins as spinach. In fact, in another research project Jennings is working on a method for extracting PS1 from kudzu.

[/caption]Another potential advantage of these biohybrid cells is that they can be made from cheap and readily available materials, unlike many microelectronic devices that require rare and expensive materials like platinum or indium. Most plants use the same photosynthetic proteins as spinach. In fact, in another research project Jennings is working on a method for extracting PS1 from kudzu.

Since the initial discovery, progress has been slow but steady. Researchers have developed ways to extract PS1 efficiently from leaves. They have demonstrated that it can be made into cells that produce electrical current when exposed to sunlight. However, the amount of power that these biohybrid cells can produce per square inch has been substantially below that of commercial photovoltaic cells.

Another problem has been longevity. The performance of some early test cells deteriorated after only a few weeks. In 2010, however, the Vanderbilt team kept a PS1 cell working for nine months with no deterioration in performance.

Panel of biohybrid solar cells that Vanderbilt undergraduate engineering student entered in the National Sustainable Design Expo. (Amrutur Anilkumar/Vanderbilt University “Nature knows how to do this extremely well. In evergreen trees, for example, PS1 lasts for years,” said Cliffel. “We just have to figure out how to do it ourselves.”

Secret is “doping” silicon

The Vanderbilt researchers report that their PS1/silicon combination produces nearly a milliamp (850 microamps) of current per square centimeter at 0.3 volts. That is nearly two and a half times more current than the best level reported previously from a biohybrid cell. The reason this combo works so well is because the electrical properties of the silicon substrate have been tailored to fit those of the PS1 molecule. This is done by

implanting electrically charge atoms in the silicon to alter its electrical properties: a process called “doping.” In this case, the protein worked extremely well with silicon doped with positive charges and worked poorly with negatively doped silicon.

To make the device, the researchers extracted PS1 from spinach into an aqueous solution and poured the mixture on the surface of a p-doped silicon wafer. Then they put the wafer in a vacuum chamber in order to evaporate the water away leaving a film of protein. They found that the optimum thickness was about one micron, about 100 PS1 molecules thick.

Protein alignment

When a PS1 protein exposed to light, it absorbs the energy in the photons and uses it to free electrons and transport them to one side of the protein. That creates regions of positive charge, called holes, which move to the opposite side of the protein.

In a leaf, all the PS1 proteins are aligned. But in the protein layer on the device, individual proteins are oriented randomly. Previous modeling work indicated that this was a major problem. When the proteins are deposited on a metallic substrate, those that are oriented in one direction provide electrons that the metal collects

while those that are oriented in the opposite direction pull electrons out of the metal in order to fill the holes that they produce. As a result, they produce both positive and negative currents that cancel each other out to leave a very small net current flow.

Biochemical engineer Kane Jennings. (Daniel Dubois/Vanderbilt University) The p-doped silicon eliminates this problem because it allows electrons to flow into PS1 but will not accept them from protein. In this manner, electrons flow through the circuit in a common direction.

“This isn’t as good as protein alignment, but it is much

better than what we had before,” said Jennings.

Graduate students Gabriel LeBlanc, Gongping Chen and Evan Gizzie contributed to the study.

The research was supported by National Science Foundation grant DMR 0907619, NSF EPSCoR grant EPS 1004083 and by the Scialog Program of the Research Corporation for Scientific Advancement.